| Umělec magazine 2000/6 >> Joker on the Loose (Iepe Rubingh) | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Joker on the Loose (Iepe Rubingh)Umělec magazine 2000/601.06.2000 Vladan Šír | artist | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

They took him to the police station for interrogation. But he’d counted on this and had consulted his lawyer beforehand who explained to him all the possible penalties, which ranged from a pardon to fines and imprisonment. He was anxious to find out what scenario the uniformed peacekeepers would pursue. Still, he and his lawyer would plead for the mildest possible punishment. After all, he thought, I haven’t really done anything that bad.

Twice, in two countries on two continents, the Dutch artist Iepe B. T. Rubingh has transgressed law and order by causing total traffic breakdown and chaos in the open thriving jungle space of a large city. For a bare few minutes, he succeeded in rupturing city life’s steady pulse when he and his assistants cast a singular net through the streets, cutting off traffic and snagging unwary pedestrians in their tracks. Berlin, on the evening of 1 October 1999 Slow moving taxis, trams and pedestrians all zigzag their way through the intersection, Hackesche Markt, in the neighborhood of Mitte. People lounge in bars and restaurants, talking and drinking while keeping half an eye on the street. This day was no different. Nobody suspected anything. A small group of people, led by Rubingh, inconspicuously slipped among the ambling pedestrians and assumed strategic positions. Without warning they suddenly streamed across the intersection trailing long plastic strips of red-and-white barrier tape, which were fastened to poles on the sidewalks. They crisscrossed randomly through the intersection while shedding hundreds of meters of the bright tape. Within seconds, they had transformed the space into a spider’s web, the trajectories of cars, trams and pedestrians frozen in the moment. Surprised drivers poked their heads out of car windows. Pedestrians tried to wind their way through the tightly bound tape. Trams disgorged their passengers directly into the snarled nest. Nobody understood what was happening. The clapping and laughter of the colluding transgressors sliced through the chaos. Soon the people trapped in their cars started laughing too. Those passers-by lucky enough not to get entangled in the net quietly observed the confusion. Nervous taxi drivers tried edging forward in an attempt to break the confounded tape and escape the trap. The next few minutes were filled with waiting, for the police to arrive, for the detainment of whoever had disrupted the day, for the unraveling of the barriers from the street. Tokyo, on the evening of 11 March 2000 The Shibuya intersection is located at the edge of a popular neighborhood of the same name. It is much bigger and busier than the intersection in Berlin. Taxis shunt through in several lanes and hundreds of people shoulder their way out of the underground every minute. When the light blinks green, cars hurl in several directions while pedestrians patiently bide. The entire space is illuminated by blinking light advertisements and large projection screens. Suddenly, this evening, a figure in a black-and-yellow striped suit wearing a joker’s hat pops up out of the crowd. At that moment, the colluders move from their corners. The red-and-white barrier tape unfurls through the intersection. When the constructed chaos is at its peak, the joker mounts a plinth in the middle of the crossroads and begins to orchestrate the event with the flags in his hands. The traffic smacks to a halt and Rubingh is engulfed by a crowd of clapping and cheering people. Soon the police turn up at the site and take the performer to a nearby station for interrogation. The Joker This chaotic performance, featuring an intersection, a means of transportation, the public, 5,000 meters of barrier tape and the police, does not change in essence. Rubingh however counts on the event to take on different significance in different locations. “Although the form remains the same, the direct meaning will differ according to the environment it is set in,” he writes in his concept for the performance. “[The form] will work with the tensions and problems specific to the location and culture. It will work with the energy and frustrations of the people who are daily faced with these negative sides of their surroundings.” When a casual pedestrian or driver is caught in a situation created by Rubingh, the person may question something that would have been there anyway, even if this were not a performance: Who’s this madman stopping the traffic in the middle of the city? What does he want to achieve with this? Is he some kind of a political activist or terrorist that he dare disrupt public order? Is this yet another demonstration? Or is he just some kind of a jerk who’s lost his marbles? Because Rubingh dons the garb and role of a joker in his performances, the last of the questions is not far from the truth. The joker represented an autonomous institution under absolutist regimes. The ruler allowed him to joke at his expense, to flout the social order defined my him, to tell the cruel truth without fear of punishment. But you won’t find an absolute ruler in today’s representative democracy, and it seems the institution of the joker has no place in it either. On the contrary, autonomous institutions that are not directly subordinate to the creation, execution, and maintenance of power under democracy challenge its position, reflect it, and are therefore often considered suspect. Hence Rubingh asks, “What is a kingdom-society without a joker?” He is interested in the response to his joker antics from both the public (the originator of power) and the police (the protector of power). “It will be interesting to see whether or not this position can be maintained in different cultures. Will different societies allow themselves a joker? Will they accept the work as a piece of art that contains social criticism, or will it simply be seen as a criminal act?” The public in Tokyo was divided in its opinion of the performance. While young people appreciated it for making fun of the police, the elders rejected it because they considered it an anti-societal activity that deserved to be punished. As a perfect autonomous institution functioning in a representative democracy, Rubingh’s performance featured, as he later assessed, “elements of surprise, improvisation, individuality, and confrontation.” These, he said, were “the elements the young Japan understands and the old Japan has never heard of.” Consequences In Berlin, Rubingh tried to present his performance to the law as a spontaneous demonstration, which is legal in Germany and does not have to be reported in advance as long as its preparation takes no longer than half a day. He even made a flyer with intentionally ultra-leftwing text. It was intended for the police and was not the point of the performance. After he was detained, the police listened to the rehearsed story, and they were forced to let him go. A month later, however, he received a summons and the investigation continued because it turned out that the law states that the time for preparing a spontaneous demonstration is only four hours. With the help of his lawyer he got out of it by paying a donation, and not a fine, of 500 DM. The police in Tokyo were not so sympathetic to his story because they suspected Rubingh of being a terrorist. First they detained him for a day to conduct an interrogation and then they set him free. A few days later, a dozen police officers piled out of a van and arrested him again. This time he spent ten days in prison during which the investigators gave him the knuckles and bright lights while searching for the people who had assisted him in the performance. In the end the judge believed his story and let him go after he paid 50,000 yen. Like a joker to a king, Iepe Rubingh asks, “I’m sorry, but it’s funny, isn’t it?”

01.06.2000

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

|

04.02.2020 10:17

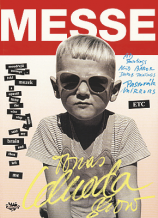

Letošní 50. ročník Art Basel přilákal celkem 93 000 návštěvníků a sběratelů z 80 zemí světa. 290 prémiových galerií představilo umělecká díla od počátku 20. století až po současnost. Hlavní sektor přehlídky, tradičně v prvním patře výstavního prostoru, představil 232 předních galerií z celého světa nabízející umění nejvyšší kvality. Veletrh ukázal vzestupný trend prodeje prostřednictvím galerií jak soukromým sbírkám, tak i institucím. Kromě hlavního veletrhu stály za návštěvu i ty přidružené: Volta, Liste a Photo Basel, k tomu doprovodné programy a výstavy v místních institucích, které kvalitou daleko přesahují hranice města tj. Kunsthalle Basel, Kunstmuseum, Tinguely muzeum nebo Fondation Beyeler.

|

New book by I.M.Jirous in English at our online bookshop.

New book by I.M.Jirous in English at our online bookshop.

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment