| Umělec magazine 2003/3 >> STRANGER IN A STRANGE LAND | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

STRANGER IN A STRANGE LANDUmělec magazine 2003/301.03.2003 Travis Jeppesen | report | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

"As Martin Zet noted in these pages some months ago, contemporary artists are increasingly forced into accepting the status of nomad in order to survive. In terms of the local art scene, the implications of this are more specific. The Western foreigners who began flocking here after the fall of communism, particularly the Americans, largely came in possession of two things: large quantities of money and artistic pretensions. The equation, then, seems obvious enough. Yet instead of investing their money in aiding the creation of a local arts infrastructure, the vast majority of these privileged foreigners chose to either drink up their creative energy and trust funds, or invest it in “safe” ventures such as restaurants and bars, or simply tired of the struggle, packed their bags and left in search of greener pastures. This is an important facet that is often missing in discussions of the current “depression” in the local art scene: namely, the fact that the vast community of Western foreigners living here is also at fault, equally if not more so than the Czechs. It’s no wonder, then, that foreign artists frequently encounter an eye-rolling dismissive attitude from Czechs when asked what their occupation is; it may have been impressive to be an American poet or artist here twelve years ago, but by now, most Czechs have figured out that “American poet in Prague” usually means “trust fund kid on extended holiday.”

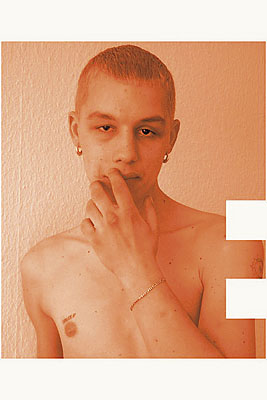

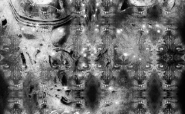

Today, there are in fact some foreign artists engaged in worthy pursuits here, although one would be hard-pressed to find any indication of this in local galleries. Unlike nearby Berlin, which boasts a truly international art community, Prague is plagued by a lack of dialogue and exchange between locals and foreigners. This is why the label “expat” has emerged as a viable identity here, whereas foreigners living in other major cities scoff at the term. The causes are usually attributed to the supposed difficulties of the Czech language, but the fact is (and this is something no one wants to admit to) there are vast differences between Czech culture and Western European/American culture — differences that tend to transpire in the form of insecurity and skepticism on both sides of the cultural divide, often interfering with and obscuring any possibilities for intercultural cooperation and development. Having lived in various American and Western European cities over the years, I can say from experience that this condition is unique to Prague. Out of fairness, I must state that this article does not purport to offer a definitive account of the current activities of foreign artists in Prague (the work of painter Bruce Linn and sound artist Thom K. Bailey are two notable exclusions here that I will have to leave to another writer, hopefully in the near future.) I will merely attempt to offer a glimpse of some of the American, Australian, and British artists whose work I’ve been following for some time, who have largely been neglected by local galleries and institutions due to some of the pre-existing conditions I’ve attempted to outline above. Perv on the run In his travels through the Czech and Slovak Republics, the British photographer who works under the pseudonym Six discovered the notorious stimulant Pervitin. Widely known throughout the country for its potency and cheap street value, the drug is virtually unknown in Western Europe and the Americas. Although he refrains from drug use himself — in fact, he doesn’t even drink alcohol — drugs have nevertheless played an integral role in the subcultural networks Six has traveled ever since his teenage years, which he spent hanging out in the London punk scene, even cohabiting with Sid Vicious for a time. While his initial curiosity was about the drug itself, Six’s interest soon shifted to a particular subcultural community in Prague among whom Pervitin plays a central role in every day life, a community that consists predominately of young male prostitutes, dealers, and thieves — for lack of a better term, the post-pubescent criminal underworld. Through befriending and later photographing these young men, Six discovered a corollary between their reckless, troubled existences and his own turbulent adolescence. “Their openness and rejection of everything their parents taught them was refreshing and was similar to how I felt when I was their age. It seems to have been lost in the West.” Six’s fascination with his subjects led to the creation of a colorized photo series, bearing as a title the ironic re-spelling PERVATEEN. Combining elements of portrait and documentary photography, Nan Goldin-esque photo realism and advertising, the thirty-six photographs are divided into four rows, each photo cut into a letter together forming the word PERVATEEN, each row of the originally black-and-white photos color-saturated according to the season they were shot — altogether comprising “a year in the life.” Furthermore, Six provides the viewer with a small biographical text for each of his chosen subjects, adding another narrativistic component that quells any delusion the observer may possess of the boys’ status as “exploited” objects. In fact, PERVATEEN refuses to view these hustlers as either victims or sexual objects, nor does it glamorize their fucked-upness a la Larry Clark; it merely shows them as they are, in varying states of inebriation, scars and all. Necronautic transploitation Last year saw the arrival of American sound artist Richard Schneider, who, in his nearly twenty-year affiliation with the project Schloss Tegal (a collaboration with M.W. Burch), is one of the leading figures in post-industrial music. Schneider’s decision to move to Prague was motivated in part by the current political situation in his native country. While employed at a newspaper in the conservative south, Schneider made some disparaging remarks about President Bush’s policies in Iraq to his colleagues; the next day, he was promptly fired. Schneider packed his bags and relocated to Prague a month later, inspired by the city’s burgeoning experimental music scene which he had encountered after performing several times at the annual Prague Industrial Festival. While he received formal training in painting and printmaking, it was in art school that Schneider first began experimenting with tape recorders and synthesizers, culminating in one of Schloss Tegal’s first live concerts in 1984 with writer William S. Burroughs and notorious noise terrorists White House. In 1990, Schloss Tegal released their first album The Soul Extinguished, compiled from two years of experimentation with four-track tapes, small Casio samplers, synthesizers, and drum machines. An eerie soundscape consisting of two parts, The Soul Extinguished laid a solid foundation for Schloss Tegal’s work in the years to come. The “music” on this album doesn’t set out to construct recognizable songs so much as it creates a disturbing atmosphere of a world located somewhere beyond the limits of human cognition via a deft utilization of the psychoactive abilities of the mind. One track, entitled “Immunde Spiritus,” is a five-minute-long opus consisting of a pulsating, echoing beat somewhere far off in the distance, the wailings of a human thighbone trumpet, an indecipherable whispered text, punctuated by a woman’s stabbing screams; the overall effect is one of entropic suspension in a sphere outside of all known spatio-temporal structures. Over the years, Schloss Tegal has explored the darker regions of the human mind, as well as various types of phenomena that may be termed, for lack of a better term, the paranormal. Their 1994 album Oranur III “The Third Report” is based on Wilhelm Reich’s theories and encounters with unidentified flying objects, and utilizes as source material “voices from space, crop circle recordings, sex and orgasms, UFO encounters, abduction experiences, cattle mutilations.” For those who tend to take these subjects lightly or in jest, Schloss Tegal go so far as to state: “Recordings on this compact disc are of an intrinsic nature true to the original source. Schloss Tegal will not be responsible for any strange or paranormal activity during the playback of these recordings.” Played at full volume in a dark or scarcely illuminated room (perhaps the ideal condition for listening to any Schloss Tegal recording), the album evokes disturbing sensations of the type of out-of-body experiences one usually only attains in states of extreme intoxication (or alien abduction.) Schloss Tegal’s highest accomplishment to date may be their creation of a complex, highly sophisticated language that is unparalleled in contemporary music. This syntactical approach, rooted in the Cartesian division of body and spirit, comes to fruition in their latest recording, the 1999 album Black Static Transmission. Consisting of eight pieces split into two tracks, entitled “Black Static Transmission” and “Tachyon Bombardment” running at around 22 minutes and 42 minutes, respectively, Black Static Transmission makes use of the EVP (Electric Voice Phenomena) recordings of paranormal investigator and musician En Llewellyn. EVP describes the process wherein voices from an unknown source are embedded into a magnetic recording tape. This field of research is used by clairvoyants and paranormalists, who believe that the voices belong to spirits of people who once lived on Earth, and who have survived physical death to go on living in another dimension that we are unable to fully access. On Black Static Transmission, voices eerily surface from scrambled frequencies of sonic deluge, mixing with a foundational surface of symphonic waves and spoken word samples taken from doomsday cults such as Marshall Applewhite’s so-called Heaven’s Gate sect. Black Static Transmission can be seen as a disturbing statement of the desire for a sort of necronautic transploitation, the yearning to tap into and actually interfere with the frequencies that constitute the Anti-World, a realm of existence where time runs backwards. As in other Schloss Tegal recordings, death and the supposed limits of human perception are constantly challenged, and the listener is transported (or “transploited”) to “a higher plane of oscillation in the cosmic spectral band that we are not able to perceive.” In addition to his Schloss Tegal activities, Schneider has recently opened a sound design studio in Prague, Synaesthetics Studios. The purpose of the studio is more commercial than Schloss Tegal, namely offering new forms of electronic music scoring, sound effects and sound design for films and video games (Schneider recently worked on the game Unreal II “The Awakening” for Legends Entertainment USA.) He is on the lookout for new projects and collaborations, so any interested parties can reach him at schlosstegal@volny.cz. Sardonic realism: it’s a wonderful lie Before we begin to attempt to understand the paintings of Jeremiah Paleček (a second-generation Czech-American recently relocated to Prague), we must first understand the mindset of a 15-year-old white heterosexual American male. We’re talking about a world that is typically structured by action movies, violent computer games, images of naked girls, and the music of Eminem — actually, it’s a world that doesn’t differ too much from the world inhabited by most 15-year-old white heterosexual Czech males. Fusing elements of pop culture with contemporary American realism, Paleček creates his paintings using images from television, video games, and movies. While his references are often evident to his audience (a recent series is dedicated to stills taken from the game Counterstrike), Paleček selects his images according to their imagistic quality — simply what sticks out to him — but also based on their narrative value. “I want my paintings to allude to a narrative but never disclose the full meaning of it. This allows the painting to be accessible to a wide variety of people, and have multiple interpretations. Plus, you’ve got to have a story with a conflict, otherwise people think it’s boring. I mean, how many times have you seen a huge group of people watching a slow-moving video that never seems to go anywhere, but everyone is still watching, waiting for something to happen?” These paintings encompass a breadth of emotions and ideas, always bordering on the ironic, but avoiding the labored self-consciousness that one finds too many instances of in contemporary American art. “I have a deep moral empathy towards the reflection of my culture. I do not wish my paintings to be viewed as ironic, but instead as embracing.” Seen through a foreign eye, it’s perhaps too easy to come to the conclusion that Paleček is merely caricaturing America. A more detailed assessment leads to the finding that Paleček is actually working in the ancient tradition of historical figurative narratives. But instead of depicting famous battles or political figures, Paleček’s gaze is directed towards “historical” subjects such as Darth Vader or internet porn models — things that are familiar to all of us, but that we wouldn’t typically consider immortalizing in art. This leads us to Paleček’s other main subject: the mundanity of suburbia. Growing up in the suburbs of a small town in North Dakota, Palecek experienced firsthand the isolation and subsequent boredom that tends to lead some young people to acts of juvenile delinquency, and others to artistic creation (or, in some cases, both.) The bulldozing of America’s natural environment outside of cities in order to make room for the building of residential neighborhoods for the middle-class, which constitutes the vast majority of the American population, is comically addressed in such droll paintings as Deer, wherein a deer has wandered into the placid scene of a housing development and seems to be transfixed by the foreignness of its surroundings, wondering where the forest has gone. By making a sort of shrine out of the detritus of American culture, Paleček succeeds in revealing the subtle mechanizations of violence lingering beneath the surface of every nonevent, while providing us with another way of seeing these same nonevents when we encounter them in our daily lives; in this respect, one could venture to say that his paintings are so intricately subtle that they’re actually quite confrontational. This holds true not only for the inanimate objects he chooses to paint, but for his human and animal subjects as well, who always seem to be just there, staring into some vast unknown and unknowable space. Inexorably (not) yours The work of Australian-born painter and poet Louis Armand infuses elements of the historical avant-garde with street art into compositions of epic proportion. A professor of critical theory at Charles University, Armand’s clear affinity for the textual apparatus becomes apparent when looking at his mixed media compositions, which tend to occur on large canvases densely layered with acrylic paints and scraps torn from magazines, newspapers, mail, and other sources. One finds in their similarity an interconnectedness that in may ways unites them all into one large, on-going work-in-progress, one that may never be completed. But that’s not the point; what’s important here is the process itself, which the painting records. With their heavy usage of fragmentation, Armand’s canvases can be viewed from a distance, although there is so much happening in them that they require detailed examination. Examining the scraps that one finds integrated into the paintings, often times painted over so that they’re only partially visible — or placed “under erasure,” the initial temptation is to be totally seduced by the image as an individual part of the whole. But when one stands at a distance, the randomness of its contribution to the overall composition allows it to retain its elemental status; that is, none of these tiny bits possess a cement of their own, ultimately relying on the composition as a whole. Everywhere one looks, the artist’s hand is present. Armand works fast, clinging hard to the impulsive moment of creation, constantly re-working the paint to avoid a flat surface until he gets frustrated and walks away. This frustration with the process of artistic creation reveals itself in the finished painting, effectively bringing to light the inherently chaotic machinations of everyday life while simultaneously commenting on an unpleasant facet of artistic creation, namely the inability to ever “finish” what one has started. Armand’s “graffiti modernism” alternately calls to mind Dada collages, geometrical abstraction, concrete poetry, Rauschenberg, Pollock, Twombly, and Basquiat, and embedded within his paintings is a critique of the gross usurpation of these artists and methods into the art historical canon, as well as a more general sociocultural reflection that is situated both in history and the present. One finds an example of Armand’s particular style of expropriation in the large-scale paintings Part One and Part Two. Here, we encounter a violent melding of media onto the canvas, a sort of dance between blood red paint, pages and pictures and advertisements ripped out of magazines, air mail envelopes, empty crossword puzzles, bits of heavy canvas and screen applied directly to the larger canvas… (Due to their texture, Armand’s paintings suffer severely in photographic reproduction.) These disparate elements of an urban environment are articulated more precisely in the second painting, wherein bluish-grey city tenements seem to vaguely emerge amidst the chaos of detritus, rising higher and higher until disappearing off the canvas. Nomad’s land We’re living in an age of cultural tourism, an art world populated by a small faithful crowd that British artist Mike Nelson has deemed “the Lonely Planet generation” for whom standard notions of home are not so apparent. At what point, then, does the cultural tourist’s gaze become significant? Fundamentally, it’s a question of perception: not only how the foreign artist perceives the local environment, but what crosses his line of perception that may go unnoticed by local artists in their daily lives. It is at this point that the postcard image fades into obscurity and something more loaded comes into the foreground. While the city of Prague is definitely not the first thing that pops into mind when considering American photographer Ahron Weiner’s recent series, it is actually the backdrop that unites them all. The method is simple: wandering the streets of Prague with camera in hand, Weiner became enraptured with the tumultuous juxtaposition of torn posters and flyers one finds emblazoned on the walls of the city, angrily competing for the viewer’s attention. Viewed from street level, these torn and weathered scraps are a nuisance, if not a harassment to the eye of the average passerby; for Weiner, who carefully selects which of these juxtapositions will work before capturing them on film as painterly compositions, they are bits and pieces that (in)form the raw matter of contemporary Prague — which are then transformed into a “whole” in the final photograph. Ad Infinitum is a “street art” removed from the streets, and is scheduled to be placed in the Guttmann Gallery of the Prague Jewish Museum, where Weiner will have his first major solo exhibition in 2005. One finds a stunning ambiguity in the composition of these bungled masses of loaded signifiers, an unearthly confusion that affects a feeling of neutrality in the viewer. These are, after all, images a Praguer is accosted by on a daily basis; despite their intended impermanence, the very fact of their omnipresence has established them as a constant fixture of the urban environment, to the extent that very few of us may even notice them; nevertheless, we are unable to consider them all, all at once. Placed within the frame, however, everything changes; we are able to consider them in a new light, shed by the outsider’s gaze; we are caustically reminded that nothing remains the same. "

01.03.2003

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment