| Umělec magazine 2010/2 >> Autopsia or On Death and Salvation | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Autopsia or On Death and SalvationUmělec magazine 2010/201.02.2010 Dejan Sretenović | The End of the Western Concept | en cs de ru |

|||||||||||||

|

Autopsia comes from nowhere. It has no place of origin nor the address. It declared itself for the first time in 1980 with fanzines Bank Rot and Prose Selavy, its biography has not been written until today, the available data about it is scarce and reduced to several published texts and reproductions. It is non-communicative, hermetic and elitist in principle, and is not concerned with the effects of its art. It has a cult status in narrow circles of fans of industrial music, it is characterized by a respectable discography, it had only two concerts and they were held at the beginning of its non-career. It exhibited its visual production only a couple of times (1987, inclusive), and then self-willingly left it over to oblivion. Its theme is Death, its method is Repetition, and its discourse is impersonal. Autopsia is autochthonous and the bastard offspring of an independent and intermedial sub-culture scene formed around ‘punk’ and ‘new wave’, but whose program and goals reach much further from the joy of ‘do-it-yourself’ production and club feasts of eruptive creativity. Accidentally or not, the emergence of Autopsia coincides with the epochal event of the death of the creator of socialist Yugoslavia, at the beginning of an ideological-institutional crisis of the Yugoslav culture–art system and the general feeling of ‘the end’ and being catapulted into the uncertainty of the ‘zero state of Being’ of the early post-socialist era. Similar to Laibach (with which it shares particular aesthetic principles and music-visual synergy), Autopsia proved to have had a good ear for the historical pregnancy of the moment and recognized in front of itself an open space for the intervention of art in the very fabric of the political economy of culture. Through its conceptually profound, theoretically cognizant, thematically exclusive and discursively intriguing projects, Autopsia situates itself beyond distinctions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture, ‘mainstream’ and ‘alternative’, imposing itself, retroactively, as one of the most authentic and most uncompromising art projects which arose within the space of former Yugoslavia during the last three decades.

