| Umělec magazine 2008/1 >> Who’s Afraid of Motherhood? | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Who’s Afraid of Motherhood?Umělec magazine 2008/101.01.2008 Zuzana Štefková | birthing pains | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

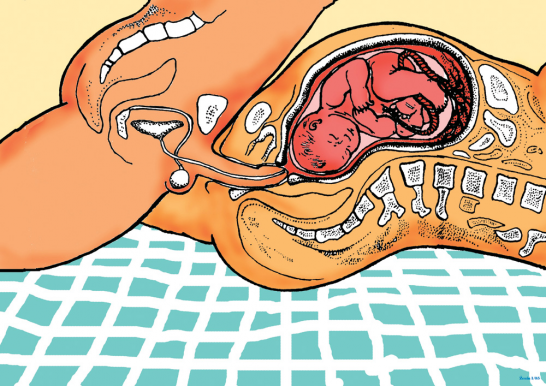

Expanding the definition of “mother” is also a space for reducing pressure and for potential liberation.1

Carol Stabile The year was 2003, and in the deep forests of Lapák in the Kladno area, a woman in the later phase of pregnancy stopped along the path. As part of the “Artists in the Woods” exhibit, passers-by could catch a glimpse of her round belly, which she exposed especially for them in an exhibitionist gesture. Indeed, it was this performance by Lenka Klodová—Bojíte se mateřství? (Are You Afraid of Motherhood?)—that led me to write this article. A pair of exhibits entitled “Umění porodit” (The Art of Birth) has served to make the theme of pregnancy more visible in recent times. The first exhibit took place in the Portheimka Villa in 2006, and the second a year later at the Prague National Gallery's Veletržní palác. Unfortunately the exhibits could not escape a certain degree of streamlining, and some qualitative compromises had to be made as well. In their book, "Pregnant Pictures," the authors Sandra Matthews and Laura Wexler emphasize that image portrayals of pregnancy often had “an extremely limited, idealized and ahistorical character,”2 and unfortunately that’s exactly how one could characterize the larger part of the works presented in “Umění porodit.” Stomachs (pregnant ones), fetuses and births dominated the vast majority of both exhibits, and all of them were stripped of any social context whatsoever. But there were a few exceptions. We are talking here about stylized actors “taking part in the grand mystery of how life begins.”3 Thus both pregnancy and motherhood were reduced to a number of physiological phases, or else they were completely removed of all substance and became abstract, symbolic compositions. Among the honorable exceptions that avoided physiological literalness and broad abstractions belong, on the one hand, to images that use parody and liberating humor, and on the other hand, to pictures that have been stripped of the psychological reality of motherhood. Minna Pyyhkälä, a Finnish photographer living in Prague, chose the latter approach for her diptych titled Split Up (2004). In one picture, she captures the image of a woman hugging her round belly as a mother’s confident act. In the other (or on the first, depending on how one views the diptych), you see the same woman sitting on the ground with a desperate expression and without a stomach. The photos acknowledge their arranged quality, but they are nevertheless psychologically credible thanks to the way they situate motherhood within an emotional "mine field" somewhere between satisfaction and frustration, fulfilment and emptiness, contented self-embrace and harsh honesty. Jiří Surůvka opted for the parody approach in his already well known work, Otcovství (Fatherhood, 2003). His laminated, blue father with a Batman mask—done with classically expanded Surůvkovian proportions and features—illustrates the specificity of birth in the male version. The author presents himself in the role of a proud father-superman, able to give birth to children without effort or pain. In this display, the spectator can take in various miracle births, where the mother is completely replaced by the father—whether it be Athena, who sprung out of Zeus' head, or Dionysus, who was born of Zeus' thigh. Similarly to Greek mythology, we see here a magic trick substituted for the physiological facts of birth which speaks to male intellectual creativity rather than to the dark movements inside the female womb. The man-artist has birth fully under control. He brings his clone into the world, and therefore no one ever doubts his paternity. Similarly to Surůvka, Lenka Klodová also takes on motherhood with some exaggeration. But unlike him she has a systematic focus, and it would appear that she has not yet exhausted her arsenal of motifs associated with the topic. In the context of the exhibit “Tento měsíc menstruuji” (This Month I’m Menstruating, Art Factory Gallery, 2004) she avoided using the obligatory “pad” iconography, choosing instead to mount a symbolic campaign called Demonstrace (Demonstration, 2004). This work consisted of a procession of paper pregnant women waving posters with anti-menstruation slogans, such as “Say NO to menstruation” or “To life without menstruation.” They played out one biological reality associated with the female, in contrast to another, in a very non-traditional way. Here Kodová draws from imagery considered to be a source of stereotypical expression “on the female role.” But at the same time she gave this role an unexpected, self-deprecating and also intrinsically optimistic form. Her pictures of women can be labelled subversive despite the fact that they “ridicule” traditional female values. This “ridiculing” allows us to view the situation in a new way: from the comfortably distant stereotypical depiction of the female “race.” In her version, motherhood is enriched to include a playful dimension exploring the “grand mystery” with some detachment. Klodová revisited the theme of pregnancy in the photograph series called Vítězky (Heroines), presented in 2005 as part of the Artwall project. She set up Vítězky as a visual analogy between pregnancy and athletic activity, i.e. a sort of “homage to mothers.” Of course, one can imagine other interpretations; the disarming impression that this bulging belly gives us relates to the widely accepted expectation that a pregnant athlete puts her unborn child at risk. In this regard, the winners demonstrate the paradoxes of pregnancy understood as both a virtuous discipline worthy of medals, and as a handicap. Via these bodies, starkly contrasted with the traditional image of passive, aestheticized pregnancy, the artist points out the limitations of the social model in which pregnancy is accepted as normal. Two years later, in the same place, another project devoted to motherhood appeared: a project called Otázky (Questions) by Silvie Vondřejcová. She used a public questionnaire to explore viewers' preferences concerning their real and hypothetical children. “If you had the choice, would you be bothered less if your child were considered by their peers to be a) stupid, b) ugly?” Vondřejcová asks in one of her seven questions, which are not—despite their seeming simplicity—easy to answer. They all ultimately relate to our often unpredictable expectations and our competitive value systems. Vondřejcová’s project speaks of pregnancy’s psychological dimensions. She expresses pregnancy, and the children who are born of it, as the fruit of our hopes, ideas and fears. Otázky was not Vondřejcová’s first work about the pregnancy experience. In 2005, she had the idea to gain weight alongside her pregnant sister. During this project she put on almost 25kg, but still she only gained half the amount that her sister did. In a letter on the project addressed to her sister, she explains that she’s scared of how her body is changing but is still, at the same time, determined to “go against convention and staid ideas of beauty to control her will and her body.”4 Her attempt held in itself a radical reassessment of the imperative “perfect” image while at the same time expressed a mental and physical solidarity with her sister. This tie surprisingly surfaced a year later. It was exactly a year after she began to programmatically gain weight with her sister that Silvie Vondřejcová found out that she herself was pregnant. Thus began the second, unplanned phase of the project titled Hmotnost (Mass). During her own pregnancy, the artist once again began to record her increasing weight and used the gathered data to revisit her previous experiment. The result was several noteworthy parallels between sisters. They got pregnant one year apart. During her pregnancy, the artist gained a lot more than she did during her weight gain experiment. Vondřejcová’s daughter was born a year (less than three days) later than her sister’s child. Vondřejcová’s experiment suggests another theme that still remains taboo today: sex during pregnancy. Lenka Klodová touched upon this issue in her dissertation work, a pornographic magazine for women called Ženin 1/05. One of the objectives set in the magazine’s pages was to resurrect the relationship between sex and childbirth: “I think this concept, which is a nightmare for a pornographically-educated man, can be a source of arousal in women’s pornography. The knowledge that I have inside myself a live, moving child and that during sex my husband is also there moving inside me allows for the integration of my whole family in my own body. This can be very erotic and arousing for a woman. I think a man is capable of the same, making love to his whole family."5 Lenka Klodová’s approach replaces the "empowerment" motif, which is so often common in pornographic productions, with that of "integration into the female body." This idea not only challenges the viewer to reassess pornography’s traditional logic, which stems from the binary relationship (dominator/dominated), but also illuminates a path to change in our understanding of the subject in general. The double singleness of the maternal body after all overcomes "material individualism, which is deceitfully ‘natural’ in the apparent conformity of the body,"6 and family rhetoric again refers to a self-assured female sexuality: one where pregnancy is not a prison, nor fulfilment of a woman’s biological role, but rather a source of physical and psychological satisfaction. Contrary to the majority of topics in the Ženin magazine, where a combination of text and photographs dominate the pages, Klodová depicted sex during pregnancy with the aid of analytical sketches of a copulating couple reminiscent of pictures in a medical or sexuological manual. She chose this approach in part for practical reasons—she herself was occasionally the female model for these sketches—but she could hardly get pregnant fast enough to reprise her role. Futhermore, this format allowed her to better capture the image of the whole family and underscore the presence of the child inside her place of “integration.” The fetus plays the main role also in Ondřej Brody's video entitled Dominik (2007). While Klodová focuses her attention on a female public, Brody’s work represents the male heterosexual fantasy of having sex with his pregnant patient in a gynecological clinic. However, Brody incorporates into this basic scene a real ultrasound exam done by an actual gynecologist. In comparison with typical pornographic production, the result comes off as rather subversive. Too much time is devoted to the interaction between the mother and the gynecologist and the actual examination, while the detailed shots of the sexual act take on a secondary role. Contrary to classical porn, here the male’s ecstasy is represented as something of secondary importance (nature). Most of the time he appears sweaty, and at moments also awkward. This is underscored by the apparent disinterest on the part of the mother, who is concerned primarily with the welfare of her child and mostly ignores her partner. Yet the manner in which Brody constructs his pregnant subject remains in the realm of strict patriarchal codes. The protagonist is not, after all, a nymphomaniac from a porno magazine or a video, but her role is indisputably characterized by her dependence on men. She is situated with them as a patient, sexual object and mother-nurturer. In this sense, the “dad’s” reaction to the fact that the child is a boy is typical. “You must be appy as a clam,” he claims spontaneously, evoking the traditional opinion that a mother’s value comes from her ability to conceive and birth a son. In this regard, the mother is subordinate to the phallic logic not once but twice: she accepts her lover’s penis and at the same time she identifies with the role of the privileged “owner” of a male heir. Like Lenka Klodová, Ondřej Brody is interested in the sexual aspects of pregnancy. But contrary to her, he does not focus on stimulation from an erotic experience (not even for the male). Pregnancy and sexuality are in his interpretation rather discursive tools with whose help he can analyze various photographic regimes bordering on pornography. Also central to his work is the viewer’s reaction to these taboo topics. His “repulsion” stems from prejudices that place sex during pregnancy into the category of perverse acts, or of imagined dangers. Here it is worth quoting a contributor to a certain internet discussion, according to whom men face a real danger during sex with a pregnant woman: the child could bite them.7 So now I’ve come full circle to my original question embodied in Lenka Klodová’s performances: “Are you afraid of motherhood?” As can be seen from the examples above, Klodová is not alone in her fascination with the unsatisfying aspects of pregnancy. If motherhood is a “catastrophe of the identity,”8 the aforementioned artists are looking for various ways to replace this collapsed concept with a number of variable identities built by unifying contradictory concepts: “me and them,” “internal and external,” “public and private,” and “physical and spiritual.” In this way, they create a grid within which the maternal project can take place. Footnotes 1 Carol Stabile, "Photographing Mothers," quoted in Rosemary Betterton's "Intimate Distance," xxx, pg. 127. 2 Sandra Matthews, Laura Wexler. "Pregnant Pictures." Routledge 2000. pg.1. 3 Nadja Roverová, Eugen Kukla, "Umění porodit" (The Art of Birth, catalogue), Prague 2007. 4 S. Vondřejcová, Documents on the Mass (Hmotnost) Project, 2005. 5 L. Klodová, "Zásady pro vytvoření pornografického časopisu pro ženy" (Basic Priniciples for Creating a Pornographic Magazine for Women), Dissertation Work – (VŠUP), 2005. 6 Quote in Note 2, pg. 14. 7 zdravi.idnes.cz/sexualita.asp?r=sexualita&c=A031208_150805_sexualita_jkl, found on 7.2. 2008. Eva Hauserová mentions this link in her article "About Sex in the Blessed State" (O sexu v požehnaném stavu), Rozrazil 02/2006, p.67-68. 8 Julia Kristeva, "The Language of Love." Prague, One Woman Press 2004, pg. 200.

01.01.2008

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment