| Zeitschrift Umělec 2003/2 >> If I Want to Write a Review, Then I’ll Write It | Übersicht aller Ausgaben | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

If I Want to Write a Review, Then I’ll Write ItZeitschrift Umělec 2003/201.02.2003 Marek Pokorný | geschichte | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

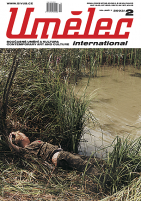

Jana Kalinová: When I don’t know, so I ask, I would ask, but I don’t know who; Home Gallery, Prague, Sept. 9 – Sept. 13, 2003

Experience tells me that in simple situations in which I don’t really know what to do, only rarely — as a typical representative of the male of the species — do I choose the most effective path: in short, I don’t ask where this or that street is, what is the quickest way out of town, and I don’t ask which direction I should take. And so my wife, if she is with me, rushes out of the car after a while, runs to the first shop she sees, and stops a passer-by so that the information she is seeking — quite ordinary, banal and usually easily available without effort — is finally gained. She doesn’t underrate my abilities, but she simply doesn’t need … Certainly nothing at such moments argues against it: She beelines directly to her precisely defined goal, saving energy and time. There are more important things. However, there are situations when no one is around, when not only your partner lets you down, but that uncertainty, which she would fight against, has no foundation. The woman in this case runs to the newspaper stall: she would like to know what this is all about, but the paper seller only wags his head. It is just this sort of problem she has created for herself; the paper seller knows nothing about it, and doesn’t know who might. And if the woman turns around, her partner – if he was there at all – is long gone. The statement in the title of the exhibition by Jana Kalinová in Home Gallery could be referring directly to the situation where the uncertain and the unclear is uncertain and unclear out of principle, from its very establishment. It is uncertain and unclear quite fundamentally or temperamentally. Only her problem remains, her exhibition and… her observation, which extends out from us, out from our problems, out from her watching us and out of our unanswered questions. Without anyone accusing her, Jana Kalinová has come up with a certain (unpleasant, but completely justified) finding — art is a paradox, a question without an answer, not an answer hidden in the question, such as would please phenomenologists. And so it seems to me that she has found herself personally and artistically free in Prague (it may sound silly or haughty, but there is, from my side, a certain envy in it), then there, where everybody wants to be, but few are able to. If one of the basic characteristics of what I am thinking about is that it is still possible to allow art the ability to update something unexpectedly known, or to state something maybe a little bit on the edge, precisely and alarmingly, then from her time on the periphery, Jana Kalinová has reached this exhibition (maybe not all at once, but definitively, and then next time it will be harder) in the center of what still remains to artists: self-assured uncertainty. If memory serves me right, there have only been a few such exhibitions in which there wasn’t anyone for me to ask (Jan Merta in the Old Town hall in 1993 or Jiří Černický in 1995 in Galerie Pecka, the others will excuse me, I hope). Moreover, for now I can’t talk about a similar experience in the past five years. Maybe the reader would like to know where the will to make such a claim comes from: I don’t know myself, and I have no one to ask. The artist doesn’t know either, nor does she (why should it be otherwise) have anyone to turn to (by this she has most likely released me from a certain responsibility). But only this: Maybe it’s that here I feel as if we are personalities in a time of strengthening controls and uncontrollable self-control, how our obsessions (not those “dangerous” and “asocial” and “media friendly,” but quite simple obsessive images) become a part of the space of all who are together with us at this moment. Switching the program of a real landscape: joke, reflection of a reflex, critique, self-reflection? The trodden-on remains of a roll of toilet paper: document, return to what disappears every day, such an “aha” when we see the plenitude of a gap in life (more romance?), bitter humor. Wax stalactites, esthetic obsession. Everybody is making sexy art, but this is pure erotica. Candle with several wicks, unobtrusive finale. Golf green with balls, shelter, such a kebab (I quote the artist), vagina (I quote myself), children’s room before cleaning. Dusty road, matter-of-factness itself. Arranged coins, like when we were children… The important uncertain things.

01.02.2003

Empfohlene Artikel

|

|||||||||||||

Kommentar

Der Artikel ist bisher nicht kommentiert wordenNeuen Kommentar einfügen