| Zeitschrift Umělec 2004/1 >> Include Me Out - Daniela Rossell — "Ricas y Famosas" | Übersicht aller Ausgaben | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Include Me Out - Daniela Rossell — "Ricas y Famosas"Zeitschrift Umělec 2004/101.01.2004 Dunja Christochowitz | full happiness | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

“The secret codes of home are not made of conscious rules, but rather spun from unconscious habits. What characterizes the habit is the fact that one is not conscious of it. The person without a home must first consciously learn the secret codes and then forget them, to be able to immigrate into a home. However, if the code becomes conscious, then its rules turn out to be not sacred but banal.”

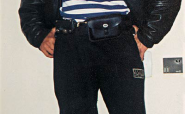

Vilem Flusser, Taking Up Residence in Homelessness, 1984 Garry Winogrand’s famous saying “I photograph to see what things look like when photographed” perfectly describes photography which synthesizes documentary and artistic approaches to the technical image. However, photography itself seems incapable of depicting habits or exposing codes, though when applied to art it does profit from the critical distance given to its motifs. The photographer/artist discloses his or her habits and consciously lays open codes not yet conceived (which are then no longer sacred). This may be what things look like when photographed. Ricas y Famosas, a series of photographs by Mexican artist Daniela Rossell, portrays Mexican middle- and upperclass women who allowed the artist into their lives and were willing to pose in what seems their natural surroundings, among their belongings, in their homes. When Rossell dropped out of the National School of Visual Arts in Mexico City, where she had been enrolled in painting, she engaged in the seven-year project. Starting with friends and acquaintances, in time she was given access to, it seems, most of Mexico’s upper-class living rooms, where no staging was ever necessary or called for. The wives and daughters (but rarely sons, as the male inhabitants of her “sets” obviously didn’t interest her too much — one exception was former President Carlos Salinas’ son Emilio, who, sitting up in a huge tree, seemingly defies his father’s notoriety as one of Mexico’s top ten most corrupt) of Mexico’s Oligarchs willingly arranged themselves amongst their belongings, merging with their property. These women never quite lose their air of dependence on their husbands and fathers. They seem innocent in their habits, mirrored in their luxury items and flush scenes of kitsch overload as they meander between colonial wannabe-grandezza and modern plush furnishings, rich with every sort of ruling class iconography selected for apparently no other reason than to display their notion of power and wealth. The background gallery of family pictures, sometimes happy family snapshots of the American graduation-vacation-holiday type, sometimes airbrushed portraits of the depicted person and/or her relatives, quickly grabs the viewer’s attention. Rossell’s photos seem to merely add yet another dimension to the already dreamy cosmos of these women’s idea of self representation. Barry Schwabsky writes in the catalogue Ricas y Famosas (Hatje Cantz): “Rossell’s subjects reveal themselves as they are or would like to believe they are, and it’s perhaps their elision of the distinction that gives the pictures the air of barely contained madness. Just as their wealth allows them to spoil themselves physically, (...), it defends them against having to face an antagonistic worldview. The idealized peasant women in drawings by Zuniga, seen in one photograph, are perfectly suited to banish any thoughts of rebellious peasants in Chiapas.” And any thought about their backward idealization of home, a strange and yet familiar medley of (Western) society’s traditional codes, the preservation and multiplication of media images and a loneliness that under no circumstances will fit into any “Golden Cage” fairy tale. Rossell states, “Most of these women live in the hair salon. They really want to look American, like what they see on TV, and they go to a lot of work to accomplish that. It’s a kind of hell. There’s so much unhappiness among the people who supposedly have everything.” Daniela Rossell herself seems to pity her models for exactly that loneliness, which she is at loss to depict in her photos, other than through abiding to the concept of home, and ignoring the banality she has just added to it. For a very brief moment, her photos surprise you with a stunning ugliness, followed by the urge to pacify, just before you dismiss them into your overcrowded mental freak pigeonhole. There may be an underlying “money can’t buy me love” claim, the boldness of their exploiters’ naiveté notwithstanding, but Rossell’s main achievement is beyond showing a contemporary version of power’s ambivalences. By introducing her series with the statement: “The following images depict actual settings. The photographic subjects are representing themselves. Any resemblance with real events is not coincidental.” She poses as a documentarian and gets caught in the mercurial effect of image-making. If anything, Rossell’s Ricas y Famosas are helpful in comprehending the artistic struggle when using photography to rearrange imagery. They may not contain too much news about “concepts of happiness” or systems of corruption, but there is something there about the relation between beauty and habit, about the challenge the photographic medium has to face when confronted by its purpose to multiply. Is it conceivable that Rossell’s photos will soon decorate the very living rooms she worked in? One easily becomes accustomed to the pictures, but it’s impossible to forget the underlying codes, so even Daniela Rossell could not forget to start anew.

01.01.2004

Empfohlene Artikel

|

|||||||||||||

Kommentar

Der Artikel ist bisher nicht kommentiert wordenNeuen Kommentar einfügen