| Umělec magazine 2003/3 >> BEYOND THE NEW ART OF KOSOVO | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

BEYOND THE NEW ART OF KOSOVOUmělec magazine 2003/301.03.2003 Shkelzen Maliqi | focus | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

"Experimentation and great about-faces in the international art scene are responsible for the spread of Kosovar fine arts. There is not a long tradition here in the fine arts — until recently there were only two pioneering generations of modern artists — and self-content, non-conflict academicism is dominant. The first generations of Kosovar artists (with the exception of Xhevdet Xhafa, who remained faithful to his authentic, high-quality formless art, even though it appeared here somewhat late) chose to stick to the trodden paths of figuration, concrete representation, symbolization or stylization of the “social

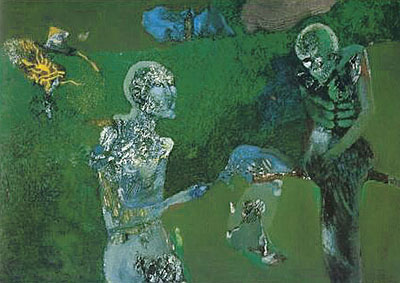

reality” and to the spirit of the times, always guided by the social environment’s predominant taste. No great experiments with techniques and genres have been undertaken. Muslim Mulliqi’s work is illustrative of this. In his work, as well as in that of the best representatives of the Kosovo school (Gjelosh Gjokaj, Rexhep Çavdarbasha, Agim Salihu, among others), themes and ideas are always clearly connected with time and space. These artists intend for their work to be representative of a particular culture. They search for something that is to be illustrative of an authentic Kosovar and Albanian fine arts. Even though their styles are different and highly individualized, it is interesting to note their thematic closeness: the circles of Albanian Legends, the traditional Albanian Towers (Kulla), the cursed Mountains and Walls that divide the Albanians, Cages, etc. The works of Muslim Mulliqi, in particular, clearly express this urge to “paint” the spiritual and ideological pulse of time, to “record” visually the ups and downs of national aspirations. There is a significant overlap between the themes he espoused during the stages of his development and the phases of Kosovo’s cultural and political development. Actually, Mulliqi’s art can be understood as a visualization of these phases. That’s why in the 1950s and 1960s (Rankovic’s era) Mulliqi began to paint in the manner of cruel social-realism. The work was artistically very powerful, but became permeated by the 1970s, a time when Kosovo was granted a high level of autonomy, with the status and powers close to that of a state. Mulliqi first produced a series depicting the Albanian Towers, symbolizing resistance, a feeling of rootedness, only to change themes for a cycle of painted blue skies, stressing the longing for the elevation of collective aspirations, likened to the flight of Icarus. Only in his last phase, in the 1980s and 1990s, when the process of abolition of Kosovo’s autonomy was initiated and brought to an end, did the artist suffer a kind of break-down of motivation. However, he made a comeback when he returned to making pure art, intimate and melancholic paintings: simple landscapes and portraits. Artistically powerful, they are reminiscent of the “eternal” and the incomparable luster of Faiyum encaustics. In any case, until the 1980s the fine arts in Kosovo flourished, while academicism represented the peak of their development. Nearly all prominent artists had established themselves as professors with their own studios and the possibility to exhibit their work. The privileges they enjoyed were not such as to arouse envy. Kosovo was a poor region, lacking a public that genuinely appreciated art. After 1981 Kosovar institutional academicism faced an imposed crises, which was to become disastrous in the 1990s. The escalation of inter-ethnic and political conflicts ruined the cultural system. In the wake of the violent annexation of Kosovo (1989–1991), the Albanians were “purged” from the educational and cultural institutions (Art Gallery in Prishtina, the Faculty of Arts, cultural centers, and a range of institutions which organized cultural life, etc.), and were then placed under the total control of Serb nationalists. The Albanian fine arts were thus either extinguished or significantly marginalized. For the next two years, the Albanian art scene was in a state of shock and depression. Only in 1993 did new alternative forms of organizing artistic life emerge, in pace with the rhythm of comprehensive self-organization within Albanian society. Restaurants, coffee shops and other independent Albanian institutions took over the role of the galleries. This art of resistance, though of varying degrees of violence, also began to question the meaning of art by adopting a critical attitude towards the art of the “fathers,” and their happy, non-conflict academicism. By the end of the 1980s a third generation of artists had appeared. They had moved away from academicism, mainly opting against “realism” in painting while embracing abstract art and experimentation. This generation reacted against the horrors surrounding them. This flight from a dreadful reality is reminiscent of the conclusion Paul Klee drew in a similar historical context half a century ago when he had said that the more dreadful the reality is, the more abstract the art becomes. The third generation of Kosovo artists (some of whom are more explicit, while others are hesitant) set out in search of new forms of expression. The bravest mastered the “destructive” and “de-constructivist” creative expression of the new post-modern art, whose credo could paradoxically be called creative nihilism. This difference between academicism and anti-academicism, as one of the possible general qualifications of this art, is stressed for the sake of contrasting the phenomenon. This frame of reference enables us to understand this art in the context of the given situation that art finds itself in. In fact, there are two frames of reference: one has to do with the local situation and artistic trends, in comparison to which this art is rather provocative. The other has to do with world trends, in relation to which this provocation appears rather harmless. But if this frame of reference is reduced only to its provocative aspect, rather than focusing on the value of the project, than its descriptive dimension and that which concerns the value may be confused. This is particularly conspicuous at the local level, where this art is perceived as being “nihilistic” and “worthless.” However, if I compare previous and current alternative art, I do not insist on the aspect which has to do with this value. This provocative art is, a priori, neither better nor worse than the previous art; first and foremost, it is completely different, and as such it requires a different sensibility and, consequently, a different approach. Regarding the second frame of reference and its relation to current world trends, I asked the following question when the exhibition Përtej was being conceptualized: “Is the emergence of the generation of young and ‘angry’ Kosovo artists only a shock of local importance? Or can they, as authentic destroyers of convention, establish wider communication with modern artistic trends in the world?” I did not try to answer to this question directly. The question was intended to provoke the visitors of the exhibition. Maksut Vezgishi’s exhibition, held in Vatra Café Gallery in Prizren (Feb. 9–23, 1993), heralded the emergence of the new Kosovo alternative art. It took place in a marginal space, out of reach of the professional audience. It went almost unnoticed, without the critical appraisal it deserved. Most likely one of the reasons art critics and artists failed to notice Vezgishi is because he is an architect by training, but he has also done work in theater (as a director, scenographer, costume designer, and so on). Only few were aware at the time that, besides furniture and graphic design, he also makes art. His theater projects were more successful, even though he mainly worked with amateur groups from Prizren. Maybe he was unlucky, or perhaps he was prevented from working on original projects with professional theater groups. In 1990, Vezgishi’s project entitled The Divine Proportions was awarded first prize at the last Yugoslav Festival of Amateur Theaters. The theme of Vezgishi’s exhibition at the Vatra Gallery focused on the new icon, with an iconoclastic tendency for a return to the symbol and to the pure picturesque, as a vision of eternity in this world. What distinguishes Vezgishi’s art is not only its spirit of universality and timelessness, but also the tendency to combine various artistic media into one project. There is an inclination in Vezgishi’s work to transcend the painting, to shift it towards other mediums of expression, always with the inclination to ontologize the picturesque in all the dimensions in which it appears, both in the formal aspects of the scene and in the reflection/image of the event. This means that Vezgishi’s performances are not concerned with stage effects and theatrics as such, or with possible illustrative and demonstrative functions of specific figurative ideas. On the contrary, he sees the performance as an extension of the painting — its outpouring into space, just as the painting itself is an extension of ideal spiritual relations. But Vezgishi was not able to fully realize these transcending extensions and shifts as he had envisioned them; these ideas were neither understood, nor did they elicit support. On the whole, his art seems to be much too ambitious to be approved of and accepted, and is even less successful in gaining institutional support in a region as poor as Kosovo, where the majority deems that there are more pressing needs to be met, and where the government has no interest in “useless” art, particularly because the goals of such art are even more sublime. Sokol Beqiri’s exhibition at the Intermedia studio in Prishtina (March 1995) represented the second important stage in the emergence of new art in Kosovo. Beqiri graduated in graphics from Pristina’s Academy of Fine Arts and completed his postgraduate studies at the academy in Ljubljana. His works were shown in several renowned exhibitions (in the Ljubljana and Zagreb biennials of graphics), and he had his own exhibition in Frankfurt am Main in 1994 (Palais Jalta). His vocation in graphics is abstract expressionism reduced to relations between white and black. Beqiri has also worked with other techniques, bravely searching for a transcendent moment in the approach, which borders on art and non-art, painting and non-painting, artifact and non-artifact, living and non-living, life and death, beauty and kitsch. The Intermedia exhibition, set up in a relatively small space in an attic, offered an interesting intersection of Beqiri’s deconstructivist research. The exhibition was conceptualized as dense reminiscence of that which could be called the roaring gallop of the artistic avant-garde of the 20th century, but presented as their mockery and parody. Parody was conspicuous at his exhibition in the restaurant The Inn of Two Roberts (Hani i Dy Robertëve) on April 1997. Here, alongside the graphics and the paintings which were deliberately provocative, “without taste,” “ugly,” done in randomly rough and incompatible colors, he also exhibited two big panels of photo-wallpaper with idyllic landscapes as a motif. However the artist had painted over them with different colored wax so that nothing remained of their “decorative,” “beautifying function, that clearly artificial expression of deceptive taste, surrogate consumption, instant beauty and kitsch.” This distance — which is irony and parody at the same time — is also discernible in the treatment and change of functions of ethnographic objects, such as windows, doors, barrels... Being old and beautiful, these ethnographic items usually impose an idolatrous and idolizing attitude — the tradition of the “folk” genius. But the artist suddenly points, using only artistic means, to their dangerous disfiguration and degeneration. To wooden barrels and churns the artist added tiny cones, thus giving them the shape of “ethno-bombs,” only to cover them with a deceptive variety of colors so that they resembled candy and looked like the kitsch that surrounds us. He portrayed the “harmless” aggression that had caused such mass destruction in Bosnia. The third important step in the emergence of alternative art in Kosovo were two successive exhibitions of Mehmet Behluli in Prishtina in January and March 1997 (Hani i Dy Robertëve and Dodona Gallery). While the first exhibition featured works representing the first three stages of his artistic research, in the Dodona Gallery he created an exhibition/installation from a complete cycle of works mostly created especially for this space. Here he chose to leave behind the monochrome abstractions he made in the early 1990s as a post-graduate in Sarajevo; instead he worked with a conceptual crossroads — configuration reduced to innocent “child-like” images on the one hand, and installations and objects representing the spatial adaptation of ideas for painting on the other hand. Yet in both cases he preserves the basic monochromatic approach in his creation of visions. He works with one dominant color (white or black, or a combination thereof), which he uses in a subtle investigation of inner movements, the pulsations of facture, compositional shapes, clashes of tone, etc. In the installations, the monochrome effect is achieved by melting tar over everyday objects, mainly old and discarded things like bags, boxes, books that are no longer in “fashion,” chairs, windows, doors, closets, old mirrors and clocks, hats and ropes, a whole assortment of transient things burnt or destroyed not only by the passage of time and inexorable entropy, but also because of mad beliefs, the desire to archive ideological fantasies, and unrealizable utopias. The tar which floods the world turns into a vision (the metaphor is obvious) of the catastrophic reality of Sarajevo, for example, where the artist lived until the out break of war, and where such spaces, rooms, piles of burned books and libraries really exist. The artist is shocked by and protests against the consequences of totalitarian ideologies, calling upon us to be cautious, not to be fooled by bogus material goods. On the whole, the alternative art in Kosovo displayed in the exhibition Përtej by the three artists (and composer Ilir Bajri), with their individual visions and approaches, reveals a political reality which is falling to pieces before our very eyes. This also concerns art, which remains intact within the iron frames of self-deceiving indifference and a worldview which is naive and illusory, as it fails to see the open pit, the abyss of civilization, the absurd, and finally the threat of general entropy. June–August, 1997 "

01.03.2003

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment