| Umělec magazine 2007/2 >> Daniela Baráčková | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Daniela BaráčkováUmělec magazine 2007/201.02.2007 Jiří Ptáček | new faces | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

At the end of last year Daniela Baráčková fell prey to the cultural gutter press when her former teacher, Jiří David, pointed out similarities between her video and another project, entitled Replaced, by Barbora Klímová. Baráčková’s work is a record of a busy New York street on which Baráčková is seen stretching out her arms—just like the artist Jiří Kovanda three decades earlier in Prague. This was alleged to be quite similar to the remake of five performances for which Klímová received the Jindřich Chalupecký prize. For David, this was sufficient evidence to say Klímová’s work is derived from it. Though it eventually came out that the accusation was unfounded, the case brought unintended fame to Baráčková. This was unfortunate this artist has produced a lot of other works of far greater merit.

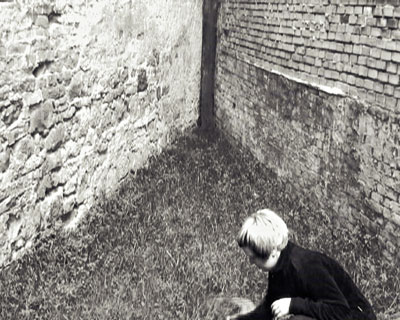

When Baráčková (born in Boskovice in 1981) came to the Czech Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design (VŠUP) in Prague, she was interested in locating texts in public places. On the outer walls of houses at the outskirts of the city she would write sentences familiar to us from childhood—sentences we once considered wise and true, but in many cases we discover, later, that they are just folk-sayings. (“That’s The Way The Ball Bounces,” “Life Goes On,” etc.). For a change, she inscribed simple phrases about the philosophy of a hunter onto animal hides. In this way, she has cultivated her sense of irony, and then she shifted to video. In the recordings Carrefour (2005), or Pamětní deska (Memorial Placard, 2005), she used a hidden camera to reveal situations when people appear stupid and bourgeois, or when they might be. In both works she found a wealth of “evidence” that was perhaps all too popular with the public. Baráčková’s staged videos are short. Concentrating upon very simple actions, the artist herself always plays the main role, as in Vzpomínáme (I Remember 2005), where the artist imitates piano fingering on a wall under a commemorative placard. In Srp (Sickle, 2005) she cuts grass, for a long time, in a corner between two walls; the chaotic picture presented in the video Gumák (A Wellington, 2005), copies her jumping over a creek wearing one Wellington boot. The static video Tramp (2005) is based on the narration of a bizarre erotic childhood story on a camping trip. In these videos, Baráčková exchanged irony for a dark, chilling, but still situational kind of humor. Baráčková has apparently realized that she does not have to seek out absurd situations, but that they are always present, there in front of us in the seemingly banal reality of the everyday. If they have any purpose or goal, she does not need to know. Tramp is an exception—because as a man enters into the children's camp late at night and gently strokes the body of a naked girl with a leather glove—the video is presented as a strange message to eternity. There might be some signal or a key out there, somewhere, that could help us to understand these films more. The camera carries a peculiar magic: it can change our ability to experience things around us, and to “do something for her.” But why aren't Baráčková’s videos on Youtube, like thousands of others? Maybe, despite all their inherent humor, they also bare witness to something more profound. The medium of never-ending, looped virtual entertainment would debase them would deprive them of the opportunity to bring their macabre game across, not as a pathological sign; the mundane rendered as something other than as a triviality. Maybe it is that she exposes a longing to get to know a little bit of ourselves and something of what we “say about each other.” Promising in this aspect is the video Pavel a panelák (Paul and the Tower Block, 2006). It fits into the observational line pursued by Carrefour and Pamětní deska. But the boy in sweats swinging while listening to the radio needs none of Baráčková’s usual irony. She is as attentive to him as she is to the wind bending the poplars outside, and the shiny enamel of a late-Communist apartment building. She seems to me an interesting new video artist. And recently she started painting.

01.02.2007

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment