| Umělec 1999/5-6 >> Alfred Kubin - A Few Notes Inspired by the Exhibition | Просмотр всех номеров | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Alfred Kubin - A Few Notes Inspired by the ExhibitionUmělec 1999/5-601.05.1999 Otto M. Urban | artist | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

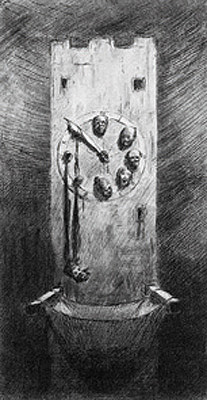

One of the oldest preserved works by Alfred Kubin (1877 - 1959) dates back to 1883. The pencil drawing is entitled Magician - the six year-old Kubin depicted a witch gathering full of levitating demons, bats, snakes, skeletons, even a coffin, a royal crown, military medals, and bishop’s staff, etc. The technical aspect of the work does not surprise one very much as it corresponds with Kubin’s age and talent. What is unusual about it is the content concept of the drawing which goes far beyond infantile illustration of a scary tale. The drawing reveals the fresh student’s wild fantasy, combining both secular and religious motives and ironic hints at money and the world of capital. All of this is permeated with hermeneutic and masonic symbols. The figure of the magician, with his arms spread helplessly and sad expression in the face, looks more like a monk or a priest suffering from neurosis. The chaos starts, the magician lost his powers and is not able to call the demons back, the world begins to live in a wild rhythm of its own effervescence and madness. It is not the magician but everything that surrounds him that is the embodiment of evil, poverty and perversion. Kubin’s own identification with the magician, his powers and fatal sadness as well as his ability to see, to be a voyeur, seem obvious.

So who was Alfred Kubin? Such question comes to mind of everyone who has ever came across Kubin’s work. Who was the maker of such visions of hell and limbo? A laconic answer could be as follows: Austrian artist and graphic artists (he illustrated books by Thomas Mann, Edgar Allen Poe and Gustav Meyrink), author of one single novel and a remarkable autobiography, associate of the expressionist group Der Blauer Reiter, and in Bohemia we would mention that Kubin was born in the town of Litoměřice (where he only lived for two years) and his relationship with the Czech environment was not uninteresting. Often mentioned is his liking in decadent symbolists such as Odilon Redon, Félicien Ropse and James Ensor. It is Ensor who seems to be the closest to Kubin’s perception of the world. Kubin appreciated his sense of irony, or better yet bizarre sarcasm. The combination of low and high, poverty and wealth, glitter and filth, courage and fear, grace and awkwardness provide suitable situations for their characters revealing the strangest vibrations of a human heart. For Kubin (or a bit earlier for Ensor who shared obsessive interest in human excrements with Kubin), the world seized to be a fatal and utterly serious issue, or the issues it was bringing up were more ridiculous than serious or ridiculous despite their seriousness. The place of love alone is somewhere between cloaca and a latrine, the noble is demeaned, insulted, ridiculed, only fear and suffering still bear some seriousness and mystery. Even that, however, begins to fade away for Kubin, a pessimist of Fedor Sologub or Ambroise Bierce type. Here is how Kubin remembered of the period when he was working on The Land of Dreamers: “I came to realization that the highest values of being lie in bizarre, noble and comical moments and also that what is awkward, everyday and incidental comprises the same mysteries (...).“ Meaning: mysteries of real life and existence that are stripped off their mystical dimension but gain in everyday pain which is as awkward as ubiquitous. Kubin resolutely rejected simplifying allegoric approach and has begun to drift away from complex symbolism of early modernism during the first decade in order to draw near to voyeuristic poetics of decadence. To see and to reveal while not being seen doing it. Fascination with a detail is as important as pursuant awkwardness of the moment. A few decades later, both would see their film counterparts in opuses shot by Georg Romero and in Georg Ligeti’s opera La Grand Macabre. Fascination with the low, studying it and describing it and sentimental liking for it permeate modern culture in all directions. Pulp genres, kitsch, mass entertainment are accepted by modern art much warmer and with much understanding compared to previous epochs. They become some of the basic sources of inspiration, surprising refreshment in a new context. Kubin does not create real worlds, yet his most bizarre compositions take on appearance of reality, obscured behind a veil of fatigue, hallucination and neurosis which are present in every element, atom, and cell. Kubin is not usually included in conventional text book surveys of modern art, he’s a bit off. He has never belonged into traditional interpretations and perhaps this is the reason why he became one of the most influential artists of the 20th Century. Not many artists have enjoyed and still enjoy such continuous attention and so many direct references. A number of artists take inspiration in Kubin’s work: Roland Topor, Arnulf Reiner (who also appreciated Kubin’s drawing technique), Franz Blaas, Vladimír Kokolia, Joe Coleman, Francis Bacon and Joel-Peter Witkin, etc. Even forty years after Kubin’s death, it is thought-provoking and exciting to sink into his visions, becoming part of them, explore mysterious corners in peripheries, fight scary monsters, hell around with demons and tramps at apocalyptic parties, watch natural settings and underwater forests just so we can find a way into the bizarre dream of the city of Pearl where everything is a rebour in the end anyway.

01.05.1999

Рекомендуемые статьи

|

|||||||||||||

Комментарии

Статья не была прокомментированаДобавить новый комментарий