| Umělec magazine 2004/1 >> Burnt Toast and Broken Satellites: The Art of Jan Jakub Kotík | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Burnt Toast and Broken Satellites: The Art of Jan Jakub KotíkUmělec magazine 2004/101.01.2004 Travis Jeppesen | profile | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

Like a lot of young artists, 32-year-old Jan Jakub Kotík started out as a musician, playing with a number of indie rock bands in New York after finishing his art studies at the prestigious Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, where he was a student of Hans Haacke. He actually quit making art altogether for a few years after school, focusing all of his energy on music. Then he moved to Prague and made a sort of rock star comeback in 2000 with a solo exhibition at the Center for Contemporary Art. Entitled Economies of Scale, Kotík exhibited tiny household appliances intricately constructed out of model airplane and tank parts. The idea started off as a joke while Kotík was still a student, with the artist asking himself, “What if I were to use these model pieces to make a vacuum cleaner?” So Kotík made a vacuum cleaner. But he couldn’t stop at that. Like some kind of domestic Dr. Frankenstein, he returned to the store day after day, searching through boxes of plastic model parts to find the exact right pieces —“The Japanese make the best, the most detailed,” notes the artist. He not only made a vacuum cleaner, but a hair

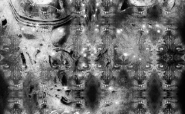

dryer, an iron, a sewing machine, a mixer, a mobile phone, a toaster, and an oven range. What started out as a joke culminated in a startling commentary on the corporations that produce these mundane household objects — the same manufacturers responsible for the development and production, in collaboration with the U.S. government, of radar technology, guided missiles, spy ware, satellites, and various other militaristic technologies employed in the wars of the last century. With a nod to the wall sculptures of Ashley Bickerton, the miniatures were displayed on white boxes unambiguously interconnected with electrical conduit, itself to become a future medium for Kotík, interestingly enough. Kotík’s most recent solo exhibition (60 Watt Max) at Galeria Estro in Padua, Italy, continues along this line of interrogation. Entitled We Bring Good Things, the artist designed four 60-watt lightbulbs meant to correspond with each facet of U.S. home appliance manufacturer General Electric’s enterprise — military, communications, consumer, and media. While the focus here is on General Electric, Philips, Braun, and Krupps are also influences. This bizarre interrogation of corporate identities forms one of the main strands that connect the seemingly disparate pieces of Kotík’s unique oeuvre into one cohesive whole, a conceptual art practice that is both accessible and reluctant to state its cause in an overt fashion, thus bowing down to contemporary notions of progress while simultaneously elevating itself to timelessness in the precision of the end product, where the exquisite detail of the artist’s execution matches brick-by-brick the fully conceived idea. Although we have to consider these pieces as “political art,” We Bring Good Things is a prime example of Kotík’s typically ambivalent stance toward his subjects; the displayed works are thus endowed with an ambiguity that give them an edge, establishing them as relics of their time. In the Shadow of the Horns Music alone, argues Kotík, has a power that art doesn’t. Since the advent of modernism and industrialization, art has progressed away from emotion, moving closer to garnering an intellectual response in the viewer. As a result, there has developed a split between art/intellect and music/emotion. Visitors to the opening exhibition of the Futura Gallery were forced to confront this issue when they were literally blasted away by Kotík’s mixed media/audio installation, Hail to the Chief. The idea came to the artist as George Bush’s administration was plotting the war in Iraq. The piece is comprised of a floor-to-ceiling stack of “Marshall” amplifiers that the artist built himself, with the American presidential emblem embroidered on the center in gold. The speakers blare a modified sample of the guitar introduction to Black Sabbath’s “Iron Man,” which is digitally manipulated to evoke the sound of air raid sirens and planes flying overhead. Heavy metal and fascism converge into a singular aural/visual invocation of the global political deity himself. The piece not only seems to be transmitting an ironic political message through its loud appropriation of national imagery, but provokes a range of contradictory emotions that the viewer is forced to confront. It’s a very maximal in-your-face work of satirical agitprop; at the same time, with its use of heavy metal symbols, it is invested with what the artist calls a “cool factor.” Art needs a cool factor in order to keep the next generation of art producers and consumers interested, argues the artist. At the same time, he adds wearily, if there’s only a cool factor and nothing else, then it’s divested of its power as art and is reduced to the status of fashion, or a commodified prop. The inherent coolness of a piece should work to obscure the underlying message somehow; in this case, the trick is done with musical iconography. War is Sexy The confrontational strain that arises in Kotík’s work is exemplified in a performance that took place in Prague’s Galerie Display on September 24, 2003. Kotík hired several Versaci models to mingle with gallery visitors while wearing t-shirts bearing slogans from the Bush administration’s so-called war against terrorism. Catch phrases such as “Axis of Evil” have burned themselves into the consciousness of nearly everyone, to the extent that they’ve become banal, nearly empty of all meaning, if there ever was any to begin with. In a further ironic gesture of capitalization, Kotík allowed visitors to purchase the t-shirts (but not the models.) The slogans of war were effectively transformed into a fashion statement. Politics aside, works like these also confront the differences between two very specific cultural forms of irony. Irony has played a vital role in the historical development of the Czech consciousness, as seen in such ancient fairy tales as “Dumb Honza,” as well as the modern archetype of Svejk. This particular mode of hero-zero mythologizing is completely alien to the American mentality. Indeed, in evaluating the recent resurgence of irony in America, one finds that it typically comes clothed in thinly veiled (pop) cultural references, adversely reducing an otherwise powerful trope to the status of empty sloganeering (an obvious example of this is the hyper-ironic American TV sitcom, unambiguously called That ‘70s Show.) These two disparate modes of irony are bridged when considering Kotík’s decision to stage this very “American” event in the Czech Republic. Seen in this light, the event becomes a critical commentary on the advent of globalization, which is essentially Americanization. The Politics of Toast Every American family owns a toaster oven. My parents even own two. I’m not sure why, but I suppose it means that they’re extra-American. In its crudest manifestation, capitalism conflates identity with buying power; i.e. you are what you own. Kotík’s work points that out to us, then further complicates the matter by refusing to comment on it. The most notorious manifestation of this strand running throughout Kotík’s oeuvre is his series of Bankomats, first exhibited as part of the Prague Biennale 2002 exhibition at House of the Stone Bell. Here, the logic of consumerism is brought to its ultimate conclusion — we are brought into some twisted vision of the future, wherein the viewer gets to choose which money dispenser best suits his/her individuality. Perhaps the different bankomats even dispense individually designed currency. (When considered from a local perspective, the bankomats take on an entirely different meaning. Kotík has speculated that he might have never returned to making art had it not been for his relocating to Prague. Although he grew up in the United States and English is his mother language, Kotík is one of a handful of Czech-American artists who have returned to their family’s native land and begun approaching local motifs from an American perspective. In the case of the bankomats, we find a young Kotík returning to his “native” soil in the midst of the late arrival of capitalism, in which the crudest aspects of the economic ideology have manifested themselves in a general attitude of crass materialism and subsequent corruption of values that is definitely unique to the post-Communist Czech state.) Jan Jakub Kotík’s work is obsessed with the inner workings, the machinations of power, and how these machinations are constantly working outside of the public eye to inform and transform the culture-at-large. When I visited America recently, it suddenly dawned on me why the country seems frozen in a disturbing moment of political apathy while its current leader wages war against defenseless countries and employs imperialistic means to reach his highly dubious goals…Why should anyone care about these things when everyone there is so comfortable, when they are surrounded by these comfortable home appliances that make life so much easier, when even those on the lowest rung of the economic tier can still afford to own a car? If you provide people with luxury items above their basic needs, items that delude them into believing in a superficial notion of progress, then it won’t disrupt their morning digestion to learn that the same company that made their toaster oven also made the missile that just killed a bunch of people overseas. Speaking of killing machines, it’s not widely known that General Electric is also one of the major subcontractors for the B-2 stealth bomber. Development of the aircraft began in the early 1980s, around the time that former actor Ronald Reagan was elected president of the United States. It was intended as one of a new breed of planes capable of avoiding radar detection. The idea was to build planes that could go deep into enemy territory without being discovered, ideal for raids on the Soviet Union or other far-off places. Since the end of the Cold War, there has been a debate in the U.S. government over the necessity of continuing to produce these planes (it costs around 1 billion dollars to make one), with the interests of corporations such as GE often influencing politicians’ motives via generous campaign contributions. Kotík’s obsessive need to communicate these little-known facts through his work is brought to the surface in pieces like B-2, a wall sculpture made of electrical conduit, and Breakfast of Champions. In the latter piece, a toaster oven was used to burn the image of the Russian satellite “Mir” on to eighty pieces of bread. (In a strange coincidence, the same day Breakfast of Champions was first exhibited in Prague Mir descended to Earth and evaporated.) Two years later, Kotík completed his most ambitious toast piece to date, using 240 pieces of white bread to toast the schematic drawing of the General Electric TF-34-100/A turbo-fan engine found on the A-10 Thunderbolt attack plane. Developed in 1975, this plane is used primarily by the United States military for close combat situations and special forces missions. Again, the viewer is forced to confront the relationship between the government/military complex and the domesticity of American life — a relationship that crystallizes in the corporate identity of General Electric. Of course, there’s no way to know these things by simply looking at the pieces. One of the more readily identifiable problems in the recent development of conceptual art is its insistent closure around the work’s message. Conceptual work often diverges into illustration of a point, where people are immediately able to identify the message being communicated, or the opposite scenario, wherein a work relies wholly on text to support its premise. Kotík manages to avoid both of these dead-ends by simply refusing to give us all the information. This approach to making art shrouds the individual works in a coat of mystery, leaving us in the end with a profound aesthetic experience and the desire to know more about these subjects. Like the satellites revolving around the Earth, Kotík has made a similar revolution with his conceptual art. He’s retired the drumsticks for now, and says he can’t imagine doing anything besides making art. He hardly listens to music anymore, instead relying on the constant buzz of information transmitted via radio and television — a buzz that is making itself more readily apparent in his recent work. Although he does intend to incorporate sound more directly in future projects, in his art he has realized a highly personal vision of the external world through his obsession with its inner workings.

01.01.2004

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment