| Umělec magazine 2005/3 >> NOT THAT PAINTING, THE OTHER ONE | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

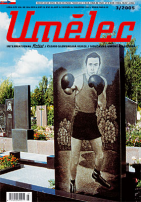

NOT THAT PAINTING, THE OTHER ONEUmělec magazine 2005/301.03.2005 Mihnea Mircan | study | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

The exhibition at Bucharest’s new Museum of Contemporary Art, The Painting Museum, is a study of the portraits and styles of portraiture associated with Romania’s Communist dictator Nicolae Ceauşescu, and depictions of socialist progress. Never seen juxtaposed outside their original context, these paintings—presented in a panoply of styles inside an edifice that formerly served as Ceauşescu’s home and seat of power—illustrate how the grand narrative of ideology, party and political brutality becomes intertwined with an infinite number of biographies, destinies consumed in the absence of any sort of collective meaning.

Sabin Brăaşa’s Moment of Fame There certainly is no other way that the Romanian painter Sabin Brlaşa would make it to the pages of Umelěc magazine. BrlaLa speaks like Michael Heizer on acid about the figurative holes he has drilled into the collective psyche of the Romanian nation; the blue of his backgrounds is supposed to imply some mystical depth for either trite allegories or for spiritualized portraits (those of Nicolae and Elena CeauLescu before 1989 and those of the present-day nouveaux riches). Sabin BrlaLa is suing the French newspaper Le Monde for mis-attributing a painting to him, demanding one million euros as moral compensation. Le Monde featured an extensive article on Romania’s new Museum of Contemporary Art (MNAC) in Bucharest, its politically charged location and a show that was on at the time: The Painting Museum, that explored the largely uncharted territory of official art in communist Romania, looking at politically submissive art in the very location it was supposed to adorn and glorify. Among other illustrations, there was an image of the presidential couple – the object of unrestrained artistic adulation – holding up a rather nondescript, statistical child to an invisible yet presumably inflamed audience. The scene bespeaks victory, yet it’s not at all clear whether what was on display was an offspring or the product of social engineering – the new man – and if the gesture was directed towards an optimistic future or to humiliated history. The journalists looked inattentively to the museum’s website and printed the wrong the caption for the painting: Sabin Bălaşa’s was the next one, and we are left wondering whether there was truly a substantial difference between the two and, if so, what that substance was. The lawsuit was motivated by the fact that the misattribution was a “denigration of the country on the eve of its admission into the European Union,” and one can already sense the mesh of conflicting criteria that is contemporary Romania. With Le Monde and other reports, the international media coverage of the show was generally confined to noting the exoticism of works and situation, while local journalists jubilated over the more grotesque images (as if some other, distant nation had produced them) and a sense of reprisal prevailed over analysis. An important set of reactions came from Bălaşa’s peers, the “masters” of Romanian painting, featured extensively in the show, who either disputed the necessity of the project or defended their position stating that they had no alternative but to paint the leader and that, after all, good painting is not a matter of subject. Superimposed, as was often the case, these two arguments amount to a perfect contradiction, whereby alleged coercion encounters an equally dubious apolitical triumph of the aesthetic. (In passing, it should be noted that the odd title of the show engaged the tacit or vocal aspiration of this generation of artists that MNAC would become a ”museum of paintings,” fully acknowledging their contribution to the advancement of fine arts in Romania.) Portraying the Dictator, Again and Again Curated by Florin Tudor, The Painting Museum exhibition at MNAC had been intended as a first step in a systematic study of the works—portraits of Romania’s communist president, Nicolae CeauLescu, or depictions of socialist progress—aiming to articulate an iconography of communist power, with a study in aesthetic deviance and social pathology as inevitable by-products. These works had never been seen side-by-side, outside their original context of the annual ”homage” to communist leadership, and this phase of ‘visualization’ will grow into a long-term, cross-disciplinary project, bringing together more case studies of former communist countries. Although the border keeps shifting, curatorial gestures in general could be roughly divided into do’s and don’ts, or at least that is what ‘Curating for Dummies’ would tell you: “Try to maintain a sense of homogeneity in your installation and make sure the works can be properly seen.” Tudor ignored such advice and went for some interesting choices in presenting the visual material – he in fact resorted to quite a few curatorial don’ts, like the historically indiscriminate hanging, establishing connections between works of obviously different artistic merits, and, more strikingly, not ensuring that art works can be properly viewed. First there was a feeling of engulfing emptiness, as the largest room in the gallery had been transformed into a reading and discussion room. Works were installed with utter indifference to chronology, which emphasized the perverse continuity of propagandistic discourse, allowing for a rough thematic grouping of images into ad-hoc categories such as “mystical apparitions of the leader,” “the leader as political thinker,” “industrial achievements,” “agricultural apotheoses,” or “the contortions of history in the communist interpretation,” to name just a few. The differences in painterly skill were less important than the political significance that unified the works, denouncing them as politically homogeneous. Irrespective of distinctions between consummate master and fervent amateur, the paintings were displayed as testimonies of a political era: “good” and “bad” works in deliberate disarray drew attention to a more difficult distinction—the one between oppression and (sometimes enthusiastic) obedience. The sense of amalgamation was also enhanced by the curator’s use of the museum’s residual spaces—perfectly unfit for looking at works of art. I am referring to the narrow corridors left behind after the conversion into a gallery for contemporary art of a wing at the Palace of the Parliament, a building formerly known as the House of the People, the second largest in the world and certainly the most melancholic. With the museum occupying a mere fraction of the former forbidden city, the strategy of installing works between the original wall of the House of the People and the sheetrock wall of the museum sought to decontaminate the space. Tudor described those claustrophobic spaces as encapsulating fifteen years of post-revolutionary history, haunted by the after-images of unresolved historical questions and filled with the relics of a misconstrued past. The House of the People now hosts the two chambers of Romania’s democratic Parliament; the fact that the takeover of this obscenely triumphant symbol of communist power by the new generation of politicians was such an unproblematic move is in a sense dangerously similar to what communist propaganda would have said about the edifice. From Terminal Megalomania to Constructive Genius of the People Some heavy re-branding was involved in the process, as the House was transformed from an initial representation – the product of terminal megalomania, of a troubled mind unable to decide whether to succumb to an inferiority complex or to follow a superiority impulse – to becoming an illustration of the constructive genius of Romanians, of their mythic potential for buildings things that last. The new reading bypassed a few intractable facts for a policy of happy forgetfulness, echoing the difficulties of the institutionalization of memory in post-communist Romania. In the late 1970s and especially during the 80s, Romania was turning into a ruin and economic catastrophe caused by gigantic industrialization plans, completely indifferent to social necessity, came together with the delirium of nationalism and monarchic festivities in praise of “the most beloved son of the nation.” The cult of personality, taken to extreme by the creation in 1976 of the “Chanting Romania” festival, meant that power could completely dispense with the democratic appearance of an autonomous cultural sphere. It was no longer looking for legitimacy elsewhere than in its own violent exercise. Under such circumstances, art acquired a purely instrumental function – it embodied aesthetically totalitarian ideology and could only be judged in terms of militant efficacy. One of the essential tasks of art was to build visually the uniqueness of the leader, to singularize him, like an island in the dogmatic ocean. The historian Adrian Cioroianu describes this primitive accumulation of authority, this Stakhanovist flow of the leader’s apparitions, as videology – the tendency of an ideology to become limited to one function, that of making an effigy visible. Ceauşescu’s portrait belongs to the sphere of the miraculous, and we can only attribute to misplaced piety metaphors like “father and son of his country” or “providential son of the world.” CeauLescu’s relation to time is two-fold. On the one side we have the “uninterrupted revolutionary activity,” on the other – “eternal youth.” In the beginning of the 1980s, the iconography of Ceauşescu enters an accelerated process of multiplication, it ramifies endlessly as painters strive to create ever new backdrops for the figuration of the leader. A future museum of comparative totalitarianism could verify the hypothesis that no other figure of ideological art has produced, through the complicity of party apparatus and artists, such an abundance of avatars and has not been endowed with such a force of dissemination. To invert a trope of communist propaganda, this iconography does not have “an unshakable unity.” On the contrary, iconography gesticulates rather deliriously towards some sort of all-encompassing, pastoral Maoism. Ceauşescu’s multiple portrait is composed of apparitions on agricultural fields and in factories, between workers, soldiers, doves, medieval kings, children, architectural and industrial achievements, bears he had shot, and blossoming trees. This polymorphous portrait relies on quite a few biological and historical enigmas, on overblown facts and amputated proportions, on a mechanism of replication and mystification that proliferates without control and meaning, fueled by the zeal of painters. Most paintings choke on their own pathos, disfigured by empty, rampant agitation, ready to throw into negotiation an extra metaphor in order to persuade an undecided buyer. It really feels like a flea market for signs and symbols: a bonus dove, a sweeter child, a new twist, another child, two for the price of one. No single painting seems capable of emanating the solemnity and significance of the exercise of power. Instead of an awe-inspiring, stable stance like that of Lenin, Ceauşescu is preternaturally busy, and any canon is replaced by an explosion of actions and interjections. Thus the cult of personality acquires what it desires most: the quality of being everything, of taking everything into possession, of having its will with the order of things. Painters create this dispersal or ubiquity by multiplying their art-historical references in a way that might look like a post-modern rewriting of the history of painting, were it not something radically different. It is repetition compulsion, hidden through acts of lateral thinking, whose preferred territory is art history. Artists return from their trips dragging behind pieces of style or fragments of decoration, an activity we can understand as bricolage or simony. They resort to various styles and stylistic devices to embellish their exercise in glorification and to diversify the encomium. We see the presidential couple posing under the guise of a Trecento Annunciation (“Thanks, I already know!”), and impressionist brushstrokes systematically used to sketch applauding crowds. Impressionism is instrumentalized to convey anonymity, abstract art fills up holes in composition and meaning, and an Expressionist touch metaphorically conveys the constructive energy of the nation – these and many other traits testify to an understanding of art history as a repository of decorative formulas, where style is used to dissimulate the endless repetition of the same statement about authority and submission. All the works tend towards an unwitting Surrealist feel, and everything is indeed possible. After seeing a miniature replica of Brâncuşi’s Endless Column topped by the logotype of the Communist party, it is easy to imagine a Barry Flannagan rabbit hanging from an Alexander Calder mobile. This grotesque spectacle with art-historical props, in which the notion of style is baffled, is perhaps one of the directions in which future theoretical approaches of the paintings can proceed. (The House of the People is actually the ultimate consequence of this treatment of the notion of style as an inventory of interchangeable signifiers with no prescribed order, as it enacts a carnivalesque disorder of styles on a colossal scale.) The social and cultural ramifications of this uprooting whereby style becomes only a matter of pragmatic opportunity, the political contract between artist and leader, the complicity of artists who supply power with space for symbolic action – all these are essential in understanding a period in Romania’s recent history when the colonization of the imaginary had disastrous effects. Elevator Music The young artist Aurel Cornea was invited to do a sound installation in the elevators of the museum in the context of the show. Cornea’s The Sound of Historical Conflict was a subversive political mix in which the artist cross-faded between political speeches of different periods and motivations, yet all overflowing with the tropes of populism, as if a single political voice had been speaking throughout modern history to one dormant Romanian nation, always mesmerizing the audience and relegating it from the status of collectivity to that of crowd. The most widely-held view of Communist Romania is a vision of lonely dissidents sailing the sea of passivity and an entire nation imprisoned through the will of one man. But such a perspective isolates evil in the same manner that the paintings themselves sought to singularize the object of political devotion, creating something like a lonesome Lex Luthor, dictating in the absence of any opposition. Yet ”not everything in a Communist regime can be explained by the monopoly of a single party,” as Raymond Aron noted. The Communist image of the artist was that of spiritual guide for the masses, channeling revolutionary dialog and giving visual form to their hopes of a golden future. The paintings illustrate a different function—that of anticipating and actively creating the phantasms and fantasies of the supreme commissioner, of creating for power a world of instant visual gratification. We observe artists deposing the ravished body of art at the feet of power and we see an ideal reciprocity instead of involuntary servitude. The grand narrative of ideological, party and political brutality becomes intertwined with an infinite number of biographies, destinies consumed in the absence of any sort of collective meaning.

01.03.2005

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

|

04.02.2020 10:17

Letošní 50. ročník Art Basel přilákal celkem 93 000 návštěvníků a sběratelů z 80 zemí světa. 290 prémiových galerií představilo umělecká díla od počátku 20. století až po současnost. Hlavní sektor přehlídky, tradičně v prvním patře výstavního prostoru, představil 232 předních galerií z celého světa nabízející umění nejvyšší kvality. Veletrh ukázal vzestupný trend prodeje prostřednictvím galerií jak soukromým sbírkám, tak i institucím. Kromě hlavního veletrhu stály za návštěvu i ty přidružené: Volta, Liste a Photo Basel, k tomu doprovodné programy a výstavy v místních institucích, které kvalitou daleko přesahují hranice města tj. Kunsthalle Basel, Kunstmuseum, Tinguely muzeum nebo Fondation Beyeler.

|

New book by I.M.Jirous in English at our online bookshop.

New book by I.M.Jirous in English at our online bookshop.

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment