| Umělec magazine 2006/3 >> ACAMONCHI | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

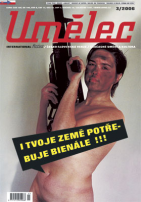

ACAMONCHIUmělec magazine 2006/301.03.2006 Marisol Rodríguez | street | en cs de |

|||||||||||||

|

To live in the media is to live in the ephemeral, if you are not in when they call, they just call someone else. If you call them, they never call back(1).

In 1994, Luis Donaldo Colosio was assassinated, shot in the head in the middle of a cheering crowd, after an enthusiastic speech for his presidential campaign in the northern city of Tijuana. All of a sudden, this city at the very edge of Latin America was once again in the eye of the hurricane. Tijuana is a paradigmatic city located on the Mexican-American border. It has become the perfect ground for the rising of a new scene(2) – musicians, artists and designers have imposed their aesthetics, their music and their way of mockingly perceiving, in the often corrupted, burocratic and frustrating Mexican reality, an alternative way of creating, and thus catching up with other artists and designers across the country. In Tijuana, instead of complaining about what is not, they make fun of life as it goes; they create valuable music, design and art to spread it around the world. A CAMONCHI, EXPERT IN STREET ARTS Gerardo Yépiz collects AVON bottles and openly loves cheap, “finding beauty in all that is common and popular” – so to speak (wouldn’t I be a good curator?). He was born in Ensenada in 1970 and has been living in San Diego since 1997. For the last ten years, Yépiz has been developing a project called ACAMONCHI. The artist mocks and yet uses the creation system in which he evolves: he doesn’t need useless scandal or any kind of slogan against it, his works speak for him. His constancy and tenacity are far more important than any replica. But then, how does a thirty-five year-old post-modern troublemaker, an academic designer – in a word a self taught artist- move around? Yépiz is a combination of workoholism, talent, technical specialization, and conceptual clarity. Most artists would die to have at least one of his skills; that is why it’s not surprising to see so many copies of his works. Mexico is an indebted country where law and order are uncertain. Nonetheless, we are the second largest world consumer of Coca-Cola, and the world’s second television watchers. We can walk around the city and bump into an indigenous person begging with a Burger King cup; our politicians spend fortunes on federal campaigns, and do you know what? We all know it and we don’t care. There isn’t any clear or concrete reactionary group working against all these things; the media is a sort of circus, an artifice showing the trickery in which we live. Design is the reiteration of the national stagnation of form, of thought and of creativity. In the middle, because and in spite of all this, ACAMONCHI starts in 1997 like a fanzine dedicated to the promotion of local artists and musicians. Soon enough, it becomes a whole and ambitious artistic project. At the beginning, ACAMONCHI is a recollection of cheesy icons, using idols and characters of the Mexican cliché, including Colosio, the murdered presidential candidate (who, six years after his death, had become a martyr, a brave and incorruptible man whose courage epitomized the national pride.) Everyone seemed to have forgotten his original image: a man who was to carry on the 70 year old hegemony of the PRI party, responsible for murder, fraud, massacres (1968), economic recession and much other spoliation). In a stencil, Colosio smiles and says “I’ll be back”. There are many other versions of it, including one with his face and the body of James Bond while the background is made of spilt blood; another one with Colosio wearing an astronaut helmet, he then becomes Astrolosio... What I mean isn’t that ACAMONCHI is critical towards the government, nor that it’s any kind of social or political activism; what I want to state is that ACAMONCHI is more like a teenager’s reaction to what happens in Mexico or in the USA – it is what we all have said about our government in certain moments, -dirty bastards! – or the attitude we had towards our parents when we were teenagers – when we were unbearable, cruel, mocking and cynical. There is no lineal thought in its work, so there is no direct message – almost all the frames and almost all the stencils look like a series of dispersed ideas (that together, usually, make sense). We can always try to understand, but it all remains a personal interpretation of what could be (or not) a simple joke for us, for anybody, even beyond ACAMONCHI. In the absence of centralized and hierarchical control, localized interventions in the structures of cultural reproduction and social production become not only entertainable but sometimes even entertaining(3). He calls it Absurdist Propaganda. The apparently senseless intervention in a public space dominated by political propaganda: if the candidates can promise any kind of stuff, and rely on people’s naivety, ignorance or absolute stupidity, why wouldn’t ACAMONCHI do the same? There is a moment when anaesthesia, the blasé attitude (Georg Simmel) makes us deny and ignore all that is bad and uncomfortable around us: we lock ourselves in a closed sphere after being over stimulated, after having all our senses alerted to situations as common as going home from school in a city like Mexico City. We create our own anaesthesia; this will allow us to go through all sorts of experiences, without the torment of really perceiving what makes us feel uneasy. But what happens when there is something shocking in our “merry”-go-round, something unusual in our aesthetical panorama, something that will make us react, in spite of our old domesticated brain... then we notice something we had seen many times, but never really looked at. ACAMONCHI stands for that confusion, that bombing (we never wanted it, but maybe we deserve it) from which we are captives everyday. It uses our own apathy while adopting the street (a formerly disdained milieu) as a canvas and, moreover, as an endless source of ideas, drawings, vernacular typographies, kitsch illustrations, cheesy messages and bizarre representations. One of the main influences of ACAMONCHI is punk music. “I never developed any musical skills. For me, punk was the exchange of fanzines, tapes, to paint our t-shirts, jackets and skateboards. My favourite punk groups are Crass, Subhumans, Discharge, Rudimentary Peni, GBH, Butthole Surfers, Dead Kennedys, Political Asylum, Blut & Eisen, Neurotic Arseholes, Terveet Kadet, Conflict, Flux of Pink Indians, Drunk Injuns, Minor Threat, Final Conflict and a lot more”. Yépiz defined himself as a self-taught man, with the right of unconformity, but he also thought about being congruous and, moreover, decided to be pro-active and work for change, instead of complaining and hiding in empty and obsolete apathy. ACAMONCHI is, and has always been, autonomous: Gerardo Yépiz has never had any kind of grant; he has never had a sponsor or patron, wealthy parents or the sufficient income to afford university. In spite of this, he never complains. He is proud of this independence. To take photos, editing, printing positives, to burn screens, print posters, t-shirts, stamps, to put up those posters, to sell those t-shirts, to spread those stickers around the world is part of Gerardo’s work – he has no time for posing like all those artists we have all – unfortunately – known. Whether it is in a poster, a painting or a t-shirt design, we find constant features in his works, like graffiti or Pop Art influences; the graphics and techniques will usually include aerosol and serigraphy; the stencils (that can be small like a common sheet of paper, or reach 3 meters in height) represent popular icons from Mexican music, politics and media. The palette is rather strange; Yépiz usually buys his materials at painting sales, among the “rejected colors”: that is why we can find awful and yet seemingly new kinds of green along with other colors creating analogies, or, as often, monochromes. The textures are a fundamental part of his work; it’s very common to see compositions that follow golden reticles, in long-limbed shapes – second-hand wooden pieces- sometimes saturated with textures and full of unrecognizable figures. This is one of the main strategies of ACAMONCHI: saturation and intentional ambiguity. He forces the spectator to pay attention, to put themself in context, and to react the way he wants to what the artist proposes. It isn’t very hard to understand, we don’t need complex theories or to pretend we’re scientists discovering the black thread. That is what makes his work so refreshing, it doesn’t pretend to be what it is not: ACAMONCHI shapes what is happening, what we didn’t want to see, but that actually looks great with a few hints of orange; it states that there are no terrible things that we couldn’t change. ACAMONCHI reminds us that there are insignificant and despised things that belong to our daily world as well, and instead of replacing it with a Japanese designer toy, we could rescue those things, even if we consider them garbage. His work says that maybe Mexico isn’t what the media wants us to believe, that it isn’t that bad, and that there is a funny side of living in constant infatuation, and to play with it, to laugh about our subnormal politicians and the bureaucracy, about artists, curators and critics that try to make poetry out of every piece of incongruence that is presented to them. (1) Mark C. Taylor, Esa Saarinen, Imagologies, Media Philosophy, 1996. (2) NORTEC, a movement created by bands of electronic music, using samples of “Banda Sinaloense” among others; drums, percussion and trumpets used in traditional Mexican music. It has become a real movement, including designers, artists and architects –cf. Tijuana Sessions. (3) Mark C. Taylor, Esa Saarinen, op. cit.

01.03.2006

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment