| Revista Umělec 2004/4 >> A New Museum in Ceauşescu’s Palace | Lista de todas las ediciones | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

A New Museum in Ceauşescu’s PalaceRevista Umělec 2004/401.04.2004 Maria Rus Bojanová | commentary | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

The October inauguration of Bucharest’s National Museum of Contemporary Art (MNAC) may be the spark of vitality that will bring Romanian artistic society away from its transitional struggle. Situated in the east wing of Ceauşescu’s palace, the museum is huge. Although it occupies only 4% of the building which, with 400,000 m2, is the largest in the world, second only to the Pentagon, it spans across 16,000 m2.

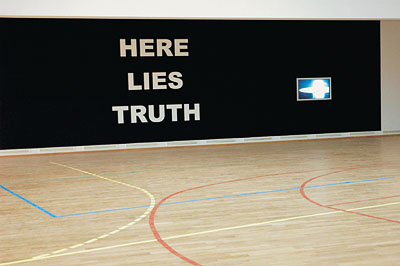

After the revolution in December 1989 that concluded Ceausescu’s dictatorship, and after public debate on the role and “necessity” of the House of the People—known worldwide for its megalomaniac proportions, it was decided that this building would host the two chambers of the Romanian parliament, an international conference center and some other state institutions. Until recently, the creation of a new contemporary art museum hadn’t been a top priority for anybody. But the pressure to finish converting the palace has led authorities to combine needs and to grant the remaining space—that is, the space that had been initially intended as private apartments for the Ceauşescu family—to a new cultural institution, even if the costs of the project called for a considerable financial contribution, the equivalent of half the country’s cultural budget. In any society, artistic spaces function as resonance chambers absorbing and redirecting shock waves to ensure a permanent exchange of ideas and opinions. It is not at all surprising that the decision to create the museum, taken with no prior consultation with the artistic community, brought about vivid debate. Many artists found the location chosen by the Government odious, and protests came along very soon in various forms. Even if the great majority of the artists understood that no other practical alternative for this museum could be found, multiple pressures were brought to bear to stop the work and to have the museum located elsewhere. The most radical faction in the Romanian art milieu considered this initiative an offense to the artists because, in only one gesture contemporary art has been brought right under the nose of power—the Parliament—perceived as an uncultured and obsolete institution. Perhaps as a reflex inherited from the communist period, the obsessive question among artists was, can one be independent while being so close to power? Under the dictatorship the effort of artists was so oppressed by communist paranoia that for many artists it was a living hell. The creation of this new museum has also determined a change concerning the distribution of influence in Romania’s artistic community, amplifying all the existing controversies to a maximum. The traditional artists—the most numerous—have criticized the large dimensions of the new museum as being far too grand for such an insignificant artistic movement such as that using new media. In reply, the visual artists considered “contemporary” blamed the traditionalists for lacking any vision, for what they call “postmodern postimpressionism.” To be stuck in the traditional mold, they argued, is nothing but the refusal of the traditionalists to acknowledge the truth, the progress undergone by art. As often happens in such situations, the personal moods and frustrations have predominated and the gap between the different factions widened. Few were neutral. In such a polarized artistic environment as in Romania, to keep and express an objective position takes courage. The most fashionable tend to oppose any initiative. Putting a new and open institution in the heart of the once forbidden Romanian citadel is no easy or acctable task. But, if the location of the museum was problematic for many artists, the same can be said for the politicians: few agreed to the installation of such a “dangerous” institution. Debates continue, not only in the art world, but also in Parliament whose resolution is a political decision that marks a new beginning in the relation between art and power. The fact that the decision to create the museum explicitly refers to “the permanent joining of the new currents and trends that appear in the evolution of the contemporary visual arts” but also to “the promotion of new esthetic behavior” represents the first victory over power. But it is also an indication that Romanian political society has grown and is now capable of digesting the most astonishing contemporary art projects. The Positive Some major objectives have been attained through this project. A positive precedent has been established through the architectural conversion of the House of the People. The new space is human, spectacularly contemporary and in striking contrast to its neighbors. In the coming years the Parliament will likely opt for additional architectural alterations in this town-sized building; the difference between the museum and the rest of the building simply needs to be made less disturbing. The first comparison that comes to mind is just that: Imagine a divine diva next to an overdressed old lady injected with Botox! Also, although humongous and cumbersome, the space is also one that seduces through its monstrous history. Several well-known international artists have expressed interest in exhibiting their own Utopias in Ceauşescu’s edifice—in a space originally designed as a Utopia by the most uncultured of European dictators. In addition, the debates in artistic circles have had a healthy role, as the needs of the artistic community have been made public and explained to everybody. This mass brainstorming has finally generated artistic movements of national proportions. These convulsions are a sure sign that in Romania we are witnessing a true evolution in contemporary art. A youth biennial accompanied by an international symposium has preceded the opening of the Bucharest museum, another international symposium and a series of exhibitions have been organized in Cluj, and an international exhibition opened in Iaşi a little while ago. All these events say a lot about the interest and desire for open competition among artists, curators and managers in the Romanian artistic milieu. Some Romanian curators insist on importing curators and artists in order to provide the Romanian space with content. However, the exhibitions organized by the museum, on the occasion of the opening, speak for themselves. Tributes are paid to two great artists emblematic of 70s Romanian art both of whom have recently passed away, Horea Bernea and Paul Neagu. The presentation was appropriate. The exhibition curated by the general director of the museum, Mihai Oroveanu, reconfirms the artistic value of the real dissidents during the toughest period of the Ceauşescu dictatorship. Although there was some suspicion about this exhibition – it was derided as either simplistic or documentary – the re-establishment of the rights of those who have directly contributed to the development of the artistic climate and expression during such a troubled period in terms of ideology is the museum’s first obligation. One cannot understand the art world without having seen works of earlier modern Romanian artists that had been hidden and inaccessible for so many years. The exhibition curated by Ruxandra Balaci, the artistic director of the museum, continues in the same vein as it presents representations of the House of the People in works by Romanian and foreign contemporary artists. Entitled suggestively “Romanian artists (and not only) love the palace?!” the exhibition explores this double rapport that artists have developed in relation to the “great foundation” made with the sacrifice of several generations. The fact that the building situated on the highest spot in Bucharest cannot be ignored, whether we like it or not; what follows is the management of the relationship to this colossus marked by multiple symbols. As evidence, all the artists presented in the exhibition manifestly express a position regarding these symbolic strata relevant to the artistic level, and the result is an exhibition that cannot leave the viewer indifferent. At least some aspects, hidden until recently, of the House of the People are revealed. The projects of well-known artists of the 90s are noteworthy: Dan Mihaltianu, Teodor Graur, the Subreal group with their project The Castle in the Carpathians. Also individual projects by Iosif Kiraly and Calin Dan (members of the group), Ion Grigorescu – “Dialogue with Comrade Ceauşescu,”, or the projects of some very young artists including Vlad Nanca, Stefan Cosma, Irina Botea, and Alexandra Croitoru. The international exhibition was organized in collaboration with the Modern Art Museum of the city of Paris, the Palais de Tokyo (also in Paris), and the participation of major curators such as Obrichts and Nicolas Bourriaud, as well as with well-known international artists. Such participation demonstrates the interest that such a museum, in such a location, can inspire within the European environment. If the image capital is to be fully exploited, we might witness in the future spectacular projects that can take advantage of all the eccentric aspects that make the House of the People so unique in the world. The Negative No doubt the opening of the MNAC means much more than a cultural project. It is the victory of the free spirit against local conservative mentalities. However, as is true of any pioneer project, it won’t be easy to manage. The fact is that the museum hasn’t got an approved budget, and the technical team of the museum isn’t prepared for large-scale events. This makes administrating the work even more difficult. Reform has to come from the inside, from the managers who must impose their viewpoint and their quality standards in a much more responsible manner than they are accustomed. But is this possible? That’s the rhetorical question raised in the art community. Isn’t that just another Utopia? MNAC is not MOMA, nor will it receive the budget that a similar European establishment automatically expects. It is also true that the artistic environment is not sufficiently ripe, so we can expect other controversies and debates in the future toward developing a true movement of values and opinions. This is absolutely necessary for finalizing the evolutionary process of Romanian society.

01.04.2004

Artículos recomendados

|

|||||||||||||

Comentarios

Actualmente no hay comentariosAgregar nuevo comentario