| Zeitschrift Umělec 2004/3 >> Practice, Theory and Exposition of Zbyněk Baladrán | Übersicht aller Ausgaben | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Practice, Theory and Exposition of Zbyněk BaladránZeitschrift Umělec 2004/301.03.2004 David Kulhánek | profil | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

That which is really postmodern, open, plural and liberal is a reality of fictional dynamic structures, and that reality is constantly in flux. (Dušan Třeštík, Konec paradigmatu? In: Mysliti dějiny, Paseka, Praha 1999, p. 67)

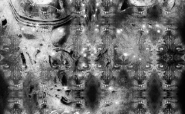

In art, as in society and the individual, one can find specific maps. Some lines present something, others are abstract. Some are with segments, others without... We think that the lines are constitutional parts of the things and events. Therefore everything has its geography, its cartography, its diagram. (Gilles Deleuze, An interview with thousand facets, in: Rokovania 1972 – 1990, Archa, Bratislava, 1998) Zbyněk Baladrán is a contextual artist. In his projects from the last two years he has formulated methods that can be applied to different segments of historical facts, events, theories and also purely personal situations. Projection (Projekce), which was first exhibited in 2003 and later in new variations such as Manifest 5, is an open project containing multiple layers. The starting point is a collection of films from personal archives. In the first stage, it included the extended family of Zbyněk Baladrán, who provided videos and 8mm films, and thus created a family archive of accidentally collected films. Other material was bought from individuals who reacted to his advertisement on the Internet. These movies (a half a ton of them) stored in the artist’s studio resemble archeological findings in their fragmentary structure. Their value as documentary is limited; they are well-known films from newsreels (an official Czechoslovak film periodical going on until 1989), trivial family videos or instructional films from the 1950s to the 1970s. Because of this limitation Baladrán works in this frame and presents the possible method of new reading of this material. The films were created in a certain time, and they are a record of historic circumstances and in general they represent the meaning currently attributed to film. Objective meanings and contents inserted into the “material,” exhausted over time. Their original purpose is blurred, they become less and less clear signs referring to the past (modernism) as historical phenomena that can be interpreted from a distance and updated in the conditions of today. The memory is still alive, in reach of present-day youngsters and to those who were present at events of the first half of the 20th century. Is it possible to objectify such experience? With a degree of difficulty, it is possible to reflect such a position, and the only way is probably the limitless method of Baladrán’s research. The gathered film material is a sum of information that can be sorted out, joined and interpreted thanks to inexhaustible possibilities of the edit. In Projection, Baladrán concentrated on the chronology—on the basis of a family archive, he charted post-war time in Czechoslovakia. On a solo exhibition Theory/practice/exposition (Teorie/praxe/expozice, The House of the Lords of Kunštát, Brno, april 2004), he experimented with a simultaneous projection of films with a similar theme (X-rays versus nuclear experiment). In one of the segments of Projection he interconnected (by simple edit) the fragments of two Czech films—one from the time of the Nazi occupation (Kristián), the other from the time right after the end of the war (Pérák a SS). For Czech people both films have the value of a myth (just like the art film). The films from the time of the occupation are more similar to the esprit of the time than with the context of war; on the contrary, Trnka’s postwar movie is a direct reaction to the end of the war in which the enemy was defeated. Both films represent a clear, readable but still difficult context. Through simple edits that set them into a new frame, a model pattern has been set for an anological method in working with other informations. While working with film fragments, Baladrán had another problem – our habit to read pictures as visual messages, even before we are able to think about them in a theoretical level (as of signs, functions, “material,” etc). The artist’s film collection transforms documents with a clear message into archeological fragments with an inventory number. Parts of the project are descriptions of the “method” (the way of material processing) and schemes (graphic marking of the coordinates of a given fragment, its time – in the frame of the whole of the film and the exact date of its origin). Recent history (effectively the story of modern day) works through our memory that remains in us, in things and stereotypes. We look at it from a distance, we can reconstruct it from fragments found in our immediate surrounding. An accidental configuration of the memory creates points in the map which represents cartography changed by the number of possible individual entries. Baladrán’s method seems like a bricolage as described by C. Lévi-Strauss. The product of research is not art work as an artifact (such as a new video or documentary), but an open structure, implying subsequent potential sources and contexts. Baladrán uses the accidental connection, records from the readings of theoretical texts and systemizes its application. In his new projects Zbyněk Baladrán doesn’t only work with the “Memory of film.” The subject of his research are urban folliage and airborne pollen (Neosamizdat NO.1, published by PAS in 2004) or a standardized mural ceramic lamp, which has been in production for decades and thus represents a persistent product of modernism (Bricked up entry /Zazděný vchod, 2004). Still open is the continuation of his research of discontinuity/continuity of the Czech art in the last decades, as we could see in the documentary vide, done in cooperation with Ján Mančuška and Zbyněk Baladrán (Vide, 2003). In the latest Baladrán videosketch (1,2,4,8,16, 2004) one can see an open sketchbook and a hand drawing a primitive geometric series—from each point two new points are produced. Thus a paradoxically chaotic structure arises, a kind of a cocoon of points and lines, that soon outgrows the well-arranged size of the area. An attempt to grasp at the whole, complex description of an abstract situation collapses. Objectivity, an exhausting genealogy of reality, is an illusion. In this skepticism arise Baladrán’s probes, ad hoc anamnesis, describing and making lists of things, facts, circumstances, momentary state of events...

01.03.2004

Empfohlene Artikel

|

|||||||||||||

Kommentar

Der Artikel ist bisher nicht kommentiert wordenNeuen Kommentar einfügen