| Umělec magazine 2008/1 >> The Myth of the Art World | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

The Myth of the Art WorldUmělec magazine 2008/101.01.2008 Ivan Mečl | catalogue | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

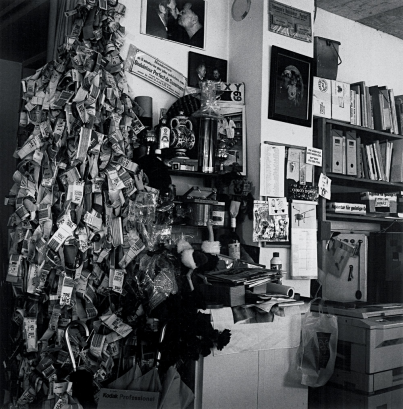

Since the time that art became a field, a system, and enterprise,

I keep asking myself, is there a way out of it all? Although the exhibition a Berlin’s Feinkost gallery sported the seemingly scholarly title, "Art World," it was neither an educational exhibit of great masters nor any basis for their inspiration. Today, the sound of the expression itself, "art world," brings to mind the sound of champagne glasses clinking, the aroma of fancy hors d’oeuvres and women who float around in the company of confident men, exchanging a few polite words here and there, but most of all, chatting about big money. The art world, alongside new technologies, is the market’s fastest-growing target for investment. This situation recalls the “dot com” boom of the 1990s, which ended up in market collapse. Much like in the dot com era, banks, corporations, small companies and individual (private) investors are all getting involved. Of course, this only applies to truly rich countries—not those who are bluffing, who are playing their hand at the art world game but who are rarely affected by booms and busts. In less-developed regions, art remains a romantic platform. The art world, sometimes called the contemporary art world, has become an expert field with its own rules and constants, its own operating space and economic possibilities. Just as a media empire was once forged, so too is an art empire now being built. The art world is no longer a world of scattered individuals bound by their feelings, tastes or alleged geniality; it has world centers where it is necessary to present oneself and host important events. It has created a wide range of positions and professions that, just a few decades ago, had never been dreamt of—and whose qualities could thrust a layman into despair. One accesses the art world as if boarding a train: tickets are avaiilable to anyone. But the ride is well worth it. Much to the good fortune of those associated with the "Art World" exhibit, the media didn’t pay much attention to the event—probably because the art world produces more than just visual art. There were more than paintings to been seen. Some works served as evidence of the empire’s serious lapses. No big investigation took place. Yet, a few small features hinted at the subtle processes that lurk hidden from the eye of the typical viewer. New heroes Harald Szeemann predicts that Balthasar Burkhard’s series of black-and-white photographs titled Fabrica will make history. His is a successful posthumous documentary from the apartment of a curator whose exhibition projects have taken a larger place in history than the artists they showcased. The history of contemporary art, whose beginnings date back to the early 1980s, will no longer focus on artists, but rather on curators. Whether we like it or not, this will actually help to make sense of the history of contemporary art, where benchmarks have swelled into the hundreds over the past 20 years. Theoretical texts already often include their author’s cultural and political positions, references to other important curatorial activities, and quotes from these events’ accompanying texts. The focus of these texts is not on the artists, but on the environments in which they create. And the sponsors of these environments are curators and critics. As concerns the fate of the stage and episodic actors, today’s artists suffer no frustrations. They simply wait patiently for their similar works to catch on, and for curators to choose the most suitable and best of their goods. Like a guardian angel, the curator then breathes life into them through eventual texts in an exhibition catalogue, or through accompanying materials bearing the artist’s name. Artists trust curators because they have ceased to believe in themselves. They have saddled curators with the responsibility for communicating their works to the viewer. But this passivity on their behalf has made possible a significant evolutionary development: by combining a conceptual artist, a critic and a strategist in one person, a curator is born. The curator then takes the artist’s position in the art hierarchy, and forms their own cult. Books similar to those that dissect in detail the lives of Malevich or Beuys will, several years from now, be written about Szeemann and his fellows. This is a natural development and it makes no sense to fight it. Today, comic strips and ironic performances on this topic abound. After all, the curator has won the fight for supremacy, but maintains enough common sense not to shout it out loud. Even if a curator does not happen to notice an artist, that artist can help himself by using the curator’s name. Works by Charles Gute, which are abstract compositions modeled on interviews with Hans Ulrich Obrist, provide one example. After removing the original text, only a map of edits and changes remained. The aesthetic result is acceptable, but without the connection to the famous curator, it would most likely not have been given an important spot in a gallery. Gute often uses the well-known name of Obrist and those of others in his creations. We can only hope that he will find his own place in these curators’ memoirs and not end up forgotten in a couple of years. Wallowing in the forgotten annals of history At the "Art World" exhibit, objects were presented without assessment of artistic value. Perhaps it is by virtue of being displayed that they become art-worthy. At issue is evidence of falsification, of cover-ups, and of pointing out possible frauds. We still aren’t completely used to the fact that both State and foundation-run museums sell art as well as display it. This could come as a surprise for some people, but most of these institutions boast about the lists of their purchases. As early as 1999, at the "Museum as Muse" exhibition, conceptual artist Michael Asher presented an exhaustive list of works that he got rid of between 1929 and 1998 by dividing the paintings and sculptures of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. A trainee prepared the material and it was reviewed by museum employees. However, when the work was exhibited, the chief curator of the aforementioned department made an excited statement whereby he attempted to cast doubt on the authenticity of the artworks sold, and the criteria for their cataloguing. Yet he himself had no information more credible than that which he had criticized. Today, that episode is almost forgotten. But for the "Art World" exhibit, it meant that it’s (already shoddy) catalogue was thoroughly picked apart. Collectors are often contacted by dealers, who woo them with their good contacts to the depositories of large art institutions. Lists of sold or even only discarded art works should become a required part of all annual reports from art institutions, whose purchases are supported by financing from either public or collective resources. This would bring an end to the corrupt sale of works below their value to private collections. It would also prevent the unpunished dumping of huge, erroneous purchases, and expert commissions would be forced to acknowledge what they are delegating as history’s forgotten works. There are so many works by deceased artists at auctions and in gallery offerings that it seems as if the artists were still alive somewhere in underground print shops, foundries and presses, rolling out increasingly worse copies of their original ideas. Among the risks attached to such below-the-belt production is the discovery of the originals’ emptiness: Dali’s statuettes, Warhol’s silk-screens, or the wooden and iron discoveries of Beuys. Today, only a person with a rural pastor’s passion for holy relics would buy such works. In the art world, strategically-thinking administrators of remains or spiritual heritage ward against such desecration by presenting certificates. However, in a desire to keep prices pegged high – specifically for those works that they own/are selling/are otherwise fond of – the administrators often refuse to issue certificates even for works that are obviously authentic. For example, the fabric pictures of Alighieri Boetti appear to have been woven by women in Afghanistan, following his model. Due to local political changes in the 1980s, manufacture was moved to Europe in order to avoid supply failures for galleries and subsequent losses in profit. After his death, this strategy perplexed his works’ collectors. But before long, a foundation in his name began to issue certificates for the works. The exhibition includes two woven pictures with framed letters from the director of the Boetti Archive stating that the works cannot be verified as originals. And so the certificate for a hand-signed and document-verified work was not issued. Were such a certificate issued, the works’ value would have increased to an amount of 25,000 EUR. Without certificates they are, according to the foundation and dealers, worthless. Nobody knows how the works with certificates differ. Perhaps they are not signed. Only good words about the dead It is healthy in any powerful country to hold reservations regarding the independence of media and the accuracy of information. But rarely are there similar debates on cultural media. After all, there’s “nothing at stake.” And even if we are talking about the cementing of political positions in the area of culture—apportioning influence between public and private institutions, and money too—no one’s life is threatened. Should you not experience culture both ecstatically and transcendentally, like some literary or film hero, the image you receive then becomes a rather dull joke. With this dull landscape it’s simple: culture has been considered a tool to cultivate man for so long that it has become a funeral parlor for all that it has absorbed. Large museum culture is accompanied by a flurry of eulogies. Their content is known only to their authors, and is not meant for living persons. Who monitors the obituaries and the widowers associations? Dead (artists)? —No. It is the artists of eulogies themselves (curators and art theoreticians), cemetery owners and administrators (gallery managers and employees of cultural institutions), and some funeral home directors (actors at ministries and corporate fund managers) as well. Some friends and descendents of the dead also give the process legitimacy, even though they have no idea that death occurred only to suit the purposes of the funeral industry. Information on death usually makes its way into normal media only when the bones are sold at a high price, or in case the funeral homes set up a large viewing of urns and tombstones, featuring an extravagant party in honor of those present, who have already been dead for quite some time. Thanks to their marginality, artistic media can play many not-so-nice games that aren’t normally allowed. It has long since stopped being necessary to take the editor or publisher aside and to offer a paid advertisement in exchange for a related article in the medium’s commentary section. The tie-in between certain larger advertising campaigns and later editorial references is sometimes excessively obvious. An editorial staff often receives pre-formulated commentaries that the advertisers assembled themselves for artistic reviews together with offers for cooperation. Therefore some artistic media don’t need permanent writers. The list of journalists in the masthead is just a who’s who of well known figures in the art world. Thanks to some international ad campaigns it can sometimes seem that art outside of the big exhibitions in rich, mainstream galleries and institutions doesn’t even merit discussion. Matthieu Laurette pointed at this phenomenon in the "Art World" exhibit simply by laying next to each other the summer issue of two magazines—the English publication Frieze and the American one, Artforum. Both magazines’ covers featured the same motif from a set of promotional photographs for one of the most expensive art shows. The Italian magazine Flash Art goes even further in its art trading. Giancarlo Politi guessed his fate in the humorous ad, printed in 1972, that read: “Today everyone talks dollars and I cost only one-thousand. I'm Giancarlo Politi, editor of Flash Art and Heute Kunst. I love women, money, success. And Art too. So I'm at your service. Services for the price of 1 000 dollars: texts, advice, opinions, debates, conferences, introductions. For artists, galleries, museums, universities, public and private institutions. Special arrangements for really good looking female artists. One condition only: payment in advance. Utmost speed and professionalism.” Next to this page in the magazine there stands a Flash Art cover that features a page from an unpublished catalogue from the Flash Art Museum collection in Trevi, and Sotheby’s sale catalogue. Both feature the same work of art. By publishing information in this sequence, one can adequately support an increase in the auction price of a given work. People have always fought to be on the covers of magazines and catalogues. Provided the exhibition sponsor is also a lender of certain works, they would of course be glad to see them in some visible place. Owners of works of art, who have a deciding role in media that impacts the art trade, have a decided advantage. Who is the owner? Who is selling the work? And why is it featured on the cover of a prestigious magazine? These are all the kinds of questions that a curator asks when they exhibit an exemplary case. This is a common story. An absurd moment in this game is the non-existent catalogue of a museum, about which no one can prove or refute its existence. The internet and various other representative portfolios that contain only individual pages of supposed publications have become popular tools for embellishing reality. Complete, online magazines pretending to be print ones and virtual institutions pretending to exist in real offices are commonplace. During the past decade, it has been possible to unify the interests of trading art with the needs of the most important cultural media. The resulting situation still awaits completion of a detailed analysis. The basis for codifying the evolution of art over the past several decades is, in present times, financial valuation. Should we not wish to lie to ourselves that this isn’t so or bemoan how business distorts reality, then we should succumb to writing the history of art based on economic success. It’s candid, simple and ultimately truthful. Any other applied theory would be a distortion. Attempting the impossible Prices at which contemporary art works are sold are most often determined by the the price for which similar works are sold at auction. At the "Art World" show, the columns of names listed are those of bidders, whom Josh Baer, publisher of the directory The Baer Faxt, has met at auctions, and those of art dealers. From his partisan position, Baer enjoys saying that which not even an independent journalist could. This time he has “exposed” a very prolific but relatively unknown abuse in the form of maintaining artificially high prices. Important dealers personally (via planted intermediaries or completely anonymous telephone calls) bid at auctions. They don’t buy themselves, sometimes the work does not even belong to them, and sometimes the work in question is of very dubious quality. Often they represent the artist being sold or have already sold a number of that artist’s works. Art traders have a vested interest in distorting the facts and it’s hard to begrudge them that. Trading is a combination of strategy and math. A model trader has a strategy based on securing guaranteed earnings and a safe level of creative risk. This is difficult even when dealing with very traditional commodities, and math often calculates losses. It is almost impossible in the case of trading the works of living or recently deceased artists. If the trader wants to treat art as a commodity, then they must attempt to regulate and influence the art world. Collectors hold art traders responsible for keeping an artist on the market. So traders need for artists to die famous, or to allow the collector to substantiate falls in bidding prices. The art trader must also make sure that artists’ works constantly maintain their price or increase in value. He must prevent the exposure of an artist’s inability to no longer create art at all cost. He must present bad works as good ones. Fortunately he has enough resources to do so—mainly financial ones. He can pay curators to support exhibitions, he can pay theoreticians to write wonderful, expert texts. He can provide financial support for an exhibition, or for an artist’s participation in an exhibition in a prestigious institution, specifically one that the artist could not otherwise attend for financial reasons. There are, after all, a number of institutions that will gladly organize any event so long as the funding does not come out of their own accounts. Ben Gavin explores this scenario in his work titled Courtesy of... : the magic phrase in official descriptions that satisfies owners but that is a nightmare for journalists and curators’ assistants. The work is based on a long list of art dealers, who are mentioned in descriptions at exhibitions and in not-for-profit institutions. So it is clear where to go in order to buy art and create profit. The number of collectors also does not grow as fast as the number of artists and the amount of art. To keep a price at a certain level means also keeping a manageable amount of art in the public conscience. This is not always possible, because certain grant programs enable the proliferation of whatever can be validated in written form. Traders represent increasingly large numbers of artists so that their offer includes a maximum amount of possible genres. Exhibition periods are shortened to two and sometimes even one week. Gallery spaces are overflowing with art, and because it is impossible to convince artists to destroy their un-sellable works, there are often desperate attempts to reorganize depositories. These attempts often end with desperate pleas to artists, begging them to store their works at their own premises. No commercial gallery space can afford to look like a storage site for used and non-sellable goods. One solution is to create new, cheap storage space on the outskirts of towns. So art also plays a role in devaluing the landscape. As a result, what were once unique creations have morphed into industrial segments, and so it is impossible to maintain their prices over the long-term. They try to meet the expectations of viewers, customers, and make a name for themselves on the market. And as quickly as possible. Does the owner of an old couch that was once really beautiful regret the fact that he did not sell it for more than he paid? Why should art that was created in a similar way be any different? Tulips. The end would be too poetic. Economists in the US and Great Britain compare the massive contemporary investments of late with the "dot-com bubble" of the 1990s. Experts unanimously expect the bubble to burst any day now, and currently inflated prices to implode. But very few of them realize that these prices were never really based on reality, and that they stem first and foremost from the charismatic talents of sellers and the convictions of buyers regardless of their own artistic taste. The liquidation of all shares in worthless companies is a pragmatic decision; but to try and get rid of artistic works at a price of one-tenth of their original value is for many an admission of their own stupidity. Most collectors therefore prefer to keep the art and just buy more. As such the bubble will never burst. But what's more: bad art history will be written. Already now, it is better to avoid any thick book whose title begins with the word “history” and which focuses on developments during the second half of the 20th century. And by the way, don’t believe any of these financial assessments of art; they are often based on a lack of awareness of any external factors. If you don’t want art to disappoint you, then don’t consider it an investment. If you've got the cash to purchase art, then buy it because it gives you joy. That should be reason enough.

01.01.2008

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment