| Umělec magazine 2010/1 >> Yunsheng’s Language of Love | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Yunsheng’s Language of LoveUmělec magazine 2010/101.01.2010 Ivan Mečl | grayscale | en cs de |

|||||||||||||

|

Zhao Yunsheng is the exact opposite of the typical image of the contemporary Chinese artist. He is hardly a scrawny figure with a ponytail, glasses and a goatee, an ironic look, and a casual blazer. Yunsheng has the figure of a bull, the disposition of a panda, and a round head with a buzz-cut. He is constantly drawing and painting in his apartment in a prefab housing estate on the outskirts of Beijing, not far from the main street (a main arterial leading out of town) filled with cheap restaurants and establishments offering erotic services.

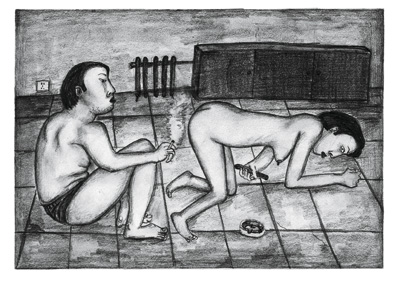

Yunsheng had just completed a series of four hundred pencil drawings when Shu Yang and I visited him at the end of the tropical summer in 2009. He had been working on them since 2008; at the outset, they had been a form of therapy for overcoming the breakup of a ten-year relationship. Later, however, other motifs made their way into the images: fabrications, erotic fantasies, more or less believable fables, and stories told by friends. Yunsheng counts on the viewer being knowledgeable. Chinese audiences understand certain allegories and symbols, but they too require the artist’s storytelling in order to be able to find a painting’s entire story. Like the rape of the daughters of Leucippus or Lot’s wife – all we need is a title or an elementary observation from the canon of representation and the entire adventure, including historical background, is revealed to us. Those whom curiosity has abandoned, however, will learn little about the stories hidden in the works of contemporary artists. They will be satisfied with the aesthetic experience and come up with an interpretation on the basis of a few universal symbols. We know that this is superficial, that it does not work, and yet a large part of contemporary art theory is based on this approach. We couldn´t care less whether an interpretation is correct or not, we are just happy to have any interpretation at all – an aesthetic text created as a fiction of theory. The drawing This Deaf Girl, for instance, comes from Yunsheng’s personal experience. Lying on the floor by a hole in the wall, we see his wedding photo, although in the end there was no wedding. Sitting on the floor is a man, and a woman is crawling over the broken photograph and into the hole in the wall. Their eyes do not meet, each is elsewhere in their thoughts. Appearing in the room are enlarged depictions of its residents and images from their thoughts. In Yunsheng’s drawings, the thoughts of the person depicted are often floating about in the action or they directly intervene in the events depicted. Events inside a house often make their way outside or onto the threshold of a space that remains closed and invisible to the passer-by. This is the case in Little Beijing House, where an unusual sex act with a young girl from the south takes place on the street. Like many other drawings, it was inspired by stories told by friends and conversations with the rural girls who sell themselves to urbanites in his district. They are naïve and lost girls who have left their mountains and villages to find work. On state holidays, they offer large discounts on their services. Perhaps they even do what is expected of offspring in Chinese culture, sending a part of their earnings home to their parents. Yunsheng does not judge in his drawings, nor does he moralize; only their titles (which I had to coerce out of him) touch on the character of their protagonists, often through the use of a sarcastic but understanding metaphor. This tolerance is apt, since he has to forgive himself for his many erotic fantasies. In the drawing She Finally Got Down to It, for instance, he depicts a piece of furniture designed to fulfill unusual passions and back-bending sex games. Some of Yunsheng’s drawings are a brief look at someone else’s unequal relationship of which he was an involuntary witness. Rat’s Treasure is about the owner of a tearoom and her jealous suitor, who followed her around constantly until that was all he did. Once, when Yunsheng stopped in for tea, she gave him a gift of an object in the shape of a Chinese gold ingot used for pouring the first pot of tea and the remaining tea during a tea ceremony. With time, all such objects take on this color and can become a kind of talisman – a symbol that we understand only if we have ever been in a similar situation. The drawing’s title is probably intended to confuse things even more. Some of the drawings can be understood as pure social satire. In He’s Silent..., Yunsheng appears in the role of an artist at a crossroads: death or loss of ideals. The allegorical death of the Chinese artist may be caused by a lack of means, for instance because he does not have the state’s approval to engage in artistic practice. Or the loss of dreams and ideals, a tendency towards pragmatism, which Yunsheng equates with castration. Zhao Yunsheng is currently preparing to publish all his drawings in book form.

01.01.2010

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment