|

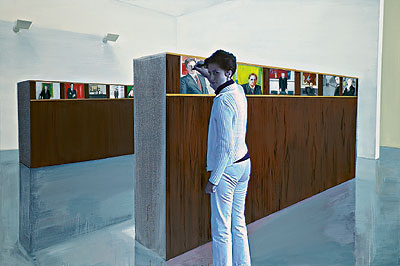

When the annual students’ exhibition of the Leipzig Academy of Arts (HGB) occured in February, it was clear to all participants that more was at stake this time than in years previous. The year 2004 had surprised (not only) the city of Leipzig with the unprecedented hype surrounding the artistic output from the German city—especially with respect to painting within the HGB milieu. In fact, so much of the work coming out of that academy had become quite the brand name that gallery owners and collectors increasingly pursued the market without any second thought. Correspondingly, market prices that had already long been paid for works by Neo Rauch skyrocketed for emerging figurative painting as well—so it’s hardly surprising that well-known figures on the scene, such as Tim Eitel, Christoph Ruckhäberle or Matthias Weischer, have broken the barrier of $20,000 per large scale job since then.Actual and self-appointed art scouts from throughout Europe recently descended on the academy, hoping to discover new bargains and new stars. But those things (with few exceptions) to be seen in the studios and in the academy hallways fell well short of expectations and gave this author frequent cause to sense sheer irony at work here: In terms of style and motif, it was all mock Rauchs, Ruckhäberls and Weischers—to such an extent, in fact, that it just couldn’t be taken seriously. Or could it? It is still an open question whether or not the media hype, generated by the likes of ART and Spiegel, surrounding what is known as the ‘Leipzig School‘ will ultimately prove beneficial to art education at the academy that has been recently so much in demand. Entering the market too early, with all the associated pressures, has led more than one artist into creative dead ends, and an overestimation of self-importance. With the surge of galleries, such as the Berlin-based artist’s gallery LIGA and the excellent Eigen+Art and Kleindienst galleries, artists carried by that wave of hype in years past have already learned to develop their own strategies against it. The extent to which this has proved effective will no doubt be revealed in their future work. Younger colleagues, however, seem somewhat exposed to and defenseless against the Leipzig label and are enjoying the attention of the floods of curators, press people and collectors coursing through the academy rooms—and frequently the considerable pressure of producing something marketable that goes along with it.Curiously, artistic content that relates in a recognizable or even critical way to social realities has played no real role in any of this hype. That may be thanks to conscious efforts by many to avoid having the label of propaganda hung on their artwork (with accompanying party approval) as had formerly been stamped on the back of Socialist Realist art. The fact that earlier representational painting from east Germany was clearly about much more than simple state-sponsored art that toed the party-line and that the Leipzig ‘neoverismus‘ of the 1960s and 70s included excellent artists whose names weren’t actively promoted such as Bernhard Heisig, Sighard Gille or Werner Tübke, may in fact technically play some role in art history reflections—but thus far, it’s been unable to substantially influence themes treated in more recent Leipzig works. An odd sort of irreality or flight into the surreal all too frequently proves the basis for this peinture pour la peinture, despite its mostly objective personage. The creation of these dallying, agoraphobic or illusory worlds cannot conceal the fact that a certain contextual void is predominant here and that a strong technical approach to the artistic medium has been emphasised. No, you won’t find anybody leaning out studio windows, lending an ear to social issues or demonstrating any other kind of commitment here. Most would probably prefer to create personal mythologies, like all those recurring offset pieces of the type that Neo Rauch ushered in. The thing is, in Rauch’s case, these pieces generally draw on only one strain of the multifaceted aspects of his artistic imagination; such interpretations tend to be quite basic, and remain superficial at best.The fact that taking a critical stance can play a reflective role in current developments in representational painting could demonstrably be seen in the example of recently deceased American artist Leon Golub. He was highly honored as an artistic conscience of the nation, though going a lifetime without the breakthrough commercial success of his abstract and pop-artist contemporaries. In order to pursue such a developmental path as a painter who relates to the human figure, a certain conscience of conviction is required, as well as the urging impetus behind it—conditions that are in little evidence in Leipzig at the moment. But shouldn’t a highly qualified technical education also allow an artist to take on a little risk at a distance from the ‘sure thing,’ or at least encourage students to do so? It’s a 1:2 probability that Neo Rauch will assume the place of prestigious instructor Arno Rink in this coming winter semester. In fact, he already delivered his tryout lecture last December. It could be quite exciting to see how Rauch attempts to instill concepts such as tradition and reality with new meaning.... In spite of all this, voices of artists such as Julia Schmidt and Verena Landau do exist on the Leipzig landscape. Even though they aren’t speaking very loudly, they are certainly expressing the right to question themselves, to address current issues and to promote objective artistry through their works. “A picture has to pose questions, otherwise I might as well be doing something else,” states Julia Schmidt in the December 2004 issue of Art. Schmidt is an artist who pushes the envelope of the medium through her fragmentary, sketchy pieces—while her successful, fellow ex-students only rarely really question the use of large formatted works in oil on canvas. And from the very outset, fellow painter Verena Landau puts herself in a position critical of capitalism itself—and though part of that economic system, she believes, one can still express a dissenting opinion. For example, when the artist sold her work and felt it publicly misinterpreted and misused by a banker after this sale, she decided to never sell her work to corporations again and made this experience the subject of a thematic cycle. A critical message and a sense of artistic delicacy were in no way mutually exclusive in this case. Fittingly, Landau is currently experimenting with societal ‘conceptions of the enemy’—and not only her own. It’s quite notable in the Leipzig circle that female artists, especially, tend to adopt critical positions much more frequently than their male colleagues do—and yet they are seemingly no less at arm’s length from the aforementioned hype than any of the others. Arno Rink, who instructs many of them, rarely neglects to mention this paradox in discussions, nor to note the absolute, equally skilled capabilities of his female graduates. This includes artist Ulrike Dornis, who’s living in Berlin these days but can fall back on her prominent Leipzig roots: her father, Kurt Dornis, was one of those earlier Leipzig artists who preferred working without much public recognition but yet have been influential for the artistic climate in Leipzig - not in the least because their conception of the object disavows lofty as well as propagandistic gestures. Along with the oeuvre of Dietrich Burger, Kurt Dornis’ unmistakeable impressions of the Leipzig industrial landscape are counted among the most underappreciated testaments of an earlier Leipzig School that generally can hardly be delineated using simple formulas. This spirit resonates in his daughter Ulrike Dornis’ work to the present day, especially in her wall-sized constructions with their formal references to steel bridgework and standard girders. Much less monumental and yet much more poetic are the compositions of Henriette Grahnert—here, too, an almost subversive and seemingly ironic reaction run counter to the usual, emblematic type of Leipzig irony. Demure color and intention-laden imperfection also characterise the canvases of Dutch-born Miriam Vlaming, who’s achieved mastery in Leipzig with her clayey, very graphically conceived lines. She’s found a thematic home employing somewhat engrossed, fairy-tale scenes and in that respect a line can be drawn, and only in that respect, to Isabelle Dutoit, whose shy-narcissitic idylls are informed by a meticulous search for creative as well as personal security, realised as a barrier between hyperrealism and abstraction.Countless excellent examples of work thriving outside the Leipzig mainstream have currently undoubtedly earned, even if only in Leipzig circles, just as much attention as the usual suspects. Moreover, much of this work merits greater attention than that of the laborious artistic imitators filling lower level art classes. Perhaps those individuals ought to try their hand at experimenting with their work and conduct their experiments of imitation away from public attention. And perhaps, one day, the pieces they produce today will be blessed with the wonderful fate of those paintings that are presently archived in the basement of the HGB. Before 1989, graduates were obligated to surrender one of their diploma pieces to their academy. Rather than allowing these fine examples of Leipzig realism, with their ultra-explicit echoes of the expressive cadences of Heisig, Rink and Gille to simply mold away down below, janitor Manfred “Louis” Tränkner now and again puts together little showings on the subterranean floors of the building. Recently, media class students of Alba d’Urbano brought some of those works back up to the top floor—to the delight and thrill of some visitors. “Just you watch,” a colleague was overheard to say, “in ten years they’ll all be painting like that again.”

Recommended articles

|

|

The editors of Umělec have decided to come up with a list of ten artists who, in our opinion, were of crucial importance for the Czech art scene in the 1990s. After long debate and the setting of criteria, we arrived at a list of names we consider significant for the local context, for the presentation of Czech art outside the country and especially for the future of art. Our criteria did not…

|

|

|

There is nothing that has not already been done in culture, squeezed or pulled inside out, blown to dust. Classical culture today is made by scum. Those working in the fine arts who make paintings are called artists. Otherwise in the backwaters and marshlands the rest of the artists are lost in search of new and ever surprising methods. They must be earthbound, casual, political, managerial,…

|

|

|

Contents of the new issue.

|

|

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment