| Umělec magazine 2003/2 >> Tehching Hsieh – One Life Performance | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Tehching Hsieh – One Life PerformanceUmělec magazine 2003/201.02.2003 Jan Suk | performance | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

Performing the Self

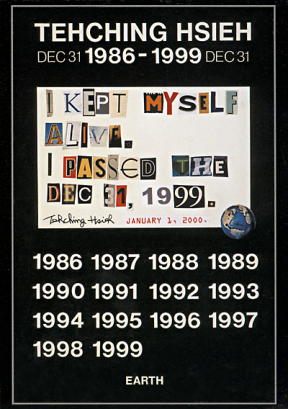

When it come to challenging life values, a more compact, clear, genuine, and universal example in the field of performance art cannot be found. The work of Tehching Hsieh is a manifestation of ultimate human freedom, as solid as marble. His art deals with the most powerful elements at play in life, while at the same time touching on the most intimate subjects. Modern art has become so spread out, shattered and lost in formal dogmatism that nowadays it is present in every moment, in every possible form and idea. Performance art, being the most direct and true expression, stripping away as it does all formal restrictions, theatrical directness while being “here and now” proves, especially at these times, the truth of the most fascinating artistic discourses. The figure of Tehching, standing somewhat aside yet at the same time in the center of public attention, is a prime example of the theory that action art is the most live, direct, and influential (and maybe neglected) of all modern artistic approaches. Ridding himself of all possible physical attributes while remaining most physical, Tehching Hsieh tries to abstract himself from everything to the very basic existential forms. Such a pure and complete gesture is extremely idiosyncratic, and in the context of Czech art, can only be compared to Karel Miler’s simple Blíže k oblakům (Closer to the Clouds — 1977) and Sledování (Watching —1972), and that only with difficulty. The liberating and purifying nature of Hsieh’s work can also be traced in the action 33 by Richard Fajnor in ROXY in 1999. Yet Tehching’s gestures overstep the private and intimate character of contemporary works. His pieces burst with originality. Hsieh’s work consists of only a few performances, but they stretch over his entire life. In total, Tehching has managed to produce five one-year performances, and a longer piece. They all have in common publicly announced statements and a thoroughly elaborate set of restrictions and rules. Tehching’s artistic activity began on his arrival to America in 1978. The limited, yet universal and beautiful works will remain cornerstones of a modern understanding of performance and, perhaps, contemporary art in general. One-year performance #1: The Cage Piece Hsieh spent an entire year locked inside a cage that he had constructed in his loft. With no one to talk to, no radio, television, or books, he spent the time only with himself — just being: thinking, counting the days. Each day he documented by making a mark on the wall and taking a photograph of himself. An assistant, with whom he did not exchange words, brought him food, and disposed of waste. The first piece expresses the artist’s isolation and solitude. How much outside nourishment can we give up and still remain ourselves? Hsieh’s first work is a rich set of questions. One-year performance #2: Punch Time Clock Piece In his second piece, Tehching punched a time clock every hour on the hour twenty-four hours a day for an entire year. “To help illustrate the time process,” Hsieh shaved his head before the piece began, and then let his hair grow freely for the duration of the performance. Every time he punched the clock, a movie camera shot a single frame. The resulting time compresses each day into a second, and the whole year into about six minutes. This work represents a manifestation of the human acceptance of time. It focuses on the nature of time and the human obsession with time. We are fundamentally temporal beings. Yet we rarely pay attention to the passage of time. We tend to think of time in terms of the activities that fill it up. Or we think about time negatively, in terms having to wait. Stripping all the contents and contexts away, Tehching struggles to experience something uniquely pure. He did this by pushing to the extreme the way our society equates time with work. He used a time clock, the device that so mercilessly judges human accomplishment by the measure of time spent. The passage of time itself, devoid of any particular content, became the sole object of his labors. By pushing our society’s reification of time to its ultimate point, Hsieh was able to rediscover an inner experience of time, a sense of pure eventless duration. A universal being. One year performance #3: Outdoor Piece In this work, Hsieh stayed outside for a whole year. He did not enter any building or roofed structure. He spent the entire year roaming around New York. He relied on pay phones and chance meetings to keep in touch with his friends. Each day, he recorded his wanderings on a map, noting in particular the places where he ate or slept. The whole action is very much limited to the basic needs record — eating, sleeping, and defecating. It is almost an inversion of his first action. Hsieh opened himself up, completely, to the outside: he tested his powers of survival in circumstances that were usually beyond his own control. Without a home, one becomes almost invisible, socially uncategorized. He finally became himself, the artist — creator, throwing away all brushes and equipment just to remain alone, the true “self.” Art / Life One year performance #4: Rope piece This performance was a collaboration with Linda Montano. The two of them spent a year tied together by an 8-foot rope. At the same time, they both tried to avoid actually touching, so that they could maintain some sense of personal freedom. Hsieh and Montano did not know each other before the piece began. But once it started they were never separated for a period of one year. Each day, they kept records of their time together by taking photos and recording audiotapes. Linda Montano had also been a collaborator with Tom Marioni: before this work they did Handcuff — a performance in which she was handcuffed to Marioni for three days. The piece with Tehching explores the dimensions of intimacy. How close can (two) people get, and to what extent must they always remain strangers to one another? This piece is not about patience and suffering. On the contrary, it is all about life. As Linda says, she underwent the piece “not to waste a second. That art/life task shall become the task I have given myself until I die. To make every minute count.” One year performance #5: ---- In his last one-year piece, Hsieh just “went in life.” This last action in fact is a negation of the previous four. Hsieh spent an entire year without art: making art, talking or reading about it, viewing it, or in any other way participating in it. Since there was nothing special during this period of his life, there was nothing to record. How does art differ from ordinary life? The work is an endeavor to make art and life coincide. Life is transfigured, given a special richness and significance, by being turned into a work of art. In the words of Tehching, performance and life are connected. In Cage, it is about isolation, Outdoors was a struggle with the outside world. Being tied together is a clear idea, because to survive we are all tied up together, he feels. We struggle because everybody wants to feel freedom. Individuals are independent. The piece becomes art and life — and also a year is a symbol of things happening over and over. In other words it is a multiplying of one’s world over and over. Simply put, to break down habitual patterns. Earth This 13-year-long performance about freedom was Hsieh’s last: it took place between his 36th birthday and his 49th. Llike the fifth performance, but unlike the first four, documentation only happened after completion. When Hsieh announced the piece, he said he would make art, but only in secret: never to show it in public. He did not reveal the content or the purpose of the performance until the day after it was over. Only then did he give his report: “I kept myself alive,” he said, and made it through to the new millennium. In this piece, Tehching reconfigured the relationship between art and life. Hsieh’s pieces all suggest that through their repetition, and their absorption into daily routine, these tasks become as ordinary as anything else. And that is perhaps the most important transformation of all. This last acclaimed 13-year-old “piece” proved his discipline. Most people exist in this last stage. They create, but don’t show it to the outside wold. Universal threat or blessing at the same time. Tehching becomes a beautiful example for those who do not dare speak out loud or show off. At the same time, his works demonstrate how magical, beautiful and difficult the life of some of us truly is. Tehching is the most universal artist I can think of. One Life Performance But nothing ever works out entirely as planned. Thus, during the second performance, Hsieh overslept and missed a small number of clock punches. During the third performance he was compelled to stay a few hours indoors when he was arrested after getting into a fight. During the fourth piece, he and Montano touched each other a few times by accident. And this is probably the most important realization in Hsieh’s work: the space between — recovery time — the short time spent between each piece. This reveals his weakness, his truly existential need to take a rest: that the pieces are primarily not his life only. But that his life and actions represent the most deferred dreams that people have — to turn life into an absolutely artistic form. A certain confluence, or, in other words, a symbiosis. In a letter to me, Tehching Hsieh explains that “my works could be named as performance art or action art, and live art is also OK. Mostly the performance art works are happened in a stage but to me, the life is my stage so I prefer to leave this question to the historian[s] and art critic[s], I believe their answer would be better than mine. I have a lot of pleasure [doing] my work. I do not think I want [to] suffer for no reason. The piece and also TH art is about being like an animal, naked. We cannot hide our negative sides. We cannot be shy. It is more than just honesty — we show our weaknesses. It represents the umbilical cord visible. When we die it ends. Until then we are all tied up.” Tehching’s constant testing, his challenging not the physical possibilities, but social patterns is another key to his explanation. A one-word definition for such a life-long quest might be: freedom. However, in the search for his true self, Hsieh forces us to call this approach a different, less artistic term: mutiny. Tehching Hsieh not only questions our own values, he is unveiling for us a real treasure, a self-reflective look.

01.02.2003

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment