| Umělec magazine 2011/1 >> Lobotomies at every turn | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Lobotomies at every turnUmělec magazine 2011/101.01.2011 Alena Boika | essay | en cs de |

|||||||||||||

|

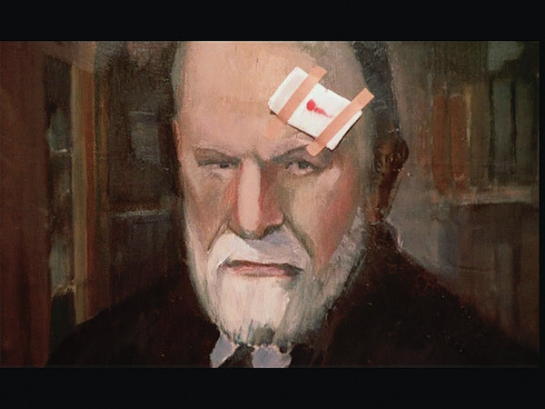

Winter is over; summer’s begun –

Thanks, dear Communist Party, for the seasons again. This is a once-popular couplet that any citizen of the former USSR with at least some sense of humor had no trouble understanding. Despite its sad irony, this laconic rhyme could bring a smile to their faces. Summer was over, autumn had begun – and there I was again, face to face with these strange creatures that could hardly be an invention of a certain political party, considering the current multiparty system and the “predominance of democracy” – as global and comprehensive as this sophisticated approach seemed to be. I had first encountered them in spring. Passing by the famous landmark building on Prague’s Národní třída (“National Avenue,” the name of a street and a metro station) – where the communist-era Maj department store (“May,” in reference to May Day) has been replaced by My (Czech for “us”, i.e., a store that wants to be closer to the people) – I suddenly stopped, struck by the unusual nature of what I was seeing. A window display was filled with clothes mannequins looking as if they had just been given a lobotomy. At first, I thought that maybe they were being repaired or that the artist who had created them had had a springtime fit of schizophrenia… But then I saw them again, this time in the fall – more mannequins subjected to the same surgery. Okay, someone might argue that, technically, it wasn’t lobotomy but just some kind of artistic craniotomy, but I would disagree. Some quick background information Lobotomy is the surgical removal of the frontal lobes of the brain responsible for self-awareness and decision-making. Lobotomy was developed in 1935 by Egas Moniz, a Portuguese neurosurgeon. The procedure caused irreversible damage to the human brain and thus was advertised as a means of salvation for hopeless situations. After a lobotomy, the patients would be diagnosed as having “frontal lobe syndrome (code F07 in ICD-10)” for the rest of their lives. After Moniz received the Nobel Prize in medicine, lobotomy found more widespread application. The American psychiatrist Walter J. Freeman led advocacy in support of this surgical procedure. According to Freeman, the procedure’s objective was to remove the emotional component of the patient’s “mental disease.” The first operations were performed using an icepick. In the United States in the early 1950s, about 5,000 lobotomies were performed each year. In the meantime, the operation began to be strongly criticized on ethical grounds. It was viewed as maiming the patients and damaging their brains. As a result, by the mid-1950s the average number of lobotomies per year declined sharply. In the Soviet Union, lobotomy was officially banned in 1950. There are no clinical data available as to the massive use of this procedure in other countries. According to psychiatrist Michal Wimmer, the number of lobotomies performed in the Czech Republic is considered classified. Just like in the movie In Jos Stelling’s The Illusionist (De Illusionist, 1983, 90 min.), a dramatic family saga unfolds in front of us: two romantic young men, neither of whom has ever lifted a hammer or a plough in their life – “the pillars of civilization” as someone erroneously suggests (well, perhaps, but certainly never its “engines”) – try to change the world by merely living in it in a way they like and find interesting… even if collecting flies, for instance, strikes some as strange… even if cynics sneer at the sight of their great invention, A Very Orange Plane – made from a bicycle in a fit of ecstasy. They love bright colors, magic tricks, white mice, and simple wonders that they arrange themselves. They are not afraid of exposing themselves to ridicule and care nothing about having a “bird in the hand,” preferring to pursue their free, boundless and enthusiastic dreams. The older brother, however, has fits of love-hate, and the community decides that he is dangerous. They might even be right: It really is better to avoid love, for it can stir up all sorts of ideas and cause all sorts of disasters. The people quickly place him in a clinic where patients with identical scars on their foreheads all obediently watch performances and eat carrots. After his next fit, the elder brother undergoes a lobotomy and is turned into a meek creature, devoid of aggression. But only until “the fight over the eye-glasses” and “the vision.” We should mention here that both brothers wear glasses with thick lenses, which they sometimes lose, break or try to take from each other. The glasses form one more layer of this multi-layered film. The brothers (who can see what is “different”) have been given the privilege of seeing the world through this (alleged) optical device. The same defect causes them to look closer at details that are invisible to others. Fascinated, they observe insects and people, and don’t see much of a difference between the two. Except for their father, who also wears glasses, the other characters do not have the same privilege. The constant leitmotif of the loss of or damage to the glasses represents the danger that the brothers might be forcedly displaced into the world of “normal people,” and thus deprived of their wonderful ability to see the “different.” Their own reaction to such a possibility is unpredictable, sometimes approaching violence on the verge of murder, which eventually happens. However, the movie does not depict this death as tragic, rather showing it ironically. What is really frightening is the loss of identity, of one’s “emotional component,” and the transition to the world of “normal people” – a transition that is akin to spiritual death. Trying to sort all this out, the younger brother first notices a strange scar on the forehead of one of the men carrying the coffin containing the body of his cheerful father, who has committed suicide. This makes him remember the insipid grin on the face of a responseless idiot he had encountered in the psychiatric clinic while visiting his brother. That particular person’s head was wrapped in a bandage with a bloodstain on it – exactly at the place where the man carrying the coffin had the scar. From this point, the story speeds forwards and spirals towards its conclusion – the elder brother’s lobotomy. Attention: the question arises as to why a few frames show the scar on the right side of the forehead, while the rest of the patients have it on the left. Why does he still show interest in his younger brother’s pair of glasses and tries to take them from him? He was supposed to have become a “normal” person, a meek patient who does not need to see. The younger brother falls down and hurts his forehead, and we see blood on it – right at the place where lobotomies are performed. The answer suggests itself: the elder brother is just a mirror reflection of the younger brother; it is up to the viewer to decide whether he has already been subjected to a lobotomy, or whether he is still trying to resist it. DIY lobotomy If we consider all of the effective methods of brainwashing used on their citizens by governments around the world (including such massive and effective tools as television and other mass media), lobotomy strikes us as an extremely unwieldy mechanical solution. It is, however, a surprisingly simple method, and the procedure does not require any special medical knowledge. In fact, one great advantage is that the patient can carry it out himself, if necessary. The operation involves three simple steps. 1. External anesthetic is applied to the skin over the eyes and a horizontal incision is made. A patient engaged in autolobotomy should apply minimal anesthesia or he will not be able to sufficiently focus his eyes. Experts recommend performing autolobotomy without anesthesia. 2. A narrow metal blade is introduced in the incision at an angle of 15-20 degrees to the vertical. The blade must be entered upwards until it touches the dura mater of the brain. A cone of brain tissue is then cut out with the blade, with the tip of the cone at the bridge of the nose and its base measuring about 3-4 cm across. Since brain tissue is insensitive, the patient does not experience any discomfort except for the usual inconveniences associated with such an operation. 3. A flexible tube should be introduced in the incision for the removal of excess blood and cell mass. The incision is then sutured, and if the surgery is a success the patient returns to work a week after the operation. So, if you wish to support the government of your country in its efforts at creating a normalized society – i.e., a society in which self-consciousness and excessive “emotional components” have been totally eliminated – do not hesitate. Act right now! After all, if a shop window on large city street can display male, female and even infant mannequins bearing the telltale marks of lobotomy, this is clearly an indication of what trends await us in the coming season. It is in vogue “to remove the frontal lobes of the brain responsible for self-awareness and decision-making.” Even if the scars aren’t exactly in the same place as they are in the movie – well, that’s fashion. Generally speaking, the larger and deeper a government’s interventions, the more they prove the sincerity of its intent. ... At the seventh conference of the Neurosurgical Board of the Soviet Union (1946), the famous Soviet neurosurgeon N.N. Burdenko, speaking of the importance of surgical intervention in the human brain, refuted the view that psychosurgery is “the music of the distant future.” He would surely be happy to know that it is, in fact, “the music of the coming season,” growing louder and louder all around us. *Sources: Wikipedia and www.pseudology.org Translated from Russian by Elena Dyuldina.

01.01.2011

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

Add new comment