| Zeitschrift Umělec 1998/3 >> For Pleasure, Against the Government | Übersicht aller Ausgaben | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

For Pleasure, Against the GovernmentZeitschrift Umělec 1998/301.03.1998 Vladan Šír | focus | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

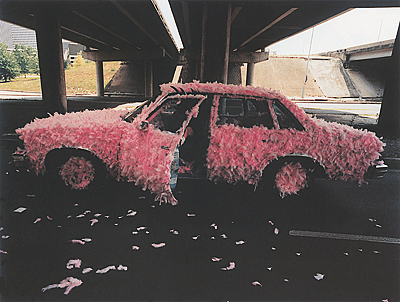

The end of March saw opening of the Art Car Museum in Houston, Texas. Originally an antique warehouse now looks like a Byzantine cathedral with domes and mosques. The roof shines with chrome and is decorated with car parts, components and a big red star.

Designed by well-known American car artist David Best, the Museum immediately suggests that what the visitor finds inside is no Picasso or a Young British Artist. Otherwise it works just like a normal art institution: it has its director, its permanent collection and it organizes exhibitions. The Museum opened with a presentation of its collection of eight art cars, photographs and a video by Andy Mann. The Museum’s selection criteria are “just normal art criteria,“ director James Harithas told the Artist. He considers a car to be an art car, “if it works, if it has something to say, if it is smart and well put together“. Art car, however, is a very broad term, which includes any intervention to a produced vehicle. If the author exchanges a few original parts for something that was not made for the specific model is just as artistic as transforming an automobile into a pile of metal which looks nothing like the original. Since Duchamp’s times one may consider anything as art so why not cars. Still, there is something Harithas is specially interested in: “I’m interested in anything with a political motif. So if it is a political car, of course I’m interested.“ Art cars are nothing new, they have always existed even though nobody called them that way. For decades they could have been found in Mexico, in Cuba or Pakistan where one could see perhaps most of various color modifications and car paintings. In the Caribbean, the main motif appears to be religious images while in the U.S. of the 60‘s hippie cars started to pop up expressing the owner’s political opinion publicly. Individuals take cars to express their political and esthetic opinions or just their interest. Interventions into an exterior or interior of automobiles have become a movement - not necessarily with artistic intentions - in the past 15 years. It all started when curator Ann Harithas commissioned several artists to make art cars for the Collision exhibition in 1983. The show then grew into an annual art car parade in Houston. With originally 60 cars, the parade now presents works by almost 400 artists and non-artists. Although there is a condition that an art car has to run, it is sometimes hard to believe they actually do. Next to such innocent alterations as a car covered with grass or dolls, pictures, mirrors, buttons and other trinkets, some of the April parades in Houston saw vehicles that remind more of a car cemetery or a small bomber. Recently, viewers have witnessed a burning car called the Waco Car for the first and last time. It was made in response to burning David Koresh, the head of the well-known religious sect, along with his followers by the FBI in his own ranch. The city hall then forbid burning cars in future art car parades. The art car phenomenon has attracted a large number of followers and fans all over the States. Visitors to art museums often feel uneasy and are afraid to approach so-called high art. In a museum with art cars, they have completely opposite experience. Often they spend two or three hours in a 4.000 square feet space. Considering the number of cars shown and one video, approximately 200 visitors daily is quite an impressive result. And it is not just because they are allowed to sit in the cars. “I was a director in five museums,“ says Harithas, “but I see a great difference in how people respond to cars, how they relate to them. It is one way you may perceive art at that level. We have no culture in Texas so in a sense this is a new art form.“ Cars not only break the barrier between art and museum visitors, anybody can make one. The Art Car Museums curators including a mechanic-curator sometimes wonder that people who have never been into an art museum and have never been interested in arts come up with references to modern art. Harithas has been trying to do this during his career. When heading a museum in New York State he trained prisoners for work as curators. “My sympathy was always with the artists and public who go to museums,“ says Harithas who has been a painter for twelve years himself. He is interested in how aesthetics works when art history is put aside. Making art cars is a new experience to artists themselves, a different experience they have with their “traditional“ work. “To me, it’s a great opportunity to go beyond the classical art world,“ says artist Larry Fuente in an interview for the Museum’s catalogue. “You’re outside the boundaries of the museum, you don’t have to ask anyone’s permission, you don’t have to get a show, you can take your art directly to the people. And as long as you’re within the law, or you can stretch the law, you can make any statement you want to the public.“ Other artist then started to make their art cars too as they all shared their freedom of not being part the art system. Car is immediately visible, responses to work are instant and more people have a chance to see it. Fuente also likes that a car is “a perfectly mundane object“ that anybody can afford - at least in the car-obsessed United States. With mass access to automobiles in industrially advanced countries, art cars take on another dimension in addition to the chance to express one’s ideas. This dimension is typical for today’s interwoven world. Once a symbol of life style and position of its own, a car is losing its symbolic meaning and its former variety. It doesn’t matter whether you have a new Škoda or Mazda in your garage, as cars look more and more alike. Their operation also becomes more demanding: as a result of political fights gas prices increase, car owners have to pay mandatory insurance and then they spend hours in traffic jams. The magic is gone. With their art cars, people express their opposition to continuous unification of the world, corporate domination and they try to bring power back to the individual. It is symptomatic that the movement’s center is in Texas that is known for its citizen’s independence and reluctance to give in to federal institutions yet a seat to many large and influential corporations. As media discovered art car movement and started reporting on art cars, artists started to worry that it could grow into an institution and become just the opposite of what it now stands for, particularly now that art cars have their own museum. Representatives of large art museums, however, look down on Art Car Museum, according to Harithas, or at least he hopes so. He is actually more worried that the art car parade and the museum draw attention of corporations. “Like anything in America, you have to be careful that the corporations don’t take it over,“ he says. His Museum is financed through grants and private funding. In any case, interest in art cars keeps on growing all over the US. Art car parades similar to the one in Houston are now being organized in other states of the union and are planned in Korea and Japan. “It looks like the movement is going to grow,“ says Harithas. “People come look at art cars and then they go and make one of their own. Everybody wants to have an art car today.“

01.03.1998

Empfohlene Artikel

|

|||||||||||||

Kommentar

Der Artikel ist bisher nicht kommentiert wordenNeuen Kommentar einfügen