| Umělec magazine 2009/1 >> At arm’s length | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

At arm’s lengthUmělec magazine 2009/101.01.2009 Milena Dimitrova | review | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

Contemporary art that engages with Eastern Europe tends to be viewed from a purely Western perspective. Bulgarian artist Kamen Stoyanov, an artist as an observer, makes no attempt to evade this question. Vienna’s MUMOK in Vienna played host last year to the exhibition “at arms length” by Stoyanov, in connection with the awards ceremony of the Viennafair. This exhibit took as its theme the relations between the post-socialist East and Western Europe regarding cultural translations, questions of identity and cultural phenomena.

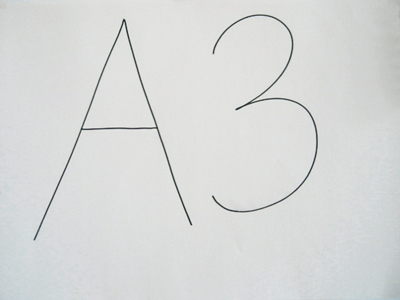

The phenomena associated with post-socialism, the art market, the all-encompassing economization of so many areas of life, cultural identity, and the position of the artist—all of these themes are expressed through a variety of media. This tendency could be seen in At Arms’ Length, the series of drawings Brakeshoes, the video Move Your Hands, the installation Tigersteps and the video-work Persona. Persona was the most important work in this exhibition, serving as a thematic summary of all of the works presented under the banner of cultural translation. In this case, gaps and breaks in cultural and artistic identities are of particular interest. There are moments in which these identity clashes occur, as, for instance, in the Brakeshoes cycle, which treats the possible intercombinations of the A3 paper format and the Bulgarian first-person pronoun, rendered in Cyrillic lettering as A3. One particularly thorny thematic question of these sketches is posed by the Cyrillic alphabet, itself regarded as a barrier (“Hemmschuh”) from intercultural communication in the widely popular 1944 work on world languages by the Swiss philologist Frederick Bodmer.* Of particular note is one passage from the book on the inability of Russia to reach out to the much-desired cultural treasures from abroad: “(...) The Serbs and Bulgarians also drag this cultural burden along with themselves, but not the Poles and Czechoslovaks. When their forefathers were adopted by the Roman Catholic faith, the Latin alphabet came as a gift from Rome.” This quotation serves as the point of departure for these sketches, introducing a thematic framework for the conflicts of culture and identity in modernity within their differing contexts and external forms, and allowing them to be represented visually. Hence, this work takes up more broadly the customary idea of the artist as a skilled draughtsman, as well as the preference among gallery owners for the medium of drawing, one that can be sold more easily than other, less traditional media. The charm of these drawings lies in their logic of similarities and transformations, in which thematic or formal qualities are transferred from picture to picture. For instance, a “perfect circle” drawn by one artist appears on one sheet, while on the next, a bite has been taken out of it. Even the way in which the drawings are stacked, in a careless heap, could be seen as simulating a pile of money. Along with the theme of identity, this formal principle is carried further in the video installation Persona. This work displays a woman performing a simultaneous interpretation of Ingmar Bergman’s film of the same name during a screening at the Odeon cinema in Sofia. It is hardly an accident that Bergman’s “Persona” is the film selected: a work in which the central theme is that of identity and the problems that grow out of it between two women. In the film, one of the women is speaking in the name of the other, and the interpreter in Stoyanov’s video assumes a similar role, even through her own external similarity to the actress re-inscribing the process. Much as in the drawings, what transpires in the video is a highly ambiguous, multi-layered process of identity-shifting. In Persona, Kamen Stoyanov took inspiration directly from Walter Benjamin’s text “The Task of the Translator,” in which the central idea, put simply, is that translation is always an extension and transformation of the original, making the original more comprehensible, and that breaks, imprecisions and fissures in the process of translation, which paradoxically arise through literal faithfulness to the original, lead straight to the actual, hidden meaning of the text itself. A literal translation proves to be an error on the part of the translator, and a quality that unexpectedly lends transparency to the original—an idea that applies not merely to linguistic translation, but even to that of cultural, economic and social phenomena. One example of the idea of an all-too-literal translation appears in another of Stoyanov’s works, the Tigersteps installation. A stuffed tiger, almost life-size, relates the life-story of the Siberian tiger Shakti, who spent four months as an attraction in the hip (yet short-lived) Tiger Steps cafe in the Sofia’s massive Tzum shopping center, surrounded with all possible comforts from flat-screen TV to air-conditioning. Photographs and tiger-shaped accessories from the place where it all transpired serve as evidence of the verity of this story. Following the stated logic of translation, the expression and appearances of capitalist economics reveal themselves in essence once translated into the formerly socialist East. Their implantation, often absolutely literal and presented in pure form, allows this economic system to emerge in its most radical, most pure manifestation. This work does not criticize a deliberately imprecise translation or incorrect interpretation of the market economy, but instead finds concealed in its “mutation” and “misunderstanding” the potential for enlightenment as well as disturbance. With a stuffed animal that repeats (through a cassette tape, in overly affirmative tones) the views of its owner and advertising slogans for the cafe, Tigersteps is, though, simultaneously the most “talkative” work in the exhibition. With notable ambiguity, the installation is located between the floors, in the museum’s transition space, in “transit” to that point where the East is to be localized. A place that creates the necessarily troubling ground for any “self-colonization.” If the exhibition makes a statement that should be interpreted, it is only to create from the critical potential of translation.. *The Loom of Language, Frederik Bodmer, London, 1944. A guide to foreign languages for the home student.

01.01.2009

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment