| Umělec magazine 2005/3 >> JERZY KOSAŁKA - Swallowed by a Small Dog | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

JERZY KOSAŁKA - Swallowed by a Small DogUmělec magazine 2005/301.03.2005 William Hollister | poland | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

After the gradual decay of Soviet rule in Poland in the 1990s, a loosely organized group of artists, gathered under the name Legendary Luxus, pressed forward with artistic perspectives that radically diverged from what had been presented to the regional public by cultural connoisseurs as an “avant guard” trend of Polish Conceptual Art. Replacing those movements’ pale Abstract Expressionist gestures—smudged by formalist black and white reference points aimed at the intellect—Luxus, in several exhibitions from 1991-1997, splashed Polish galleries with a bright plastic pastiche of ideas begging to burst forth in the last decade of the 20th century. Included among the then Luxus artists was Jerzy Kosałka. Born in 1951, Kosalłka continues to produce the ironic commercial banners of before, but his solo projects are increasingly refined. On the surface, he reflects the Polish embrace of commercial culture in the 90s; yet, his critique of the place where he lives has taken him further.

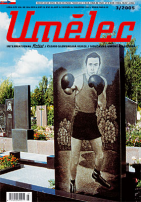

For a recent exhibition opening Jerzy Kosalka publicly promised a disappearing act. At the opening of his December 2004 exhibition at Wroclaw’s BWA gallery, with media panache he had hinted then at something grand: a magical performance on par with American pop-magician David Copperfield. An expectant vernissage crowd was further led on by the jazz music from three stand-up double-basses. Paparazzi stood by at the gallery’s neo-classical atrium in eager anticipation. But after all the media magic, Kosałka simply slipped behind a velvet curtain. It wasn’t even that: the curtain was a mere scrap of green drapery suspended by the gallery’s curators in front of a staircase leading to back offices. Confronting his own self-generated media pretence of grandeur, he made no attempt at any promised prestidigitation. This small performance encapsulated the humor of this artist—the flavor-of-the-month and the heartbeat of contemporary art in Wroclaw, a city itself reaching for grandeur, but caught in the clutches of grandiose Eurozone development projects. Kosałka’s artwork has for two decades followed a similar model. Large ideas—of subjects dear to Polish cultural history—are rendered very small, often to comic effect. Wrocław’s BWA Awangardia curator Paweł Jarodzki justified such gestures in the artist’s 2004 catalog: “The uniqueness of Kosałka lies in the fact that the key to his creativity has been swallowed by a small dog. The dog escaped and now we all look for him.” In recent exhibitions, telescopes are strategically set aimed at small points on gallery floors. Gazing through the lens, one focuses on small railroad-scale models, some of which are of the artist himself. Perhaps the uniqueness of Kosałka is the way his evolving engagement with his native Poland is consistently rendered toy-like to bring out unanticipated ironies, challenging established cultural idioms with insidious wit. In this way the Polish trauma of their defeat to the Germans in the Second World War is represented by the communist era two-tone packing paper of a sort that had been mass produced and popular in the Communist era in Kłobuck Battle Plan (1986). For simplicity, captions clarify a battle immortalized for schoolchildren in the poetry of Władysław Broniewski. A statement clarifies that the red signifies “us” and the green “them.” In variations, the colors are reversed. The later sculptural work, Germans Have Already Come (2003), is as a clever critique of the Poles’ persistent fear of Germans. Wrocław, a town declared a “Festung” by Adolf Hitler at the end of the Second World War was significantly damaged by Soviet troops. The surviving population of the city, formerly known as Breslau, was forced to resettle elsewhere in Germany; the Wehrmacht soldiers who had surrendered were deported to Gulags in the East. The city’s present, Polish inhabitants, represent a healthy young population of individuals whose families were displaced from the present Ukraine and elsewhere, from what was once Eastern Poland. To commemorate that mass relocation, and resettlement in former German territory, a tall pinnacle was built adjacent to the former “Jahrhundrets Hall” a lugubrious concrete domed stadium that formerly featured Nuremburg-like Nazi rallies. Kosałka’s version is very small, with tiny toy German soldiers crawling about the Polish pinacle’s base. Imagery of a well known American soft-drink company is ubiquitous in Kosałka’s work. Giant banners like totalitarian flags bear a logo that at first glance appears to say “Coca Cola.” At closer look, the artist’s own name is clear. Corresponding bottles are adorned on plinths in red—and blue, for a menthol-flavored variety. In addition, the artist, having crafted his identity in a cola commercial way, elsewhere presents himself at a black marble-veneer plinth, with his name in gold juxtaposed with the word, Nation (Tribute to Kosałka-1993). Although complete with flowers placed before it, as if to war-dead, the monument itself supports nothing. The medium is the message, and the content is emptiness; the altar is of the individual, but it is inhabited by empty space. Kogeneracia co., a heating plant that sponsors some of the artist’s exhibitions, despite being coopted the artist’s pop wonderland, plays a significant role in the artist’s imagery. Accompanying a perfect model of the catalog sponsor’s industrial buildings Zespol Elektrocieplowni Wroclawskich-KOGENERACJA S. A. (2002), Kosałka installed a work mimetic of that company’s Neptunian processes—a small white enamel bowl with a shallow puddle of water, under a low, suspended electric lamp entitled Instalacia Wodno-elektaryczna (1993) forms a discrete centerpiece to his recent expositions. A model of the hydro-electric company was set appropriately by the bowl rendering literal what the Duchamp-like ready-made alluded to. Elsewhere, the content isn’t so empty, but Polish national culture is caught off guard. Enshrined in Krakow is Leonardo Da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine. Poland is often described as a country whose culture is split between Krakow, the ancient Polish capital, and Warsaw, rebuilt and modern. By contrast, Kosałka’s Wroclaw is neither. It’s just there, and as such, strange things can transpire in a city whose present Polish appearance is an awkward palimpsest upon a previous Prussian-Silesian patrimony. Here, Kosałka’s version becomes Lady without an Ermine (2004). The picture, in the spirit of Marcel Duchamp’s Mona Lisa, features the famous Krakow image, but the furry animal has been sliced out, leaving a torn-open space revealing exposed wall in the back. The animal is not gone, however: a stuffed ermine is perched on the left-hand corner of the damaged painting’s frame, returning the viewers gaze with the cold authority of the creature in the original painting. This 21st century admirer of that proto-Dadaist, also reproduced Duchamp’s bearded Gioconde, placing a print of it above a floral towel and rack accompanied by shaving materials. For the same series, Pardon Marcel (1995), he presents a modified ready-made urinal—one incorporating a fountain bubbling menthol-green water. Finis Silesiae Because Kosałka’s exhibitions interlace such older Luxus work with the newer there is a subtle evolution. In retrospect the Luxus group in its brief existence comes across as an invention of US foreign policy. They were “In your face, pop and shocking“ as Jolanta Ciesielska described them for a 1997 catalog, with no apparent sense of irony. Instead of engaging in politics and meditating on the trauma of 40 years of Soviet occupation, Ciesielska says the artists took on the inadequacies of the local reality and “transformed them into an ironic Polish version of the American Dream...a world dominated by consumerism, entertainment, prosperity and democracy.” When Kosałka, the “tireless builder of facetious constructions,” broke away from that seminal collective with his first solo effort with the 1995 exhibition entitled Modestly, No Luxus, it at first appeared that he would continute with the core commercial tradition of that western - supported collective. However, there are aspects of Kosałka’s background that have brought the artist, a commercial prop builder for supermarkets, to craft an increasingly subtler critique of his environment than the barbie-doll empire of his hedonistic cohorts (and their international sponsors would allow). In the artist’s background are two key figures: Andrzej Urbanowicz and Henryk Waniek. Urbanowicz, in contrast to the artist here discussed, paints in a spiritistic, illuminist idiom. Waniek, likewise an artist working far from commercial hype, is a author and artist whose awareness of the Silesian landscape discusses past and present residents of the Silesian region with a startling literary sensitivity. One can only wonder how Koszalka began his artistic career associated with this background, only to later embrace pop icons so dramatically. If, by contrast, Kosałka’s maniac marketing formula seems at first somehow hackneyed, it must be respected that in the local context—Wroclaw and Central Europe—it speaks to the people in the town, and a younger generation is drawing inspiration from it. Such art is pushing the boundaries of visual culture in cosmopolitan ways, but ways that can only come from a city such as Wroclaw. These are not Duchamp’s ready-mades, they are the language of the present generation of artists and the next generation is listening.

01.03.2005

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment