| Umělec magazine 2009/1 >> Georges Didi – Huberman: Against the Unrepresentable | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Georges Didi – Huberman: Against the UnrepresentableUmělec magazine 2009/101.01.2009 Karin Rolle | review | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

The precarious relationship between art and history is a topic explored by French philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman. In his Bilder Trotz Allem (Pictures in Spite of Everything), he sets forth an argument against the prohibition of displaying the radical inhumanity of the Shoah through visual media; against the formulation of the “unrepresentable” and against the scepticism of visual representation. He puts forward an emphatic appeal to bring history back to the picture.

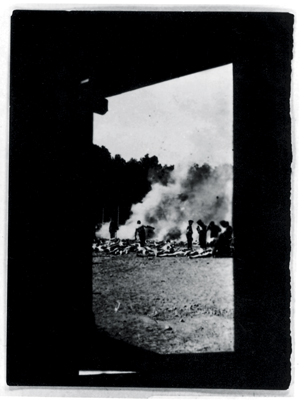

A camera hidden in the bottom of a bucket is smuggled secretly into the Auschwitz extermination camp in the summer of 1944. Alex, a Greek Jew and a member of a special unit of Jewish inmates forced to assist with the mass destruction, has taken it with him. Within a few minutes, he had completed a series of four photographs. Two exposures display the daily work of the Sonderkommandos. Under the open sky, we see cremation pits piled full. Before them, there are stacks of human corpses, clouds of smoke surrounding the cadavers. From the security of a crematorium, Alex took these pictures then turned around. Here there was yet another inferno; women, stripped naked, were being led into the gas chamber. Two blurry images were exposed. Then Alex made his way out and handed the film, hidden in a toothpaste tube, over to the Polish resistance. Seven years ago, these photographs were part of an exhibition held in Paris, Mémoire des Camps, which brought together photographs taken from inside the concentration camps. The many photos from the perpetrators, whether portraying the inmates, documenting the building of the camp, or setting down the results of the ‘medical experiments’ are juxtaposed with images from the moment of liberation and rare articulations of the victims, such as the Jewish captive Alex. These photographs have been torn from a world that the Nazis would have willed forever unseen. These camps were intended for the complete annihilation of the European Jewry. This destruction stretched far beyond the “simple murder” of the Jews; the perfidious system of the "Final Solution" hoped for an annihilation without a trace, from the cremation of the bodies, the grinding of the remaining bones, the dumping of ashes in the vicinity, and finally the destruction of the very places of destruction. In the face of military defeat, the crematoria of Auschwitz were blown up. One further intention was to make Auschwitz unrepresentable. To present the unpresentable, to salvage a trace of memory from the destruction of words and images is Georges Didi-Huberman’s aim. With his vivid description of these four photographs, and the reality that they display, he argues against a "French mentality" that cultivates a scepticism regarding representation. The unique horror of the Shoah, in this view, surpasses the forces of human imagination. Any attempt to shift this into images or words borders on banalization. Figures such as psychoanalyst Gérard Wajcman and journalist and director Claude Lanzmann argue that only a total ban on images can become a means for knowing of the Shoah. In his nine hour documentary film Shoah about the extermination camps of Aktion Reinhart, Lanzmann inserted absolutely no historical images nor historic photographs. This scepticism towards representation is a position of respect. Yet it also opens up several problematic gaps. Paradoxically, it is the champions of the unrepresentable that find themselves in dangerous proximity to the actual practice of the Nazi regime. Unwittingly, they write their own diktat for the destruction of every last trace of the European Jews. And likewise, the true Holocaust "revisionists" are beneficiaries of the image-ban: historical falsifiers such as Robert Faurisson or Udo Walendy find in the formulation of the unrepresentable a confirmation that "the Holocaust never happened." Georges Didi-Huberman presents an answer to these troubling questions; the horrors of the Shoah force human thought and the very facility of imagination to their borders. He makes reference to Hannah Arendt by adhering to the principle that we must think it through from that point where our thinking fails, that we must turn our thinking in a different direction. Standing within our guilt towards those murdered, we have to create images for ourselves. We must take up the photographs and read them, in spite of our over-saturated, market-driven image-world. Indeed, the photographs open a specific understanding; they do not allow for any all-encompassing, complete representation of the Shoah, yet they reveal “glimpses of truth” in preserving the tiny details of a complex reality. “In spite of everything, to make a picture for yourself” is the emphasazed message of Georges Didi-Huberman. The document captures with its urgency, replacing the scepticism against the image with an "ethic of the image." Georges Didi – Huberman, Bilder trotz allem. Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Paderborn 2007, 260 Pages, 29,90 Euro

01.01.2009

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

|

04.02.2020 10:17

Letošní 50. ročník Art Basel přilákal celkem 93 000 návštěvníků a sběratelů z 80 zemí světa. 290 prémiových galerií představilo umělecká díla od počátku 20. století až po současnost. Hlavní sektor přehlídky, tradičně v prvním patře výstavního prostoru, představil 232 předních galerií z celého světa nabízející umění nejvyšší kvality. Veletrh ukázal vzestupný trend prodeje prostřednictvím galerií jak soukromým sbírkám, tak i institucím. Kromě hlavního veletrhu stály za návštěvu i ty přidružené: Volta, Liste a Photo Basel, k tomu doprovodné programy a výstavy v místních institucích, které kvalitou daleko přesahují hranice města tj. Kunsthalle Basel, Kunstmuseum, Tinguely muzeum nebo Fondation Beyeler.

|

New book by I.M.Jirous in English at our online bookshop.

New book by I.M.Jirous in English at our online bookshop.

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment