| Revista Umělec 2005/1 >> "Houston, We Have a Problem" | Lista de todas las ediciones | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

"Houston, We Have a Problem"Revista Umělec 2005/101.01.2005 Theopisti Stylianou | Teoría | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

Bringing celestialart philosophy production down to the earthly sphere of adult art education

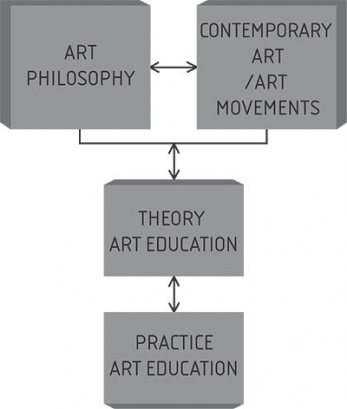

Is art philosophy a distant, blinking star in the sky of art education or a shining sun? As a practicing adult art educator I can assure you that the transition from art philosophy to art education practice is not that easy. With this article I attempt to explain why this is the case by demonstrating how art philosophy influences art education theory, and then, by discussing the challenges of working with adults with different needs and expectations. Art Philosophy and Art Education Theory Art philosophy and contemporary art are engaged in a quite complex and dynamic two-way interaction. We observe that when one changes, the other follows. Not surprisingly, art education theory is also part of this dynamic and must adjust itself to match the contemporary philosophy and art movements. Ideally, this adjustment has an equal effect on art education practice (see figure 1). A good example is the 1950s in the United States. The predominant art movement was Abstract Expressionism. The predominant art theory/philosophy was Formalism with its main supporters being the art philosopher Clive Bell and art critic Clement Greenberg. Bell (1914) believed that: “In each [artwork], lines and colors combined in a particular way, certain forms and relations of forms, stir our aesthetic emotions. These relations and combinations of lines and colours, these aesthetically moving forms, I call Significant Form”. Bell (1914) also believed that “to appreciate a work of art we need [to] bring with us nothing from life, no knowledge of its ideas and affairs, no familiarity with its emotions.” And art education followed in abstract expressionism and Formalism’s footsteps insofar as schools and art academies encouraged students to focus on colors and forms, express emotions in an abstract way, liberate themselves from subject matter and get closer to the physicality of the canvas and the paint. In the 1960s, movements like pop art, minimal art, and conceptual art widened the gap between art education and professional art. Students were still wrestling with the concept of expression through color and form or with the traditional problems of representation (Haanstra, 1999). In terms of art philosophy, the dominant theory since the 1960s, still not fully discredited, is Arthur Danto and George Dickie’s Institutional Theory. Danto (1964) believes that “to see something as art requires something the eye cannot decry—an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: An Artworld.” To appreciate an artwork, in other words, its forms, colors, and lines are not enough. Without the knowledge of the theoretical and historical background of the artwork, an “innocent” eye cannot fully grasp the importance of the work. Because of these changes, art education theory needed to adjust itself to contemporary art movements and philosophy and it did. As a response to the ideas set forth by the Institutional Theory and contemporary art, for the past few years the American Art Education Association has been encouraging the use of Discipline Based Art Education (DBAE). According to DBAE, a four-part system designed to enhance and complement traditional art education, art production must be complemented by art history, art criticism, and aesthetics. Some European countries have, to some extent, also been applying a more holistic approach to art education by devoting more time to art analysis and history (Haanstra, 1999). Therefore, the current leading philosophical and art education theories expect students to be able to analyze, interpret, and produce in a contemporary art framework. Seen in this light, then, the main goal of art educators today is developing visual and interpretive skills hand-in-hand with technical ones. But can we, as practicing art educators, reach this goal when we are dealing with adults with different needs and expectations? Adult Art Education Practice In reality, it is not always easy to reconcile theory and practice. Working as an adult art educator, Danto’s Artworld seems far away - at least further away than practical issues that may (and did) arise. For the past two and a half years I have been teaching drawing and painting in perhaps the only adult art education center in Prague that offers these classes in English. My students come from all over the world – Sweden, Holland, Ireland, UK, Germany, Spain, France, United States, Korea, Czech Republic etc. – and this creates a diverse and dynamic class environment. I was curious about why adults suddenly decide to pick up pencils and brushes and engage themselves – many of them for the first time in their lives – in creative pursuits. Intrigued by this, I had my students answer a brief questionnaire at the beginning of each 8 or 11-week course, which included the question, “Why do you take this course?” The results of the questionnaire and insights I gained from informal conversations were quite surprising. Goal-oriented VS Activity-oriented learners Borrowing Houle’s (1961) terminology, there are three types of adult learners: the goal-oriented, the activity-oriented, and the learning-oriented. The majority of participants in my classes fall into the first two categories. In the following paragraphs I define both goal-oriented and activity-oriented categories and show how my students fit into them. Meanwhile, the reader should keep in mind that often people are both goal- and process-oriented, but they usually tend to be more one than the other. Goal-oriented adult learners: Goal-oriented students are “those who use education as a means of accomplishing fairly cut objectives” (Houle, 1961). Characteristic questionnaire answers I received that fall into this category are: “[I took this course in order] to develop my drawing skills. I’m interested especially in introducing shadow, proportion and trying other mediums since I only use pencils.” “I’d like to improve my drawing skills. I’m building a portfolio for studies in fashion and costume design. I’d like to improve my compositional skills and learn about color as well.” People that are goal-oriented have a specific goal that they want to achieve by the end of the course. Activity-oriented adult learners: Activity-oriented students are “those who take part because they find in the circumstances of learning a meaning which has no necessary connection, and often no connection at all, with the content or announced purposes of the activity” (Houle, 1961). I was surprised to find out how many participants mentioned activity-oriented motives for taking the course. Some questionnaire answers that fall into this category are: “It’s a very good way to meet other people – Czechs as well as expats, It makes a welcome change from teaching English during the day.” “What I love about it is that when you are working on something (painting), you are so fully concentrated that you forget the rest of the world for a while.” “I look after my son and never have the time to sit down and draw so this gives me the opportunity to get something started.” “It gives me peace and it’s rewarding.” Some social reasons like meeting new people were expected. However, from informal conversations with students, I realized that some of their reasons go even deeper. One initially puzzling observation was that the majority of my students were women, who represented at least 75% of each of my classes. Many of them were young mothers or were pregnant and very often fell into the process-oriented category. In some cases, two friends would join the class as their night out together without husbands and children. Their goal was usually to enjoy the evening, meet new people, and at the same time learn something new. Another example of an activity-oriented situation is a couple I once had - a busy businessman and his pregnant wife who joined the course in order to spend some quality time together. As an art educator, it’s one thing to be responsible for teaching basic art techniques and another to be responsible for someone’s only night out or a couple’s quality time together! Previous research also supports these findings since it shows that people often take art courses for social and “therapeutic” reasons as much as educational ones. Buell (1996), a music appreciation instructor, indicated that two thirds of his class “took the course for what can best be described as therapeutic reasons, to help cope with personal or family-related stress ranging from mild social anxieties to grief therapy.” In addition, offering art courses for specific target groups like women is not something new. Feminist artists-educators are offering art courses that are designed to meet the challenges that women face nowadays (Clover, 2001). Is art analysis and history a waste of time? According to Haanstra (1999), most of the art course participants “…come to learn to paint and not to learn to analyze art. In their view, the time devoted to art analysis and art history is more or less a waste of time.” It is true that none of my students stated that his/her main reason for taking the course was to better understand the professional art world, and I’m sure that many students would agree with the above statement. In general, people are satisfied if they can learn some basic skills and techniques, enjoy the process, and meet new people. This is, of course, consistent with their personal goals. Consequently, a number of students resist the introduction of art history, criticism, and aesthetics. As a result of this attitude, they also resist the creation of art courses consistent with contemporary art philosophy that emphasize the development of visual and interpretive skills. The big dilemma Keeping in mind that many adult learners take art courses to satisfy a need which may not be primarily educational -- it may be social or emotional -- we face the following dilemma: Do we focus on high quality courses that make art philosophy and educational theory the guiding light, partially ignoring our students’ needs? Or, do we primarily focus on students’ needs and, as a result, reduce philosophy to a distant and unapproachable star? It is indeed a difficult decision. References: Buell, T., (1995), The Therapeutic Function of Adult Education in the Arts. In J. David, B. McConnell , & G. Normie (Eds.), One World, Many Cultures: Papers from the international Conference on Adult Education and the Arts (pp. 50-56). Scotland: St. Andrews. Clover, D. E., (2001). Feminist Artist-Educators and Community Revitalization: Case Studies from Toronto. CASAE-ACNNA National Conference 2001, Twentieth Anniversary Proceedings. Retrieved November, 2004, from http://www.oise.utoronto.ca/CASAE/ cnf2001/clover.pdf Danto, A., (1964). The Artworld. The Journal of Philosophy, LXI, 571-584 Dickie, G., ( 1969). The Institutional Conception of Art, 7-19 Haanstra, H. F., (1999), The Dutch Experiment in Developing Adult Creativity. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 81, 37-45. Houle, C. O., (1961). The Inquiring Mind. Madison, Wisc.: University of Wisconsin Press.

01.01.2005

Artículos recomendados

|

|||||||||||||

Comentarios

Actualmente no hay comentariosAgregar nuevo comentario