“The author and the work are only the starting points of an analysis whose horizon is a language: there cannot be a science of Dante, Shakespeare, or Racine but only a science of discourses.” Roland Barthes

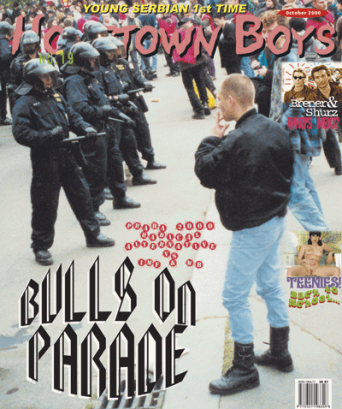

One of the major obstacles in grasping the specific discourse that Uroš Djurić uses, in order to intervene into the contemporary art scene, is his strong presence in the media as a public personality—and his charismatic appearance. When his works, especially the ones that feature images of him, are interpreted into the grammar of visual language they are easily labeled as ‘naturalistic mistakes.’ That is the mistake of equating micro histories of his personal biography, as the biography of an empirical person who is the author of certain artworks, with the narratives that make the visual content of those works and with the features of the represented characters. The mere fact that he gets engaged with popular culture both in the fields of subcultures and cultural industries (as an actor, radio host, underground punk musician), and in the field of critical and experimental visual art (as an author that is recycling samples and schematics of popular culture in his work, which is mostly figural) is easily made into a statement with his works functioning as ‘the organic representations’ of those mechanisms of cultural production and of those subcultures. ‘Naturalistic mistake’ is a result of the “generalized process affecting the whole social formation and influencing of all its activities...including the production of images.” As Norman Bryson claims, culture produces around itself a kind of a ‘habitus,’ that is constantly being naturalized, and as soon as the work of art becomes part of the culture, by being exhibited and circulated as an image, it has to undergo the same process. The whole repertoire of visual hypotheses extracted from the history of art and culture is put under experimental investigation through the composition of an artwork that comes to be taken as a subordinate to the alleged expression of one’s identity, and therefore it is limited to the asocial, privatized field of specific affiliations. In contrast to this process, the signifying practice of the artwork interacts constantly with social and political domains, raising questions of a conceptual and systematic nature. “It is about the projection of personality as a mediator of ideas,” wrote Uroš Djurić in an interview published in 1996, explaining the role of his own image in the paintings he was producing at the time, adding that the “self-portrait makes its historically determined model, with that specificity that in this case the image of the author is activated as a part of the content, by being included into the representation.” From this quote it comes to be quite clear that the image of the author is not used as a simple mirror-image of himself or of his affiliations, but as a tool for conceptual maneuvers. Therefore, Djurić appears as the ‘organic intellectual,’ in the sense of visually codifying and making more coherent, presenting and bringing into wider public existence, a specific non-hegemonic and both culturally and socially underrepresented shared world view “in a way that would be directive and organizational, i.e. educative, intellectual.” He does not do it as someone that is entering the art system from the outside, he does it as an artist fully belonging to it, and being formed by it, and thereby he is acting as a link between the life worlds of minor cultures and the art world, as it is defined in its hegemonic role. Uroš Djurić made that clear himself in discussion with local art critic and art journalist Danijela Purešević, with the following: “I use figuration like Duchamp used ready-made. I use figuration dually. And I am not a figurative painter. I am a pure conceptualist.” If one would try to name the specific territory Uroš Djurić is making these conceptual maneuvers on, it would be the tension between the ‘painterly style’ and the discourse of the work. In this sense, the ‘painterly style’ is treated as a ready-made, and that makes it possible for him to resample different historical styles without actually paying tribute either to the artists who have originally used them or to the actual times and contexts of use. He is using the surface of the painting, drawing, photograph or digital collage, as a screen for projecting not his own empirically and psychologically framed visions and desires, but those specific social issues that go far beyond what is screened in public media or is conventionally shown in major art shows. By using his image in paintings, photography, and digital collage, he produces an art of sign, an art of discourse, questioning the effects of visual images onto the usual perception of identity, history and culture, and testing the implications of use of these images onto the art system. He plays with different sets of competences for viewers – from art history to the history of media images, popular design, subcultural representations, etc, in order to catch their desire to explore issues such as autonomy and sovereignty, freedom and independence, production of new values. The subjectivity he is demonstrating in his works is already “deconstructed, taken apart, and shifted, without anchorage.” It is rooted in language and effective in a symbolic realm. It is a quite a distance from the ego and the psycho-biographic realm, which has little to do with the work, because, just as Roland Barthes has stated, the life of the author cannot be considered as “the origin of his fables, but a fable that runs concurrently with his work.” Autonomism Between February and March 1994, Uroš Djurić and Stevan Markuš published a leaflet entitled the Autonomism Manifesto that was latterly included in the catalog of their joint exhibition, held in Pančevo, in June 1995. “It was created to reduce to a minimum the eventual shallow stories about our painting,” the Manifesto’s text stated, referring to its own history of becoming, and pointing towards a new theory of subversion, as “an ability not to engage oneself in a big process of development and contribution to a general progress based on marginalization of human values and seemingly clear aims.” The Manifesto was a return to the experiences of local historical avant-gardes - namely on Zenitism, whose manifesto they are not only quoting in their own, but claim to even repeat. They were looking for a way to escape being listed among the ‘urban section’ of ‘figurative painters’ following the ‘other line’ of former Yugoslav art, that was the official ideology . They wanted histories of their own, they wanted to create the context in which the work is being produced, viewed and exhibited. Historically, (and both Uroš Djurić and Stevan Markuš were always aware of the histories of the terms they were using) the very term ‘Autonomism’ refers mainly to left-wing social and political movements which emerged in the 1960s from workerist (operaismo) roots, fighting to force changes to the organization of the system independent of the state, trade unions or political parties. Actually, their Manifesto went public around the time of the big revival of workerist discourse, firstly in political and then cultural studies, that had its peak when the Empire of Hardt and Negri outsold it’s print run and became part of the library of every left-leaning intellectual. The term ‘Autonomy’, in that new context, linked not to the ‘individual autonomy’ but to the ‘autonomy of networks’ and the power of productive synergies. Djurić very swiftly started joining different self-styled networks and initiating independent grouping of artists and art related professionals that finally resulted in the formation of the Independent Artists Association named ‘Remont,’ or ‘Repair,’ which still remains the only independent artist’s organization in the country. As Paolo Virno, perhaps at the time the leading orthodox theorist of workerism, claims, in the period of the 1990s “the poiesis has taken on numerous aspects of praxis,” which can mean that both the borders between creation and labor, and labor and politics have started collapsing. In that respect, the formation of the whole independent art scene in Serbia during the nineties could be considered, as well as a political act, aimed at opening up new horizons of imagining social ties and nexuses, as well as artistic and cultural contents and expressive modes, in an isolated mono-cultural society. Just as a remainder: the official Serbian cultural politics of the 1990s was being centered on the issues drafted by Herder in the late eighteenth century, as 1) social homogenization, 2) ethnic consolidation, and 3) intercultural seclusion. Official culture was having problems in coping with the inner complexity of contemporary cultures that it could not simply be cleansed from it. The independent art scene in nineties Belgrade was instigated as an informal and yet non-institutionalized framework for heterogeneous artistic production linked by only two major distinctions: a distance from the ruling ideological machinery and the struggle to the preservation and development of free artistic expression. It was created in a manner that made its actors and the works they were producing able to avoid any direct contact with the official scene and the value systems it was promoting. The technical term in the art historiography of the period came to be ‘active escapism,’ “the creation of a parallel fictional reality and quite personal stories which actually would not have emerged if they had not been motivated by the existential reality itself which was sometimes able to surpass fiction itself.” Active escapism drew lines of flight from the range of influence of homogenizing policies from the new ethnic national culture, and it was providing the wide community of artists with a space that was safeguarded from any type of political abuse. Paradoxical as it might seem, belonging to that scene was providing a certain sense of security that was lost from the very start of the process of normalization. Simply belonging to it was a radical statement of dissent. Rethinking the manner in which that independent scene was formed and fashioned, one could easily come to the conclusion that its formation was being at least inspired, if not led, by autonomist principles. Forming an autonomous body within that autonomous body, Uroš Djurić and Stevan Markuš were taking to the very limits its logic of ‘symbolic differentiation.’ They were bringing to it what they have been calling ‘the personal principle,’ which was fully visually materializing “author’s experience such as confessions, fantasies, frustrations, dreams, acquaintances, intellect and the author himself as the central figure of these contents.” Territory of artistic work was in that respect for them treated as a fully sovereign one, a locus of power that could never be sustained in real-life worlds. On the level of production and display of artworks, their activities were always resistant. They were resisting both the prevalent trend of the naïve ‘restoration of the picture,’ as advocated by the representatives of the state supported scene, as well as to the formalist and neo-modernist manner of painting, in which abstraction was normative, figuration almost banned and limited in its references and manners of use, in order to assure the pureness of the product. As to the former, they were fully allying with the rest of the independent art scene, but as to the latter, they were testing its theoretical limits and limitations and its ability to accommodate difference. In the setting that was being defined almost completely with the slogan ‘Modernism after Postmodernism’ , they were stating, as if quoting Bruno Latour, that since “we have never been modern,” we cannot ever be modern again . Their point was the struggle for the autonomy of the use of the language of art, and not the autonomy of the artistic work as such, which was then the matter of dispute with the bearers of locally new paradigms of neo-modernism. By the art critics and art historians of the times, Uroš Djurić and Stevan Markuš have been labeled to be part of the practice of ‘monumental intimism,’ and placed amongst the authors active in the “interspace: between the high art and underground,” with Djile Marković and Zoran Marinković, in close proximity with authors Daniel Glid and Jasmina Kalic, but even on that level their positioning was quite peculiar. Their use of image was far more conceptual and therefore denaturalized than those of any of the artists that were mentioned to be stylistically close to them, while their relationship to the ‘underground’ was on the level of repetition of visual samples that were part of the imagery of empowerment, but in a context that was not part of a subculture. What they were dealing with were mainly rhetorical operations with the language of art that were mainly paintings of conventional format completed in conventional techniques (mainly oil on canvas), and were treated as such. “We are classics,” they used to say, in quite an ironical manner - they were still students. Populism From the late nineties, Uroš Djurić started exhibiting without Stevan Markuš. He changed his preferred artistic techniques from oil painting and charcoal drawings to electronic collages, photos, performances, and whatever else might work as the most appropriate medium for the realization of various projects. He has kept passionate attachments to self-portraits and his own image has still played the ‘theoretical object’ in most works, but both the process and the final result were left much more open to respect the way of realization of that before. On the other hand, the survey of the origins of social and cultural uses of populism became more present in his work then autonomism. One can even say that his major project from the late nineties, and the most frequently exhibited project in the last few years, was the Populist Project. As the artist has stated himself, the main issue of the project is to show the interactions between the star system and identity, as its components titles illuminate: God Loves the Dreams of Serbian Artists, Celebrities, Hometown Boys and Pioneers. In the first segment of the project, the image of the artist is present in the photographs of the most famed soccer teams in Europe, but not as a digitally manipulation, or classical photo montage, it is a material trace of a performance that has integrated him for a limited time into each team, and at the same time a phantasm has been realized, staged in empirical reality and turned into a piece of work. The second segment also shows the image of the artist in different settings and periods, in the company of public personalities (athletes, pop-stars, politicians, and other celebrities), sometimes in the manner of fan photos, sometimes as paparazzi photos. In the third segment, one can browse covers of an imaginary magazine, entitled Hometown Boys, as a composite product announcing a mix of sociology and fashion, art and pornography, theory and gossip. Finally, the fourth segment brings about the most prominent artists in the field of art production and interpretation from Eastern Europe, proudly photographed wearing a red pioneer scarf in a glorious posture adopted from the iconography of socialist realism and public mediums of the former East. In this period, Uroš Djurić goes among the people, real people, not only the art crowd, and he faces contemporary society as the society of spectacle, in which art has to compete all the time with the visual power of a sport game, omnipresence of pornography on the internet and obscenity of televised militainment industries. If “spectacle isn’t a collection of images, but a social relation between the individuals, mediated through images” as Debord claimed back in the sixties, these relations can nowadays be brought back to their human dimension almost only by the mediation of art. The art of Uroš Djurić attempts to do so. From the study of Nebojša Popov under the title: Serbian Populism: From Marginal to Dominant Phenomenon, published in 1993 , to the text written a decade later by Vladimir Marković on the ideology of the Otpor movement, which claimed to represent populism without populism, left-wing scholars in Serbia were dealing with the issue of populism as determined to serve the right-wing ideology. Inheriting the elitist background of the social writers from the dissident times and simply reproducing it, they have completely missed the point that populism has no pre-articulated social implication. Their standpoint has prevented them from seeing, as Laclau wrote, “why it is possible to call Hitler, Mao and Peron simultaneously populist.” According to him, it is “not because the social bases of their movements were similar; not because their ideologies expressed the same class interests, but because popular interpellations appear in the ideological discourses of all of them, presented in the form of antagonism and not just as difference.” This antagonistic potential is one of the key sources Uroš Djurić draws on, and it connects his populist project with the roots of the populist anarchism, which has been locally reappearing from the grass-roots. His theory of populism, as articulated through his populist project, counters the prevalent left-liberal dissident humanistic elitism, taking culture to mean attitudes, values and mentalities, as they are expressed, embodied and symbolized in artifacts, performances and the practices of everyday life, so it is not only classical culture that is used in the educational sense. On the other hand, he tries to save the layers of popular culture from being leveled down. In his previous phase he was dealing with the autonomous status of artistic practice, of artistic production as such and the position of the artist in the cultural, social and general public realm, to cover also the production of popular culture. It means that he is trying to, by the mediation of artworks, save the public sphere being covered by the cultural industry, on one hand, and becoming full of epiphenomena of cultural policies, institutional programs, preferences of the audiences, normative expectations of the critics and theoreticians, etc. “It is necessary that the artist leaves his romantic image and becomes an active person between other people, acquainted with contemporary technology, materials and methods of work, and, without leaving his inborn aesthetic sense, to answer modestly and competently the questions that might be posed to him by his fellow men,” wrote Bruno Munari in his book Art as Kraft (1960). That very sentence was later used as his leading statement in 1974 at his solo exhibition in the Student Cultural Center Gallery in Belgrade. Munari, who was at the time among the most important proponents of what was named the Second futurism, displayed his works in Belgrade at the golden period of the SKC Gallery, when it’s program was being based on projects and interventions of ‘resident’ artists such as Marina Abramović, Raša Todosijević and Braco Dimitrijević, and a number of their foreign guests, such as Joseph Beys, John Baldessari, Vito Acconci, and Michelangelo Pistoletto. From the mid- to late seventies, these artists linked to SKC were creating a radical and challenging climate, as well as highly conceptualized experiments, that during the eighties spread further into the fields of photography, video, theatrical and musical performances, and even popular music with the upcoming new wave, punk and industrial genres. When I see works from the Populist Project by Uroš Djurić, especially his Hometown Boys series, I cannot resist to recall the dictum of Munari whose presence in that context did not have any direct influence, but did contribute to the state of affairs where interventions into art fields and culture with strong conceptual background were possible, and paved way for artists such as Uroš Djurić.

1.gif.thumb.png)

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment