| Umělec magazine 2005/3 >> From Blank Spot to Exotic Marginalia | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

From Blank Spot to Exotic MarginaliaUmělec magazine 2005/301.03.2005 Natalia Filonenko | Ukraine | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

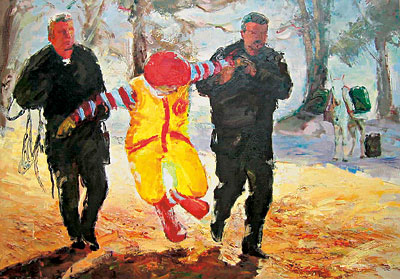

Culture Policy in Post-Revolution Ukradne

According to Boris Groys, art and policy operate in the same space today. We live in a society in which every major politician generates many more pictures and images than any artist. Even second-rate terrorists and politicians are much more effective than the most famous artists. Terrorists blow up a bomb, and the entire world’s media network along with it. Politicians have all the means to generate media images at their command. Fortunately, terrorism is not a Ukra-inian problem. As for the politicians, Grois’ words mean even more here than he could imagine. To realize the power of Ukrainian mass media in the post-revolution situation, one need only observe the way that new cultural policy is developing in strict accordance with the Ukrainian president’s personal liking. Each of his media messages is implicitly taken by official representatives of culture. Esthetic perception of one person is turning into a state culture program without any considerable efforts of this person (and often, unknown to him). This effectiveness of Ukrainian media can, first of all, be explained by the unbalanced period between two political eras, when all events and statements become significant. Second, interdependence of culture and policy in a country that only tries on a toga of democracy is most unconcealed. Art has always been the window-dressing and ornamentation of the political power; so, its development has always been determined by the acting power. It is characteristic of contemporary Ukrainian art too. It only was after perestroika that contemporary art was allowed to leave the underground and to act as an alternative to the Union of Artists during last twenty years. As early as during the president’s inauguration, the program for the development of a new Ukraine was prescribed: the ceremonial flag and mace of 17th century Ukrainian hetman Bogdan Khmelnitsky were brought for the ceremony; the president’s children were wearing Ukrainian national costumes. This Cossack and hetman demonstration transformed the inauguration into an official declaration of the cult of national culture. Practically, the media message offered society a way of conservative spirituality and cultural regression. After all, it looks strange after the revolution. Cultural renewal would have been more logical. Under Viktor Yushchenko, the cultural atmosphere has taken on new characteristics. These are traditional family values, religiousness, and patriarchal character. The new power has a tendency to rely on history. In the days of the revolution, Yushchenko mentioned “Ukrainian millenium tumuli” and Tripolie culture.1 The mayor of Kiev received an order to rebuild the Dessiatina Church, ruined by Tatar-Mongols, even though no historian knows what the church looked like. The city administration, already famous for its actions that deprived society of the right to have its own ruins, continues to falsify ruined monuments by substituting them with kitschy objects. New “historical” paintings appear dedicated to the history of Ukrainian Cossacks and monumental works that picture the events on Orange Square. The President himself visits these exhibitions from time to time. It is possible that this is sincere, but it looks like a Soviet state of affairs. A cultural monument is being planned dedicated to the victims of starvation in the Ukraine in 1933, and, beside that, to take one snowball tree from each of the villages that suffered from hunger and to plant them on a hill so that the entire forest grows there with berries as red as people’s blood. Abroad, Ukraine is exclusively represented by decorative art and folk dance groups. The pop singer Ruslana’s dances and songs also seem folk. The music group Greenjolly took part in the Eurovision song contest. Their song “Nas bagato, nas ne podolaty” (We are together, we are invincible) was heard in the streets during the revolution. However, even after numerous improvements, their video comes across as mediocre “orange” propaganda, a rhyming slogan for meetings. In Ukraine, the cultural scene has never been particularly civilized. All decisions have been taken in accordance with the personal preferences of ministers and officials. Culture is a sort of indicator of pluralism in society. Today, the country’s whole cultural solution gets more and more orange and glistens with bright colors of national embroidery. The time of “true values,” “people’s relics,” and the return to “national roots and our origins” has come. Ukraine is turning from a white spot on the global cultural map into exotic marginalia. Contemporary Ukrainian art is being squeezed into the limitations of a 19th century farm. It is not only that any critical or analytical approach characteristic of contemporary culture is unwelcome, which is natural for any power. Additionally, under the flag of spirituality it is declared seditious and abusive toward those “values” and “roots.” The Museum of Ukrainian Spirituality instead of a Contemporary Art Museum One would imagine that the choice for a European democratic way of development would have opened wide pro-spects for art, and its development would be refined taking western experience into account. Revolutionary changes have taken place in the eco-nomy and politics, but not in culture. Despite the oft proclaimed “striving for Europe,” there are continuing attempts to liquidate contemporary art. This practice itself is becoming a tradition. Officially, contemporary art is still absent. Instead, there is a post of the parliamentary adviser on culture and spirituality. Soon after his inauguration, the Ukrainian president announced the establishment of a “Ukrainian Her-mitage” as a museum of Ukrainian spirituality. What that means, however, isn’t entirely clear. This new museum is to be situated on the premises of the former Arsenal that had been intended to host a contemporary art museum in the Kuchma era. The Fund of Viktor Pinchuk had an agreement about a long lease to use part of the former Arsenal for a private museum. In the course of two years, this abandoned area was supposed to be transformed into an active institution. As part of the Fund’s program Ukrainian Contemporary Art Museum, two large exhibitions, First Collection and A Farewell to Arms took place in 2004. The importance of this undertaking cannot be overestimated; there is still no museum of contemporary art in the country. Contemporary art that appeared in the mid-80s is still not in the field of museum systematization. There are only several private collections. However, none of them represent all the leading artists and their works. Seemingly, it was so fortunate that someone finally came who was ready to invest big money in the project. However, the new power shows no delight in this regard. First, they reversed the agreement with the city administration about the premises. The Fund requested that the Ministry of Culture permit at least the big multimedia exhibition, Testing Reality in the Arsenal. Work on the exhibition began a year ago. The Fund invested considerable means. The whole concept and all the works selected for the exhibition were all related to this concrete area. However, the Ministry of Culture responded by refusing, following this with an ingenious motivation, “archaeological and speleological research and repair works in the Arsenal.” The Ministry representatives also discussed plans for antifungal treatment of the Arsenal’s walls and health issues for the visiting public. At the same time, work indeed took place there. However, those were works to prepare the area for the exhibition organized by V. Pinchuk’s Fund. The state has no means for the announced restoration work (even existing museums are in a catastrophic situation). In order to liquidate the uncertainty city mayor Alexander Omelchenko fenced in the Arsenal and put a lifting crane there. The decoration looked very convincing. The exhibition was urgently transferred to the building of the Ukrainian House. It suffered losses due to a shortage of space and time for the installation of all planned works. The presence of contemporary art museums in this or that country is significant evidence of the presence of some degree of democracy. The cessation of the activities at the art center in the Arsenal is a blow to the art, the artists, and spectators. Again for an uncertain period of time, there will be no opportunity to see or take part in big Ukrainian projects whose number is close to zero after the closure of the Soros Foundation Culture Program in Ukraine. However, today, a well-known principle in Ukraine is at play: ‘let my neighbor’s house burn down even if it harms my own interests.’ Despite these unfavorable conditions, the Testing Reality exhibition opened on May 21 featuring video, installations, photography, and paintings. The Viktor Pinchuk Fund continues to work on the Ukrainian part of the collection. This year, the international New Acquisitions exhibition at the Palazzo Papadopoli was represented at the Venice Biennale with Nicolas Bourriaud as curator. This project marks the beginning of the international part of the Museum collection. The Contest among Ukrainian Representatives at the 51st Venice Biennale. Just Another Profanation People’s awareness of the Venice Biennale is unfortunately not the result of successes but scandals related to the two previous Ukrainian presentations in Venice. The fate of the Ukrainian presentation was not determined by the experts on contemporary art but by the officials on a pseudo-cultural basis. The new Ministry of Culture headed by the new minister – pop singer Oksana Bilozir – made a decision concerning Ukraine’s participation in the 51st Venice Bien-nale arguing that, “after the Orange Revolution, we have no justification for ignoring this international event.” It is itself evidence of a complete misunderstanding of the meaning of international presentations on such a level. Having made no attempt to understand what all this was about, (none of them studied any catalog or exhibition of contemporary art), they ordered the Union of Artists to organize the contest. Andrei Chebykin from the same Union, president of the Art Academy, was appointed a commissar. The Curator, Viktor Sidorenko is the same who worked at the previous Biennale. An artist and academic, Sidorenko is also director of the Institute for Contemporary Art Studies belonging to the same Union. It goes without saying that at the 50th Biennale the Institute presented Viktor Sidorenko. The list of the grand jury, selected by unknown people was announced; it included only a few contemporary art experts. They issued a statement saying they consider the contest a farce, the majority of the commission members and the commissar himself incompetent, and the participation of artists in the jury impossible, and promptly resigned from the jury. However, the organizers did not take this into consideration and announced the contest of projects, listing neither conditions nor criteria. The projects thus were submitted by anyone who felt like it. The jury worked without any procedural norms. On March 11, they somehow chose two projects not related to each other: art glass by Andrei Bokotei, rector of the Lvov Art Academy, and the exhibition-action by the group of young artists Revolutionary and Experimental Space (R.E.S.). The protocol of the session contradicted common sense and cast doubts on the professionalism of the majority of jury members. The extracts from it sound like funny jokes notwithstanding the seriousness of this “report.” Unsatisfied with the jury’s decision, the Ministry of Culture and Art reversed it appealing to would-be public opinion. In response, the group RES together with the political organization Pora organized a press-conference in UNIAN2 on March 17, where the Ministry officials confessed that they were “not aware of the materials.” However, the second session took place the next day. The jury, which had been openly considered incompetent the day before, included Ministry officials. They were bold enough to publicly estimate the art value of separate projects and defectiveness of contemporary art as a whole. Besides, the commission included seven more members who bore no relation to contemporary art. As a result, the project by Nikolai Babak Your Children, Ukraine received a “clear” victory by a majority vote. Force majeur excuses everything and a noble aim excuses non-democratic means. Again the role of the Ministry was not in regulation but in editing. The regulations on the contest were created and backdated to legalize the presence of Ministry representatives on the jury. Now the deputy minister could act as the jury chairperson. This document entitled them to “recommend artistic improvement of projects” and proclaimed decisions of the jury invariable and definitive. The situation of the Venice presentation is only a particular case, but it demonstrates how questions are addressed in culture today. It isn’t that contemporary art is being ignored; there is a fundamental absence of any professional approach and there remains a deliberate unwillingness to create effective schemes of work in culture. The revolution spawned the hope that the new democratic and non-corruptive power would obey the law, prevent abuses, and provide “equal opportunities;” the officials would play not an expert but regulative role; the experts would make decisions. However, the profanation of the idea of an open contest again took place. The lobbying of the pre-determined winner was so strong that they finally ceased to wear a mask of democracy. All this not only compromises the new Ministry of Culture, but the new power in general including president Yushchenko whose pochvennichestvo soil philosophy3 and aversion to contemporary art is taken by many as an ideological excuse of such actions of the Ministry of Culture. Your Children, Ukraine Under this title, Nikolai Babak represented his melancholic assemblage of enlarged photos from family archives and rope dolls in national costumes. The artist collected the images in his native village, demonstrating his ancestors’ and neighbors’ way of life—Ukrainian peasants under Soviet rule. With a concept heavily defined as the “imperishable height of human existence in the bosom of Memory,” Babak asked the question, “What are we?” Who among us has never got really bored looking through somebody else’s family albums? The epigraph chosen by the author for his project, the words of Miloš Forman, “Do not shout about the whole world. Speak about your village but make the whole world listen to your words,” sound convincing if the medium of cinema is involved. Not even the pre-sence of a “media element” – the artist reads the history of his village from a monitor – can modernize such a project. Some members of the commission seemed to feel uneasy in this regard, as there was no apparent motivation. Indeed, the agenda for the first meeting even contained recommendations to include “contemporary elements” in the project. They did so at the last moment – the history of the village on a monitor was substituted with documentary materials about the Orange Revolution. The past is in one hall, the present in another. It goes without saying that the Minister of Culture opened the exhibition in a national costume. She spoke about an “exhausted” Ukraine. Any spectator capable of grasping a clear art expression would likely leave the exhibition in great perplexity or, at best, say something to the effect that, “It is a pity that the Ukraine, along with other underdeveloped countries of the world, is still unable to represent any real contemporary cultural product.” The opening of Pinchuk’s museum presentation attracted lots of visitors, but it was not honored with attention by a Minister. It is very sad that Ukrainian officials do believe that the Venice Biennale is a place for the presentation of state ideology and history. It is impossible to convince them that it is not necessary to talk about the past or present of the country in Venice. It is not necessary to turn souls inside out demonstrating all sacred things. The Venice Biennale is not the place where we should demonstrate to the world that we love independent Ukraine and respect our ancestors and traditions. It is natural and does not demand any proof. Deputy Minister of Culture Olga Bench declaimed, “Ukraine has its own conception of contemporary art. Art should bring harmony and spirituality.” And just like Nikita Khrushchev, she advised that contemporary artists should exhibit in gay clubs. In general, so many things in the country are reminiscent of the Khrushchev thaw of the 1960s – there are changes for the better along with many absurd and unprofessional things. Additionally, there is something from the 1920s, when fundamental decisions were made by commissars in leather jackets – our power today is people’s power too. Today’s “commissars of culture” (who wear natural furs today) are in charge of ideology as at that time; and nobody is concerned about their unawareness. It is not important. Instead, they know what spirituality is. Revolutionary and Experimental Space The initial choice of the recent group of young artists RES came as a surprise for many. There were projects of more known artists for the presentation in Venice. However, that first choice was more reasonable. Many young members of the group managed to show that they have contemporary art such that their delegation to the international forum could have been regarded as an investment in the future generation. It could have passed for compensation for the complete absence of any system of education in contemporary art. It is a pleasure to establish that twenty years after the first wave generated by perestroika the second wave was generated by the Orange Revolution. We know from our own experience that revolution can transform communication and bring people together. Due to the Orange Revolution, Kiev’s square, Maidan Nezalezhnosti and Kreshchatik Street have become special areas, where the word freedom, which artists used to consider personal property, became the common property of the people. Young artists went out of their studios onto the streets and squares. Despite the cold on top of all the rest, many nevertheless drew pictures on tarpaulin tents. They created paintings and posters and hung them on Kreshchatik. There, the group of young artists RES spontaneously appeared and included students and recent graduates of the National Art and Architecture Academy. They painted expressive works and exhibited them on Kreshchatik and opposite the Cabinet of Ministers. RES members began to work right on Maidan, but that was during the revolutionary days when Soros Contemporary Art Center (CAC) Director Yuri Onukh granted exhibition halls to them as experimental premises. They worked in open studios for three weeks after December 4, and then they organized an exhibition as a spontaneous reflection on the revolution. The works were periodically brought out onto the streets of Kiev, and CAC visitors could participate in a process expressing their civic position by means of contemporary art. Nobody could imagine then that after three months the same group would be protesting against the politics of the new Ministry. On March 28, they gathered together with the Pora organization on Bankovaya Street. The action, against corruption in the new Ministry, proclaimed and continues to mechanically repeat the mantra about transparency, openness, and participation of the public in decision making that does not work in practice. Equipped with posters and loud-speakers the group members conducted several performances opposite the presidential offices. One of group members portrayed petty intrigues; others wrapped themselves into transparent film and screamed “Non-transparent“ through loud-speakers. Unlike other protest groups this one was too loud. Just an hour later, a representative of the administration appeared; he took their documents and gave them a contact phone number. Nobody ever answered their calls and no official response was given to them. What are the prospects for this new generation? How many years of their lives will they have to spend to prove that contemporary art has the right to exist and to get rid of the obtrusive and baneful patronage of the Ministry and the Union of Artists? Orange Revolution is not Cultural Revolution In other countries, whose examples Ukraine wants to follow, the affection for national traditions is not incompatible with the development of contemporary art. In Ukraine, however, there is an apparent paradoxical confrontation of national values and contemporary culture, as if it were necessary to choose between them. The new power regards national exotica as the primary instrument of external PR, such as for tourist attractions. Indeed, at the end of April, the president signed a new order: the Ministry of Culture now turns into the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Obviously, as long as the post of president is there, the personal characteristics of the individual at that post will influence cultural officials. Kuchma’s era for contemporary art was characterized by indifference and non-intervention. His team was never concerned about any ideology other than the power of money. Unfortunately, this attitude seems healthier for culture today. Today, we are thrust into a spiritual fundamentalism, a sort of soil philosophy. However, as any fundamentalism that works for rebirth of “eternal” identities and values, this one has a present-day root: this particular phantom of the archaic has been defined by the present situation. This fundamentalist “return to traditions” is in fact a contemporary invention. The new representatives in power aspire to inculcate “moral values” into society, having forgotten that they had come to power due to the presence of these values in society. A society with such deeply rooted regressive and reactionary problems needs a revolution. Revolution is always a deed in Jacques Lacan’s explanation of this word. Deed is a gesture of breakup of symbolic ties and regrouping of the previous symbolic code. Ukrainian society performed a deed but did not complete it as they did not restructure a symbolic system. Liberation elements of culture were not concerned and Maidan cannot substitute for the development of culture. This is why Cultural Revolution is necessary as a continuation of the Orange Revolution and here, the battleground should shift from a public level to a personal one. The art community remains in a situation, which is even worse than under Kuchma. It is in its habitual opposition, which now opposes the official pseudo-archaic culture and orange pop culture. For the future, their intellectual task is to realize and proclaim their fundamentally different cultural identity.

01.03.2005

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

|

04.02.2020 10:17

Letošní 50. ročník Art Basel přilákal celkem 93 000 návštěvníků a sběratelů z 80 zemí světa. 290 prémiových galerií představilo umělecká díla od počátku 20. století až po současnost. Hlavní sektor přehlídky, tradičně v prvním patře výstavního prostoru, představil 232 předních galerií z celého světa nabízející umění nejvyšší kvality. Veletrh ukázal vzestupný trend prodeje prostřednictvím galerií jak soukromým sbírkám, tak i institucím. Kromě hlavního veletrhu stály za návštěvu i ty přidružené: Volta, Liste a Photo Basel, k tomu doprovodné programy a výstavy v místních institucích, které kvalitou daleko přesahují hranice města tj. Kunsthalle Basel, Kunstmuseum, Tinguely muzeum nebo Fondation Beyeler.

|

We Are Rising National Gallery For You! Go to Kyjov by Krásná Lípa no.37.

We Are Rising National Gallery For You! Go to Kyjov by Krásná Lípa no.37.

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment