| Umělec magazine 2003/2 >> CT 3 and the State of the Free Techno Party in CZ | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

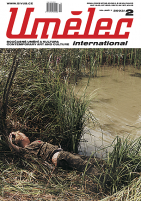

CT 3 and the State of the Free Techno Party in CZUmělec magazine 2003/201.02.2003 Milan Mikuláštík | techno | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

This year we came back from Czechtekk on Monday. After our return we had a small gathering at my home where we watched television in the expectation that there would be at least a short report about the party on the news. At first we were nicely surprised when the announcer mentioned that they would feature the festival, but then came disillusionment when we heard a load of nonsense and inaccuracies (for example, at the free parties they apparently play music reaching a speed of 120 BPM [beats per minute]. In truth they play more than twice as fast; today 120 BPM is the basis for the slower chill-out compositions).

This disinformation which the media spreads each year about Czechtekk could be seen as a tradition. How great then that the made-up reports are passed on to the print media (I also read the above-mentioned mystification a few days later in the biggest Czech daily). Of course poor journalistic work happens, but it leads one to wonder if the relevant newspapers approach other topics with the same kind of responsibility and objectivity. Nevertheless, it seems that journalists, and, indeed, all of society, have adopted a less aggressive attitude towards the techno phenomenon and to free parties in general. After all, an estimated 30,000 people attended this year’s festival. This is no longer just underground. An event drawing this many people must be taken seriously. The history of free parties, as they are known today, is relatively short. The roots of so-called dance music lie in Detroit in the first half of the 1980s. It was there that house originated, and later techno. Important influences include the hippies in the 60s and 70s, with their mobile open-air festivals, and the electronic experimenters in the 70s and 80s (Cabaret Voltaire, Kraftwerk and others). However, it was Europe that synthesized these influences, not America. At the end of the 80s the first sound systems sprang up in England. These were parties of leftwing musicians and artists, co-owners of powerful sound equipment, who organized the first independent music events. At first they were located in abandoned industrial properties and squats (especially Spiral Tribe, who later became part of the Czech scene, but also Circus Warp, Mutoid Waste Company, and Exodus...). Ravers, lovers of the fast beats, quickly arose in America too, mainly in San Francisco. Illegal dance events were held more and more often in the open air in the unpopulated countryside. This is one reason why the sound became increasingly loud; in the city this could have posed be a problem, as could the inseparable mixture of dance music and psychedelic drugs brought by the ravers to commune with nature. A free party, however, did not only mean diabolically loud music and drugs, which the mainstream media used to try and frighten decent citizens. The basic principle of this alternative culture is the rejection of parties in over-decorated clubs with high entrance fees, unbreathable air, and efforts to fleece you with shamelessly overpriced drinks, too few toilets, and where all human rights are lost if you fall into the hands of sadistic bouncers. A free party gives you the freedom to go where you want, to have fun in your own way, and, above all, the chance to actively join in the creation of a specific event as a musician, artist or performer. Also welcome are technicians, sound engineers, lorry drivers; after all, someone’s got to take care of the refreshment stand. Free techno culture is one of self-sufficiency. Its orthodox supporters more or less scorn a lifestyle that most citizens worship. Instead of sitting in front of the television after returning from work each day and allowing themselves to be passively spoon fed a diet of approved information and warmed-over entertainment, they try to organize their free time themselves. One of the first British systems was called DIY (Do It Yourself), who later issued a manifesto under this name. This in itself contains an unspoken seed of anarchism, which the system (state), of course does not welcome. In this way the island’s techno scene clashed violently with the authorities. In 1992 in Castlemorton a huge techno party took place (estimates were as high as 40,000), followed by a wave of protests by local residents, massaged by the media, and the arrest of more than a dozen members of Spiral Tribe (possibly the first English sound system). This resulted in the passing of the Criminal Justice Act into law, which banned illegal techno parties in Britain under penalty of the confiscation of all equipment. British Parliament thereby became the midwife of the Czech independent dance scene. That is to say, the members of Spiral Tribe moved their field of activity to the Czech Republic, and their ideas really caught on here. Soon systems like Mayapur, Circus Alien, and NSK were formed and illegal dance events were held in Hostomice (1994-1996), Stará Hut’ (1997-1998), Mimoň (Czechtekk 1999) Lipnice (Czechtekk 2000) and Doksy (Czechtekk 2001). A turning point was provided by last year’s Czechtekk festival in the Andělka region, which held its first legal party, pumping out a solid 50 sound systems for an audience 20,000 strong. This year’s event was even more monstrous. More than 80 walls of sound descended from every corner of Europe for an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 listeners. Furthermore, the number of crafty people there to make a quick crown more than for the music added to an indescribable social experience. To the benefit of all, the tens of thousands of hungry and thirsty people represented solid purchasing power and the inhabitants of Andělka and Ledkov (the districts where this and last years’ Czechtekk festivals were held), admitted that despite the racket the festival created, it meant a great financial gain for them. In an online conversation with the British press, the crypto-organizers of the festival, known as Docent and Zak, mentioned several offers for next year’s sites by representatives anxious to improve the state of their district budget. It is difficult to guess what this development will mean for the future of Czechtekk, but currently it appears that the techno scene is preparing for any traps. After all, in spite of its opposition towards the majority culture, the scene makes it a priority to be open to new enthusiasts. Sound system web pages are full of utopian visions and calls for changes to society through the spreading of the beliefs of the DIY movement. The fact that the latest festivals took place on legal sites speaks for itself. In recent years, organizers have also made visible effort to avoid public censure by dealing with the troublesome mound of rubbish typically left after parties. Weeks before this year’s festival all participants were emphasizing the need to tidy up afterward. One plan put into effect was to charge a token 100 crowns per car per week parking fee (drivers were given a joke sticker for their car with the logo of the fictitious television station ČT3). This money was used after the party to hire a cleaning company. Of course, most pay no entrance fee and costs are met from the sale of refreshments. Each system, apart from sound equipment, brought along a stall with food and drink, but drugs sales, almost an essential part of foreign parties, is practically non-existent in Czech systems. And systems here (with exceptions, e.g. Circus Alien) generally do not travel (the nomadic lifestyle is common in systems in southern Europe). Members are “properly” employed (mainly in computing) and go out only on weekends and in the summer, mainly around Prague, where they have a guaranteed level of attendance by fans from the city. The organizers obviously do not have the funds at their disposal to allow them to print thousands of posters and invitations like commercial festival promoters do. Participants rely on word of mouth or, more often, from special web pages (in this country www.tekway.cz). Flyers are usually printed — electronic invitations containing only information about the sound system and the time. The location of the free party is missing from the site, and instead there is a telephone number, an info line. On the day of the party a short message is left on the number’s answer phone describing the route to the venue, and hundreds of vehicles set out on the road. Obviously concealing the venue until the last moment is necessary to foil the forces of law and order. Even today when many free parties take place on legal sites, the location is only released on an info line a few hours before the start. For one thing, there is always someone with the desire to thwart the presence of drug addicts (maybe by spraying the meadow with muck), but it would also be a shame to lose the thrill of jumping into your car when it gets dark and driving through districts looking for the entrance to the right field. The systems try to find a place for the event outside inhabited areas, if possible, in order to avoid conflict with the natives. Our country, however, is fairly densely populated and one forty kilowatt sound system can be heard at a distance of ten kilometers. Therefore this year news servers were full of explosive discussion about the freedom to hold loud music events on rented land versus the right of old settlements to a quiet night’s sleep (nearly 20 inhabitants live in Ledkov u Kopidlna). The Rolling Stones concert took place on Letná in the center of Prague at the same time, disturbing the sleep of thousands of citizens but it aroused no such emotions. Techno fans simply don’t have the money to ensure the silence of public servants, and they are not friends with the fair-minded ex-president.

01.02.2003

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment