| Zeitschrift Umělec 2000/3 >> Captive of the Concept of the Miraculous (Between Art and Life) | Übersicht aller Ausgaben | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Captive of the Concept of the Miraculous (Between Art and Life)Zeitschrift Umělec 2000/301.03.2000 Miloš Vojtěchovský | performance | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

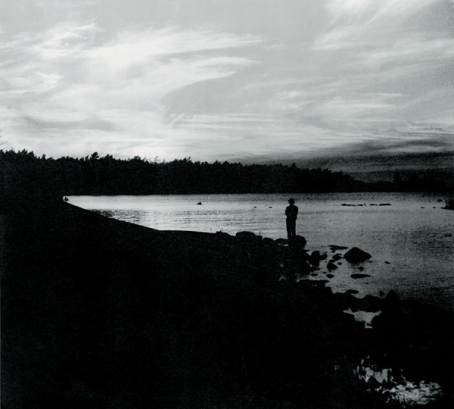

Jan Bas Ader entered art history in his final performance, which was exceptional and remarkable for two reasons. Firstly, there is no visual documentation of it (at least I have not found any). It was a peculiar and adventurous event, during the course of which Ader died at the age of 33 somewhere in the Atlantic between Europe and America. In July 1975, he set out on a small sailboat to cross the Atlantic Ocean from Cape Cod in Massachusetts to Cornwall. His final performance, which lasted a few months (titled In Search of the Miraculous), ended tragically and prosaically as the capsized sailboat emerged on the shore in Ireland six months later. Only some photographs and video documentation remained of Ader’s previous projects in which he repeatedly showed his stubborn fascination and inclination for the blurry boundary between life, art and…death. In his series entitled Fall, Ader is photographed and filmed just before falling or as he’s falling—from a tree, the roof of his bungalow in California, into a sewer in Amsterdam into which he rides his bike, as the local fashion requires. Ives Klein’s now famous “Jump” where he jumps from a wall with arms spread seems to be a mere non-committal play of the fall of Icarus, compared to Ader’s real and dangerous activities. In addition to the tragic death of such pop stars as Jimi Hendrix and Brian Jones in the 1970s, his “voluntary” disappearance (or death—searching for the transcendental Miraculous) became a symbolic completion of the romantic concept of the blending of art and life attitudes. For a long time, the death of an Artist-Idol was a caution for the more sober, ironic and calculating art of the past two decades during which the physiological phenomenon of AIDS became the new tool in artistic eschatology. Considering the many reported artistic deaths, it is surprising that there are very few links to Ader‘s journey into the unknown on the Internet.

There are also very few references to the legendary actions by Hehching Hsieh, a Taiwanese immigrant to New York, of walking the fine line between art and life. (They took place at the same time as intimate performances by Mlčoch, Miller and Štembera in Prague). He fully cultivated model experiments of time, the body, and sometimes the patience of the audience. European and North American performance and happening artists conducted the experiments. He then disappeared from the scene for a long time, withdrew himself, and refused to transfer his experiments into the index of his own career. After relocating to the USA, he stopped painting and decided to explore the scope of the contemporary “Western” concept of Art—life in the form of experiments in which he set the ascetic limits of patience, physical fatigue and spiritual concentration for himself. In 1978, under the name Sam Hsieh, he announced that he would lock himself in barred solitary confinement in his studio where he would not read, write, listen to the radio or watch TV. The only contact with the outside world would be mediated through his friend Cheng Wei Kuong who would take care of the food and clothing. The following crucible compensated for the experience of this year-long absolute solitude: in April 1980, Hsieh announced that he would stamp a card in a machine attached to a wall in his studio every hour for one year. A 16mm camera installed in the room would record one frame every hour and keep track of the changes in his face and the length of his hair and beard, which would grow undisturbed for 365 days. The next performances began on September 26, 1981. Equipped with a sleeping bag and a few necessary items, he lived in the streets of Lower Manhattan for one year without entering any interiors, not a single building, subway, train, car, plane, boat, cave or tent. Cameras documented his life in the open air (in cooperation with the Art Gallery EXIT), and it was involuntarily interrupted for one night when the homeless artist was arrested by the police and he had to spend a night in a cell. Hsieh transformed himself into an exemplary homeless person as he experienced all the social and physical constraints that thousands of his colleagues had to involuntarily deal with in the concrete jungle. In 1983, in cooperation with the performer Linda Montano, he kicked off another extreme existential predicament: a 2-meter long rope bound the two of them for a one-year sentence of sharing their lives together without touching and without privacy. As Hsieh later said, this was the hardest test of his patience he had ever experienced. His year-long purification performance in 1985 was a logical follow-up. The goal this time was to drop out of the arts—not to read about the arts, not to go to museums and galleries and to be concerned exclusively with life. On December 31, 1985, on his 36th birthday, he began his 13-year-long anti-performance during which he was involved in the arts but solely as a private personal project. He worked as a laborer and with the money made from selling his Taiwanese paintings bought a house in Brooklyn, which he gradually restored and where he established the Earth Foundation. This model social sculpture, consisting of three furnished apartments, served as an artists’ residence, where an artist could live free for one year as an asylum from the expensive and fast city. The project of concentrated work and solitude ended in 1999. Hsieh now concerns himself with documenting his work on CD-ROM, which he makes himself and which is supposed to aid him in his return to the World of Art. Linda Montano, the one Hsieh was tied to in his Houdini act, has been working on the edge of art and life since the 1970s, as was Lynn Hirshman who shut herself up in the Dante Hotel for several months in 1972. Her artistic program is defined by the following motives: Transformation, Exercises in Attention and Concentration, Hypnosis, Eating Disorders, Crossing the Boundaries Between Art and Life. In 1973, she bound the conceptual artist Tom Marioni for three days and nights. In 1975, Montano lived in a gallery without speaking for three days. In December 1984, she began her “seven years of live art,” which consisted of conducting mysterious acts such as wearing only one color, listening to the sound of one note for seven hours a day, speaking with a different accent every year, reading palms and consulting the public once a month in New York’s New Museum. In 1991, she continued the “seven years of live art” project (1991-1997) and established The Art/Life Institute in Kingston where she is involved in similar disciplines accompanied by some sort of mysterious astral dimension. Further information can be obtained for 10 dollars sent to: Linda Montano, The Art/Life Institute, 185 Abeel Street, tel. (914) 338-2813. The ideal of authenticity and counter-culture appears romantic from the perspective of recent Western visual arts, and most attempts at sampling life and art seem to be small-minded and sometimes forced, even untrustworthy. The increasing media attention and commercialization of post-modernism leads to a statement that “Art is Artificiality and Life is Life,” or “Art is Business and Life is Game.” In the meantime, the mass media were flooded with sincerity, authenticity and the miraculous, all packaged in soap operas, sci-fi Hollywood idylls, web pornography-tempered chats and New Age shamanistic instructions for easy, guaranteed and cheap tickets to the realm of the transcendent. The more sophisticated the process of artifact production, the more distant from the depth of the inner personality of an artist and his/her own psyche, the more attractive it is for contemporary high art and more accessible it is to an unassuming, entertained, statistically monitored audience and the automated patterns of consumer behavior of the art industry. The New York artist Roxy Paine sensitively responded to this transformation by building sophisticated vending machines for the production of paintings and sculptures, which were perfect esthetic and synthetic products of computer algorithms. His careful replicas of magic mushroom fields and samples of fragile poppy seed plants symbolize the other side of the mysterious origins of the artificial object. Mauricio Catallan dealt with the funny metaphor and banter of the Miraculous and Mysterious in a grotesque manner: in the middle of a gallery, standing still, is a life-sized elephant; it is covered with a white veil with only the glass animal eyes peeping out from under. The digital magician Perry Hoberman dealt with the industrialized Miraculous of the fin de siècle as an on-going, changing installation, as he transformed the archetypal magic cave into a shop. Various electrical appliances collected in second-hand shops or found on streets constituted a chaotic, blinking, noisy electric and electronic assemblage, brought to life by sensors and switches, activated by viewers stepping past. The technical “secondary” reality appears as a theme in several drawings by Mark Lombardi which were exhibited at a big presentation of contemporary New York art entitled Greater New York in PS1. In an accompanying text, Lombardi describes them as “narrative structures.” Given the number of presented artifacts of everything spanning from a video documentation of the ritualistic tattooing of one’s own body to the digitized metaphysics of staring into empty space (Angles Dust), Lombardi’s works were striking with their soberly positivist accuracy and conceptual context. Each of these structural drawings represents a record of the movement of shares on the stock exchange, following the process of the bankruptcy of a multinational bank, syndicate or corporation. The mapping out of technical and functional relationships and the allocation of power in a political, economic and social structure, where visual art (seemingly) has no place, was unaffectedly presented in an environment of artistic production (unlike Hans Haacke’s latest installation at the Whitney Biennial). After a careful study of data and information accessible in the media, a web of real and potentially tragic events in life begins to surface, influencing thousands of people’s lives in various parts of the world. Most of us depend on the incalculable, hermetic flow of the multinational trade of goods and money. Lombardi’s drawings reflect the statistical model of an event, limited by time, not as a personal interpretation of an artist or a subjective esthetic metaphor of a situation, but as a sober, careful diary entry of an observer who is aware that he is one of the vector lines in the organism of his own drawing. The drawings are esthetically elegant but ultimately just as disturbing as photographic images from the Balkan wars. They document the route of the journey Western art has traveled over the past 30 years—a shift from the romantic act of a symbolic personal sacrifice to the vain attempts at the Miracle of incorporating Art and Life and the cold-blooded description of one struggle, the profane horror of economic predestination from which it is difficult to escape. (Mark Lombardi hanged himself in his studio in April, and, like Jan Bas Ader, he didn’t leave documentation of his final act.)

01.03.2000

Empfohlene Artikel

|

|||||||||||||

|

04.02.2020 10:17

Letošní 50. ročník Art Basel přilákal celkem 93 000 návštěvníků a sběratelů z 80 zemí světa. 290 prémiových galerií představilo umělecká díla od počátku 20. století až po současnost. Hlavní sektor přehlídky, tradičně v prvním patře výstavního prostoru, představil 232 předních galerií z celého světa nabízející umění nejvyšší kvality. Veletrh ukázal vzestupný trend prodeje prostřednictvím galerií jak soukromým sbírkám, tak i institucím. Kromě hlavního veletrhu stály za návštěvu i ty přidružené: Volta, Liste a Photo Basel, k tomu doprovodné programy a výstavy v místních institucích, které kvalitou daleko přesahují hranice města tj. Kunsthalle Basel, Kunstmuseum, Tinguely muzeum nebo Fondation Beyeler.

|

New book by I.M.Jirous in English at our online bookshop.

New book by I.M.Jirous in English at our online bookshop.

Kommentar

Der Artikel ist bisher nicht kommentiert wordenNeuen Kommentar einfügen