| Umělec magazine 2008/2 >> Engraved Snapshot: Jitka Mikulicova | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Engraved Snapshot: Jitka MikulicovaUmělec magazine 2008/201.02.2008 William Hollister | new face | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

It’s a deceptively simple game; it’s child’s play. Rip a piece of paper into shreds of various shapes and sizes, let them fall, scattering like snowflakes upon a table, and then push them around, arranging them variously until images emerge. That which comes together this way—order from chaos—says different things about one’s inner landscape than an image deliberately drawn.

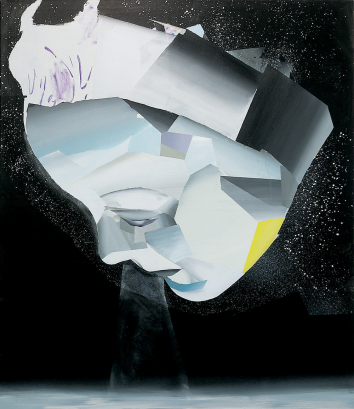

Figuratively speaking, it is in this way that Jitka Mikulicová (b. Hustopeče, 1980) introduces the spectator to her ideas. Working with various media, she has been developing an internal language, an iconography of fragments. It’s a language that combines this paper-play with a rigorous intellectual process of preparation—one that invokes art history and critical methodologies that make the art of the Central European emerging generation so remarkable. Exhibiting since 2003 and living in Prague, Jitka has studied in Brno under the tutelage of Martin Mainer, in Leipzig with Neo Rauch and in Prague, Jiří David--graduating from the Czech Academy of Fine Arts in 2007. Scraps of paper are shards of the past memories, the present—of ideas, of dreams, of the future, the sacred and the profane—of death. They both define ideas and eclipse them. From these forms, on close examination, materials are revealed not to be of scattered paper forms, but carefully crafted shapes emulating torn paper. In some works where panel background is not wood, but wallpaper stickers. “I was surrounded by woodwork objects that my father made. I came across the scraps and fragments of wood; I substituted these with cheap wall paper,” explains the artist. “From strips of wallpaper, I made pictures whose contents evoked the aesthetic of folk art.” Indeed, Jitka worked from this basis, but substituted such hardwood—sacred elements—with the mundane formats of wallpaper and other fake wood panel paper to form initially abstract landscape. From a distance one imagines the authentic format of handcraftsmanship, but close up, one identifies instead the cheapness of available forms the present state of things—but when set on canvas, they are recuperated with a nobility that dignifies the present moment that dignifies the world of this artist in her surroundings. As she says in her own portfolio statement, these are “converse shapes, assembled into a pile of wooden garbage with no use, became fascinating and inspiring—thanks to this experience I started dealing with fragmentation and composition of nonsense shapes.” An initial tendency towards abstraction found its way into portraiture, with an evolving fragmented background pressing ever forward. One of three large canvas portraits presented recently at Prague’s Jeleni gallery Next to the Wall (2008) is a portrait of the artist’s mother whose clothing and magazine-model pose indicate an attitude from years gone by, now faded. Here, the scrap-paper forms of abstraction are jarring linear sfumato textures that form a field stone wall and are work into tree structures in bold quick brushstroke upon a yellow background. It is in the partial juxtaposition almost of the artist herself into the poise of an individual in the not-so-distant—but very different—Central European past, that one imagines a young artist delving into a deliberate ambiguity of intention, locating herself in the present, but frozen in the past. For the artist, the apparent “socialist typology” is not the stated issue; rather, here is an old photograph, a relative in black-and-white. When transformed on canvas, the rough edges of the wall, the raw brush-strokes of the wall combine with intense color in an atmosphere of enhanced tension and mystery. Two other large portraits in the Jeleni exhibition are similarly revealing of this progression from abstraction. In Portrait (2005) the gaze of a woman is fixed downwards; perhaps a socialist realist statue, the sculptured face is upon a dark acrylic surface looking down indifferently upon the horizon of humanity. It’s a hybrid spirit of religious icons carrying the blank gaze of the Czech era of post-68 Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia. Representing much of the culture that preceded the artist, it is an identity with no fixed label; but we assume it is a deity, and we know it is female. Not insignificant is that this white face with a blank expression is presented starkly against a black starry background—again those small white paper scraps. Whereas in its case, that field is the sky, in the painting in the adjoining Jeleni room, Mirecek (2008), the dark background is more of an abyss. This spirit-faced boy glows hauntingly with a fixed gaze forward, eyes wide open in a calculatedly rough-and-ready folk stylized manner. It is the face of a young boy on a tomb, whose existence captured the imagination of this artist. However haunting, there is no immediate hint that the image is the face engraved on a grave stone. Mireček was born the same year as Jitka, and lived in the same town—and on the tomb, has in stone the same name as the artist herself: Mikulica. “The painting came about as a recollection of my particular relationship—a feeling to the boy whom I knew only through that gravestone, whom I never met.” By modifying to canvas the stone-etched image, Jitka transformed the processes behind the work. The folk style of the original was maintained, even with slightly crossed eyes. The artist has found a parallel observing the photograph engraved for the dead, to explore when resonance there might be between her life, now, and that of her surroundings. This painterly exploration of the stone form led Jitka one step further—to a cycle of grave stones. These are not on canvas, but actual basalt stones—stones of the sort that serve as grave markers, with images of the deceased etched into their polished surface. But the people depicted Jitka’s series are not dead; they are caught, frozen in the middle of life, enthusiastically smiling as from snapshot portraits—like that spiritual Portrait, socialist realist perhaps, but in any case frozen in an idyllic, optimistic state. Jitka even had herself portrayed upon one of these, with her shirt buttoned tightly at the top, smiling optimistically. What better future can one look forward to, if not one engraved in rock. “I worked with momentary feeling,” she explains of works that offer a multiplicity of layered interpretation. “The stone portraits are captured (idealized) moments whose smiles, delighted glimmer in their eyes are frozen rigidly in optimism.” Jitka works mostly at her Karlin Studio atelier where from a school desk pulpit and white iMac computer, she is surrounded by the elements that are spun together to make her work. Children’s collages from a school are on one wall, among photocopies of Edouard Manet’s Jardin sur l’herbe along with the stencil graphics of Jaroslav Roessler, Josef Čapek, S.K. Neumann. Herbert Bayer’s 1932 Lonely Metropolitan of open hands with collage eyes in front of a tenement house, is posted near a photograph of a palm open, within which is a square photograph of a relative whose face is partially obliterated by a white square—a preparation for a future painting. Nearby is another small black-and-white photograph that has been transformed into a painting. Jitka’s scholarly approach shows up strongest in the large acrylic canvas, Stairs (2007). The painting is based on one posted photograph—an old black-and -white portrait of a relative standing vertical against the horizontal stairs evocative of Eisenstein’s Potemkin. Jitka’s painted portrait of a female relative from that past-life socialist world, works into the shadows the cold basalt forms of Mireček. And, as with other portraits, the face is partially eclipsed by a white square—a paper scrap; and the leggy ladies in the distance have been obliterated, replaced by the lower torso of a single “It girl” in the background walking downwards. Here, history is recreated, slightly set aside, slightly distorted, yet faithfully re-created. In this evolution from abstraction, Jitka has shown that the possibility to render the human form, individual, anonymous or even as a sculptural nude—a systematic study of recuperated art genres—can be a complex rendering of interplaying surfaces, ideas and generations—a game seemingly as simple as child’s play.

01.02.2008

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment