| Umělec magazine 2003/3 >> THE SHOSHONE AND THE UNICORN | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

THE SHOSHONE AND THE UNICORNUmělec magazine 2003/301.03.2003 Radek Wohlmuth | focus | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

Artist Jan Hísek is not typically described as being unambiguous. The truth is, this is no surprise: there is

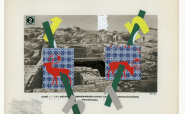

nothing unambiguous about him. He sails through the Czech art scene as mysteriously as the Flying Dutchman. He represents a special, timeless and possibly outdated phenomenon, which, however, still subconsciously attracts attention. “He’s a Shoshone [ed.— i.e. from another planet],” said Milan Salák impulsively about him. “A unicorn. The only one who carries the torch of [Czech painter Jan] Zrzavý with dignity,” as artist Vít Soukup put it. In their own way, both are right. Hísek is one of the few (one wants to say the only one) currently respected and still relatively young artists whose work carries all the signs of a distinct individual style. He is characteristic of the tradition of — in the broadest meaning — graphic expression. To date, he is the only purely graphic artist to be named a finalist for the Chalupecký Prize. The second unusual feature that characterizes his work is his peculiar but obvious link to the tradition of literary symbolism, which has led him to illustrate obscure books made only for bibliophiles. However that may be, within this dwells the most important and distinct aspect of his work — his feeling for atmosphere. Hísek falls in line with the artistic clairvoyants, of whom there are precious few. At the same time, it is just as well to call him a conceptualist. In fact, it is not easy to say where he belongs, to classify him or saying that he is a part of one generation or another. The classics often accept him, and he works easily within the “stubborn” generation from the late 1980s and early ‘90s. But when it comes down to it, he is also a friend to the trans-avant-gardists. He is at home everywhere, as much as he doesn’t belong anywhere. Hísek first made a name for himself as a graphic artist. His first important works date back to the first half of the 1990s. The year 1993 was a crucial milestone, when he left his more narrative, romantic “Tolkien” phase and continued to develop formally. Without abandoning contact with the outside world, he concentrated on the greater abstraction of the shape. Shape reduction distanced him from descriptiveness, gave his works the kind of tension that is carried within the principles of the artistic symbol. At the same time, this didn’t take away from the content, or symbolism. On the contrary, their ability to create associations seemed to go even deeper. Lyotard might even say that Hísek’s work is an angel that heralds nothing, but is the annunciation itself. The angel has no real face, and Hísek’s graphics and drawings have no heroes. The figures are only unimpassioned silhouettes, or a swarming mass, with few detailed individual features. But what Hísek takes away from the gestures and facial expressions, he puts into the space. Hísek either handles this by repeating subtle motifs, or he simply opens up the sky. This soon transformed into a condensed virtual webbing that strengthens and makes his abstract visual events dynamic. All the attention is concentrated on a hubbub of movements and multiple isochronous action. This cor- responds to the black and white interpretation of his work, which is what in fact follows on his previous chiaroscuro mezzotints. Nowadays he has moved on to charcoal, ink, pencil, pastel, tempera. Hísek’s “heaven” has quickly become an originator, a mover, a scene and the very meaning of his work. Open space, whirling and pulsing, has become a basic motif in his pictures. In spite of the picturesque expression, Hísek, with his traditional schooling and expressive habits, is still unable to deny the graphic designer in him. Although some of his pictures at first glance are a rampage of entropy, seemingly non-compositional, with no visible center or symmetry, Hísek remains partly within the arty and “over-tender” position of the Roman illuminator of the Middle Ages. He does work with gestures, with the principles of randomness and spontaneity, automatism, flowing colors, but one look at his signature in a book and the ambivalent, disturbing feeling comes back. On the one hand, he always does what he wants, so it is difficult to guess what he is going to make. On the other hand, he is easily predictable, almost transparent. What Hísek creates are not pictures in the normal sense of the word. Since 1999, Hísek has been making colorful foundations of intuition, onto which he later adds large painted linear drawings, which are often very free, though they still maintain the esthetic attraction of the arabesque — an ornament made of components bound together. Still, his often ornamental pictures, with their tendency toward sacral interpretation, are not boring. Hísek has a certain hardly definable ingredient of otherness at his disposal, and it is altogether unimportant what it should be called. This “drop of poison” is necessary and gives his works their spirit. Otherwise, our eyes would only pick out the consciousness, the ghosts, the hallucinogenic naivete or the first plane of religious agitprop. Hísek’s art is not simple. Many people are put off by it, and they have no will to follow it up. All the more because a parallel to his work is difficult to find at the moment. Hísek is first of all a traditionalist, and although his work and approaches to it are obviously developing, it is difficult to imagine that he will ever experiment with, say, video. His works can be compared to overdeveloped photographs, and in their indistinctness they transcend the limits of visual reality. Strange things are part of Hísek’s world, and he attracts them. There are not many people who I would take seriously if they told me that in the photo of him from the Macocha gorge in the Czech Republic, which has been hanging on his wall next to his door for twelve years, a white cross has appeared. Even fewer people would force me to go and take a look at it. Honestly though, never before have I gotten lost in a one-room apartment. It happened to me when I visited Honza Hísek.

01.03.2003

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment