| Umělec 2000/3 >> Paraphotographer or Photografist? | Просмотр всех номеров | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Paraphotographer or Photografist?Umělec 2000/301.03.2000 Jana Tichá | artist | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

Paraphotographer or Photografist?

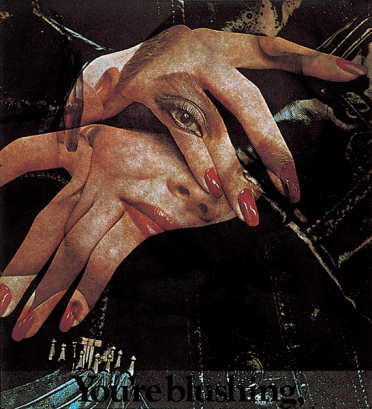

I did not make up the words in the title myself: the first one was invented by Robert Heinecken, when he tried to label his own artistic activities, and the other one was invented for Heinecken’s art by the art critic Arthur C. Danto. Both basically wanted to make clear that Heinecken is not a photographer in the regular sense of the word, meaning someone who just snaps the photographs, but that he is an artist who works with photographs. Moreover, he works with photography in its material form, and, as if with a finished object, he considers it to be a ready-made. He almost never uses shots he himself has taken; he uses pictures, which were created by others, and puts them into a new context. He does it in order to study the character of a photograph, its meaning in the sense of importance and it’s ability to convey value, and through this he has helped to increase understanding of our civilization and culture. Robert Heinecken (born 1931) is ”probably the most important artist you have ever heard of in your life,” said the Daily Herald after the opening of Heinecken’s retrospective in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago in autumn of last year. The witty exaggeration is closer to the truth than is usually the case for a bon mot. After the successful opening, the exhibition traveled to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and so most of the pieces returned, at least for a short time, to the city of their creation. Robert Heinecken spent most of his life in Southern California, after service in the Air Force, he studied art at UCLA (1960), and he stayed at the university as an assistant. In 1962, he initiated the formation of the Photography studying field in the Department of Fine Arts, and for the next 29 years he was the head of this field. In 1996 he moved to Chicago, where his first retrospective exhibition was organized in 1999—his first independent exhibition in 19 years. The exhibition, showing about 150 works, introduced for the first time a summary of his work. He had been an initiator of conceptual photographic work and of critiques of the media since the 60s and had created an interesting set of work, even though he had divided his time between fulfilling his obligations as a university professor and his own work. It’s not like Heinecken was completely unknown till last year: early works from the 60s, especially his three dimensional ”photosculptures,” photographs glued onto a three-dimensional artifact, were included in important exhibitions. Although his experimental work was presented in a photographic context, which was still searching in the 70s for something in common with art, it was obvious that he was pushing the boundaries of what was called photography somewhere else. The most important of these shows were the Photography into Sculpture in the Museum of Modern Art in New Your, in 1970, and the Photography in America in the Whitney Museum of American Art, in 1974. Already these early works studied the way images spread by the media manipulate us, how we have a tendency to form on this basis certain visual paradigms—a model for the way our life should look for it to be ”right” or ”beautiful.” This does not only concern our body or the things we use and consume; visual impulses from the media even produce models for our behavior, thinking and feeling. They form our opinions and dictate our emotional reactions. In the 60s and 70s Heinecken used, for instance, photography reproduced in magazines. That is how works like Recto/Verso (photograms from the pages of fashion magazines), or Costume for Feb 68 (a slide of an act with a collage background, combining planes of ”beautiful” detail with a scene most likely from the Vietnam War) were produced. We realize that at the boarder between the private and the public there is a place where we are being confronted by images from the outside, and by their manipulation; here the never-ending battle of analytical thinking and the seduction of images takes place. It is not necessary to constantly take it so seriously: the relief collage cycle of the Indian god Shiva will mostly make us laugh, and then we can start to think about it. The funny, bizarre interpretations of the god, whose agenda is destruction and regeneration, are put together by different pictures of products. This brings together a kind of assumed consumer identity of these products. However, Heinecken can also be very intellectual, when the topic demands it. Two portraits of the critic Susan Sontag, the author of the book On Photography represented the S. S. Copyright Project ”On Photography” (1978). Both portraits are put together as an assemblage of black and white snapshot photographs. One of the portraits is made from randomly found shots of the artist’s studio, his friends etc. The second is made from photographs of the pages of On Photography, which, thanks to different exposures, have different shades. It shows that a ”text” portrait is less readable and more deforming than a visual one. By the way, the somewhat awkward title of the work has its origin in a lawsuit, which followed the work’s display in the Museum of Modern Art in 1978, where Sontag wanted to enforce her authorship rights on her text. Part of the agreement was that Heinecken would give the source of the pictures, that is, the given essay including the copyright, which got into the title of the work. Heinecken, in the extensive series from the 80s Waking Up News in America, dealt with the function and meaning of a photographic image in television news. One part of this series is a quasi study of looking for the ideal host, whom Heinecken seeks among the contemporary hosts at the TV station CBS. He double exposes their faces and presents us with bizarre beings, which, thanks to the ethnic richness of America, are really very well mixed. Inaugural Excerpt Videograms from 1981 preceded this series. These were images taken directly from the screen, and were slightly visually altered (videograms are created by placing the photographic paper on the screen and are exposed by the light coming directly from the set.) In the 90s Heinecken concentrated on the phenomenon of commercial computers. He created a series of life-size two-dimensional figures, similar to those used in film advertising, and in them he comically matches up personalities, whose meeting is almost like something from Spielberg: the former first lady Barbara Bush finds herself in the presence of two men from an alcohol advertisement, or the old Hollywood legend John Wayne is placed next to Princess Diana. The works of Robert Heinecken are visually diverse; a clearly identifiable style cannot be detected in them. It is basically a disadvantage: in the art scene, not to mention the trade, artists without a ”trademark” have a harder time asserting themselves. Heinecken certainly could not do what Barbara Kruger does. She is now producing cups and T-shirts with her provocative political slogans. There’s no other way to explain why at her exhibition at Los Angeles MOCA these artifacts were displayed in a case in the exhibition space without a label saying, ”You can get these in the museum shop.” Furthermore, inside the museum shop, the same products were labeled with a price tag, with a sum that corresponded to the value of the souvenir, not to the value of the multiples of a famous artist. It is evident that art is infiltrating life as much as it can. So, all irony aside, why not? Do we know for sure where the line lies between a museum and a museum shop? This is also one of the questions Robert Heinecken indirectly asks. Robert Heinecken, Photographist: A Thirty-Five-Year Retrospective, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), 13. 2. – 24. 4. 2000

01.03.2000

Рекомендуемые статьи

|

|||||||||||||

Комментарии

Статья не была прокомментированаДобавить новый комментарий