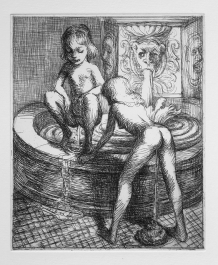

With the appearance of Autopsia at the beginning of the 1980s one should not be inclined read a close connection with a cluster of other appropriative projects (Goran Đorđević, Mladen Stilinović, Irwin) just because it operates using a similar method of re-semantization of the artistic and cultural products of the past. While these artists work inside or at the margins of the system of (visual) art, Autopsia acts outside any kind of system (including also the music scene), and positions itself as a system for itself, as an, “isolated discourse,” which stays away from any publicity and regular channels of art communication and distribution. Secondly, Autopsia does not deal with the critical reassessment of ideological normatives which condition the conception and construction of an art work, as appropriative art does; it does not discuss art by means of art, and especially does not participate in postmodern retro-practices, but imagines new–old beginnings for art (“Autopsia begins where avant-gardes end,” it is written) through returning it to its ancient cult(ural) function of the device for the ritual invocation of death. Also, the impersonality of Autopsia is not in the service of the deconstruction either of the ideology of the author nor of self-mystification (like Residents), but of its leading shibboleth, namely, to act as an information centre or an advertising agency which affects the recipient’s consciousness through a pure and depersonalized message. As stated by Vladimir Mattioni in one of his rare interpretations, Autopsia, “through method of pseudo-production, simulates standard media productions with which it gets in touch,” while establishing “the relation to production itself not as the production of something particular, but as the overall production.”1 More precisely, Autopsia has in due time conceptually digested the inexorability of the drowning of art into a hyper-aestheticized and technologized landscape of entire culture in which the production of information replaces the production of objects, and contemplation gives up its place to the instant-consummation of messages. “Autopsia stores what it destroys,” as one statement runs. Through the diagnosis of the “forgetfulness of death,” in post-industrial society as a symptom of epochal crisis of anthropological meaning, Autopsia does not return to great historical themes of death by means of typical art patterns of manipulation of signs-agents of death, but rather constructs the image as a hyperbolic emblem of death intended to the knowledge of and devotion to the reality of death. In regard to this, Autopsia announces, “There are substitute concepts only if one thinks about death as an object. Death is not something that is represented. We are mortal beings, mortality cannot be put in front of us and be observed, our own mortality cannot be shared with anyone else. This feeling cannot be ‘communicated’.”2 Bare or aestheticized, shocking or entertaining, all the same, images of death which circulate around us are essentially, “profoundly humanistic,” since they indirectly describe death and its social effects, arousing and maintaining the phantasm of death as an imaginary opposition to what is physically experienced as the reality of life. If death is a political economy of post-industrial society, monopolistically reified, processed, controlled and alienated from life, then the only way to re-evaluate it is to reverse the perspective; graphic emblems of Autopsia do not represent death, but rather it, “directly addresses,” us in the form of an aggressive-bizarre memento mori message. Images of Autopsia are rhetorical in the way in which they associate slogans such as, “our goal is death,” “death is mother of beauty,” or “I am resurrection,” with visual fragments taken over from trivial literature (technical manuals, religious press, and all sorts of other things) and in the way in which banal motives are upgraded to monster-signs of death and dehumanization. Paraphrasing Baudrillard, we may ascertain that Autopsia tends, through the, “infinitesimal injecting of death,” to bring about that kind of overcoming, or the ambivalence of understanding, of the death which will annihilate the entire play of (pseudo)values which keeps it in chains of unnatural reification. The method of repetition—recycling/montage of images and textual fragments —stands at the very centre of the operative system of Autopsia, even to the extent that it programs continuous self-quotation which causes that each work manifests itself as an “original palimpsest,” as an image which is simultaneously unique and multiple. On repetition Autopsia declares, “There is only one formal characteristic important in post-industrial art: repetition! There is no progress! There is no development! Everything is the same. Every difference is the same. New differences are repetitions of old differences. And so forth, and so on.”3 Repetition occurs in Autopsia as an obsessive reflection of the work of repetitive cultural economy in which the absence of production, concealed with the simulation of the production, stands in inverse ratio to the surplus of repetition and its commercially-manipulative effects within the control of consciousness. For Autopsia the repetition is the means through which it simultaneously wants to present the repressed presence of death (origin, meaning, time) within the structure of this economy and to transfer the observer from the state of repetitive passivity into the state of illuminative de-indoctrination—an, “alpha state,” or trance. Autopsia subliminally implicates its mission as a pseudo-religious annunciation of the archetypes of death which, un-coded as itself is, come unexpectedly and from nowhere, they self-declare themselves and multiply themselves thus testifying about the ephemeral nature and transience of everything which constitutes the (ostensible) ground of material existence of consumerist society. Inspired by the British industrial-noise music scene from the end of the 1970s (Throbbing Gristle, Psychic TV, Coil, NON) which, through the restoration of the aesthetic of a brutalistic avant-garde, “wants to liberate human mind through noise, inspiration and repetition,” (Coil). Autopsia creates the art which causes restlessness and upsets, which does not address an art lover, but the potential adept of its “apology of death.” Autopsia shares the viewpoint that technology and society are in the relation of dialectical interaction, that technology is a fact of contemporary society whose value is not measured by functionality and the innovativeness of the machine, but by the politics of governing its power to (re)produce social relations and their imaginary. “The goal of our activity is not to supplement to industrial society the experiences of some other kind, but to instruct it to find aesthetic experience within the practice of its everyday work,” says Autopsia.4 The iconography of outdated mechanical technologies (fragments of machines, technical diagrams, sights of factory facilities, and the like) metaphorically points to the fact that the machine, in its bare immediacy and isolated from the sphere of production relations, is nothing else but the specter of production which carries with itself the potency of the compulsion-to-repeat/death or, the freedom-to-repeat/aesthetic challenge. Autopsia in its work strategically uses different technologies of repetition which vary from inexpensive graphic techniques (xerox, silkscreen print), via studio-reproductive music technology (tape-loop, gramophone, rhythm-machine, sampler, non-musical devices, and the like), all the way to the use of a Spectrum computer in the realization of the verbo-voco-visual work Ikkona (an early example of computer art in Serbia). This kind of approach reflects different historical and contemporary positions of artistic techno-consciousness: the avant-garde author–producer who politicizes the way of usage of the means of production, the treatment of the studio as a meta-instrument in experimental (concrete, electronic) music, mimeographic ‘samizdat’ punk-graphics and, of course, the desktop home producer of the digital age. According to its own confession, Autopsia wants to be a, “pure art,” in constant and nomadic movement through the, “unexplored regions,” of various cultural spaces and epochs (classicism, modernism, avant-garde, pop culture, industrialism, Christianity, gnosticism, occultism) which results in a iconographical syncretistic, but semantically polytonal work of art. It is autistically-laboratorically engrossed in its own production, it dwells in self-exalted isolation, and as such it demonstrates the model of artistic behavior which is incomprehensible in the contemporary highly professionalized world of art. In other words, Autopsia is a transgression of all artistic paradigms, hierarchies and norms, the art beyond the field of art, the un-positioned and uncontrolled aesthetics of the threatening and the sublime, “the uncanny,” “the offering and the devotion, hyperbolized passion—the bow drawn towards the impossible.” Autopsia is a vivisection of the culture and the salvation of the society. Autopsia comes from nowhere… The editors would like to thank the author of the text and the Museum for Contemporary Art in Belgrade. 1 Vladimir Mattioni, “Partiturae Autopsiae”, Theoria, no. 3-4, Beograd, 1986, pp 133–136. 2 www.autopsia.net/Autopsia_pdf/Autopsia_Inter_08YU.pdf 3 “Autopsia. SMRT (je majka lepote). Razgovor”/“Autopsia. DEATH (is Mother of Beauty). Interview”/, Delo, no. 12, Beograd, 1988, pp 163–179. 4 Ibid.

01.02.2010

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

|

04.02.2020 10:17

Letošní 50. ročník Art Basel přilákal celkem 93 000 návštěvníků a sběratelů z 80 zemí světa. 290 prémiových galerií představilo umělecká díla od počátku 20. století až po současnost. Hlavní sektor přehlídky, tradičně v prvním patře výstavního prostoru, představil 232 předních galerií z celého světa nabízející umění nejvyšší kvality. Veletrh ukázal vzestupný trend prodeje prostřednictvím galerií jak soukromým sbírkám, tak i institucím. Kromě hlavního veletrhu stály za návštěvu i ty přidružené: Volta, Liste a Photo Basel, k tomu doprovodné programy a výstavy v místních institucích, které kvalitou daleko přesahují hranice města tj. Kunsthalle Basel, Kunstmuseum, Tinguely muzeum nebo Fondation Beyeler.

|

New book by I.M.Jirous in English at our online bookshop.

New book by I.M.Jirous in English at our online bookshop.

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment