| Umělec magazine 2005/3 >> Psychogeography: City, Utopias and Maps | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Psychogeography: City, Utopias and MapsUmělec magazine 2005/301.03.2005 Denisa Kera | psychogeography | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

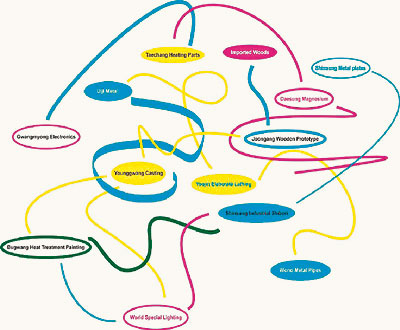

There is an apparently haphazard stain across an invitation to the vernissage of South Korean art group Flyingcity’s psychogeographic exhibition at the Display gallery in Prague that covers a map of Seoul. That spot opens space for investigation. What is the origin of the stain? Be it dramatic (blood), or purely trivial (coffee), the shape on the map demarcates and creates a new territory.

The official map of the city is overlaid with a “map” of a personal story that invites us to go on a trip and to determine what the locations connected by the stain have in common. How does the personal story overlap with the story of the city? How does one seek out the footprints of a city’s individual and collective stories? Where in the city can we find a similar stain, an incidentally created urban unit that is the result of some unknown catastrophe or a completely forgotten event? Psychogeography is a type of urban research; but it is also a form of entertainment that allows us to experience well-known places in a new way, to change the everyday routine and habits, and make the city-walk an art performance. It draws on the criticism of the functionalism and urbanism of the 1950s and 60s from the artists and thinkers of the Situationist International movement. Against unification and rationalization, psychogeography emphasizes experiments and play. The original inspiration was probably the figure of a city flaneur, as described by Walter Benjamin in his study of Charles Baudelaire; but there are also other descriptions of the city, such as that of Thomas De Quincey, or Dickens’ night walks of London. For the writers of the 19th century, the city is an important “topos” that we tend to overlook just like everything familiar and well-known. Maps and Interpretations of Reality With digital technologies, psychogeography and city experiments have come alive in recent years. The relation of the “virtual” to real space is often defined in present projects as the relation of a map to territory. The rule is that variations on maps introduce entirely new views and experience to a territory, but also a further freedom for making up and looking for new maps. Digital technology favors visualization projects that, with the help of “new” maps, modify our view of “reality.” We shouldn’t forget that maps have always served as ideological tools to identify with a given territorialization of the world, one which is never neutral, but supports various nationalistic and political aspirations. Whereas medieval maps present a world with Jerusalem and the holy church at the center, in renaissance maps—Mercator’s from 1569—the Atlantic Ocean is in the middle, reflecting the concerns of seafarers and colonizers. The Mercator projection is to this day our “own” map of the world—the one with which we orient ourselves—retaining the feeling that Europe and North America are still the center. However, their dominant location and size are distorted. The relation between map, history and territory remains similar to the relationships among language, interpretation and reality. Visualizations made possible by digital technologies open up new ways to define maps and common representations of the world that direct our orientation and actions. The aim of such playing with maps—a kind of political and art critique—is to show that no representation of the world and no technology is ever neutral—they always conceal various interests. In contrast to that, there are personal, original maps that present reality in a new and unusual way, and force us to admit the claims of groups and entities which we don’t notice in usual maps. Such is the case with Josh Ono’s They Rule (http://www.theyrule.net/), various conspiratorial maps and diagrams of the French art group Bureau d’études (http://bureaudetudes.free.fr/), the maps confronting and joining the virtual and real world in projects (http://www.logicaland.net), (http://myzel.net/geomorph, http://minitasking.com), the plural and subjective maps of various cities of the Brazilian project (http://www.lucialeao.pro.br/pluralmaps), and the Austrian project (http://futurelab.aec.at/wegzeit/). Psychogeographic Algorithms Psychogeography is the study of the creation of similar maps and the “discovering” of new territories. While the original psychogeography took to experiments with overlapping of maps of two cities or walks following a certain geometrical shape, smell or use of our senses and orientation in an unusual way, today “algorithmic” psychogeography is widespread. Similar walks use a predetermined, sometimes generative and randomly altering algorithm. Algorithms are the basis not only of digital technologies; they also govern the building of cities and functioning of society. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a functional ideal of an economy, but could include limitations presented by transportation or human habits that lead to a particular organization of space or movement in various places. These are also our individual algorithms of motion around the city—inner maps that we created to join and relate places where we work, enjoy ourselves and live. Psychogeographic algorithms aim to identify these various maps that we often aren’t aware of, and they attempt to create new detours in the city and our experiences; their purpose is to create new maps. The city in a psychogeographic walk becomes a database through which we move in various ways, choosing “data” according to new algorithms. The database is an ideal post-modern concept because it enables an unlimited shifting of data, joining unexpected patterns. If the city is a database, walking becomes software. The objective of the walk is to try the given software and to observe where it brings us, what we will see on the way and how the city appeals to us in the process, and what story and map is thus created. Various algorithms of walking are the topic of a group of people around the Social Fiction movement (www.socialfiction.org) and Dutch artist Wilfried Hou Je Bek. The aim of algorithmic psychogeography is not only to seek out hidden and strange aspects of cities, but also to discover patterns and even intelligence in seemingly chaotic phenomena. Unlike the traditional psychogeography these urban experiments don’t exploit only human experience and creativity, but they also find unexpected semblances of “non-human” intelligence and patterns of some different and unknown world. The city then seems to be a complex and intelligent being which has its purpose also outside human needs. An example of the easiest algorithm for walking would call for turning twice to the left, once to the right and then once to the left while walking through city streets. The aim is to document the unusual journey—in words and in the form of a story—in which we describe what happened, who we met and what we did on that journey. It can also take on the form of a photographic documentation in which various hidden signs (street art or just ads) are documented and a visual connection is created between them. Sound records and video and often GPS technology naturally give psychogeographic walks a new dimension. It is possible to create a new visualization that interprets our movement in the city in the form of various maps and drawings. The mixing of virtual and real-world maps and territories has no specific direction, and all creative combinations and interactions are allowed. Flying Cities In this context, the Korean Flyingcity project (www.flyingcity.org) is more traditional. The project is mainly interested in the relation of a map or visualization to social Utopia. Here, psychogeographic research endows the space with a living and human content. The goal is to transform the city in a way that would develop human interaction that transcends the urban concept. As such, this group of activists and artists from South Korea understand psychogeography as an original urban form of politically engaged art. However, they refuse the evangelical pathos and paradoxically defend the ideal of autopoetic processes. For that reason, the latent irony and their fascination with constructivism presented in their drawings (a series of diagrams of Cheonggyecheon Constructivisms presented in Prague and on their website). They would like to know something about open and self-organized society, in which the processes proceed from below, without objectives and limitations given beforehand. It is not just through their interest in urban forms of present-day social life that the group is known, but also their interventions into public space, documented on video. In addition, they organize psychogeographic workshops, even in schools—and kindergartens, from which they obtained a collection of children’s drawings. All concerned with the journey to school, each picture has its own visual style, unique perspective and different way of representation. They are mainly interested in the dynamics of the city and its inhabitants, and the way social processes mingle with architecture; these are places where the emphasis is on the potential for any system to be self-organized such that new and alternative structures can emerge outside “power.” Architecture of a place often defines the possible types of social interaction in a given space. At the same time, it is the social interactions and human activities that create the architecture. This group of people’s interest in architecture arose from autopoetic social relations found within the massive Cheonggyecheon covered market place in Seoul. The relationship of space and social activity is a question addressed not only by professional urbanists and architects, but more often by artists as well. In their projects they link city, architecture and art, and look for new interstices between the “virtual” and “real” environment, Utopia and reality, map and terrain. The goal is to create a new emergent space that enables as many changes and autopoetic processes as possible, during which a new kind of subjectivity is created—and a new society. The emergent space is no mere concept. Its potential is to demonstrate virtual worlds of computer games created for the interaction of its players themselves (often against the intention of original creators and owners) and the psychogeographic Utopia, as the Korean Drifting Producers project at the Cheonggyecheon covered market place. Autopoiesis Vs Urbanism Flyingcity’s largest project to date involves an attempt to rescue this huge covered market, which may be demolished in the modernization of the city. According to the artists, a parallel and alternative world evolved, one that has its own rules and behavioral patterns that the majority of society denounces as a black market. For the artists and activists it is an island of autopoesis and self-organization which the officials are trying to destroy with a new urban plan. That is why they decided to start an uneven match and attempt to save the alternative economy and system which this covered market created. They suggest moving the market and its economic model to a different place. The market is under a big highway. The art and activist project intends to move the whole “ecosystem” onto a stadium nearby. Just imagine taking a Prague market moving it to Strahov. To get support for their project, the artists not only involved the local seller’s and producer’s community, but also the public at large, and created a huge model explaining the function of alternative economy and world of this market in different categories than in the simple opposition – chaos and order, the legal and the illegal. Their project shows that the most important thing is not a conflict between people and city, live and inanimate, natural and artificial. Similarly, to one of the best known thinkers of the city, Lewis Mumford, crucial is the conflict between the notion of the so-called biotechnics and megatechnics, between the organic model of technology and city, which allows diversity and self-organization, and hierarchical model emphasizing the quantity and linearity. This difference Mumford elaborates with the help of two more concepts of polytechnic and monotechnic. Monotechnics, meaning the dependency and dominancy of one technology, e.g. cars, is necessarily negative and leads not only to a limitation of creativity but also to extinction. The emphasizing of one technology, technique or form of the city can result in monstrous forms. What Mumford calls megamachines make people components of a monotechnic whole with a single purpose, such as war. Mumford believed that it is possible to create an organic, miscellaneous and creative relationship between people and machines or people and the city. The utopia of bio-technical, polytechnic, hybrid and symbiotic connections which support variability, is largely filled by the alternative world of Seoul’s covered market. It is built DIY fashion, handmade with metal and other materials, which most of us consider rubbish. This production gives work to the poorest segments of the population and creates for them a possibility to survive and way to integrate into society. Moreover are these structures often interesting and original from an artistic point of view, regardless of their accessibility to the poorer people. The world of the covered market is a world outside the officially acknowledged urban and economic system, but it has one big advantage in the autopoetic organization, dynamism and diversity. That is why it is good to support it and give it its own space, just as we do with national parks or endangered species. City as Organism The atlas of the changing milieu “One Planet, Many People”, which at the beginning of June 2005 published the environmental program of the UN, shows fascinating satellite shots of the uncontrollable growth of cities in the last 30 years. The shots compare the present-day state with a picture a few decades old. The result shows ecological devastation of the planet. Shadows of grey in all photographs swallow the green or other colors. They look like unicellular organisms or some dangerous bacteria, which endanger the color balance of the surroundings (ftp://na. unep.net/UNEP/OnePlanetManyPeople/Screen_PDFs/Atlas_3-7-Urban_Screen.pdf). The cities can be viewed as a sophisticated kind of organism built of steel and concrete, which needs more and more people for its further growth and reproduction. The new life form which it represents is far from an ecological utopia of a clean and perfect nature. On the other hand it presents its own evolution, which doesn’t have to be anthropocentric. The Korean group’s concept of psychogeography is actually an investigation of this new life, similar to algorithmic psychogeography and other art projects, which emphasize the idea of autopoesis, biotechnics and similar concepts.

01.03.2005

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

|

04.02.2020 10:17

Letošní 50. ročník Art Basel přilákal celkem 93 000 návštěvníků a sběratelů z 80 zemí světa. 290 prémiových galerií představilo umělecká díla od počátku 20. století až po současnost. Hlavní sektor přehlídky, tradičně v prvním patře výstavního prostoru, představil 232 předních galerií z celého světa nabízející umění nejvyšší kvality. Veletrh ukázal vzestupný trend prodeje prostřednictvím galerií jak soukromým sbírkám, tak i institucím. Kromě hlavního veletrhu stály za návštěvu i ty přidružené: Volta, Liste a Photo Basel, k tomu doprovodné programy a výstavy v místních institucích, které kvalitou daleko přesahují hranice města tj. Kunsthalle Basel, Kunstmuseum, Tinguely muzeum nebo Fondation Beyeler.

|

New book by I.M.Jirous in English at our online bookshop.

New book by I.M.Jirous in English at our online bookshop.

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment