|

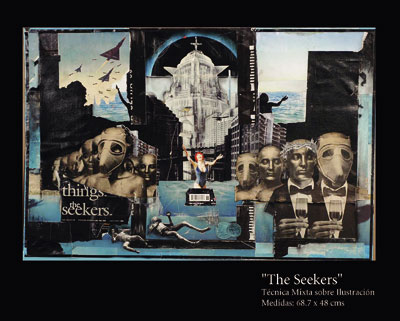

No art is more easily recognizable to a traditionally Catholic town than religious art (this in spite of the damage the said religion has suffered due to the proliferation of church-sects that have robbed it of vital space throughout the years). The hordes that overstuff the churches every weekend have accustomed their eyes to the rather gory paintings and sculptures of bloody Christ carrying his heavy cross with a crown of thorns and an expression of physical and spiritual pain on his face. On occasion, if the celebration calls for it, these same people carry Zarzales on their backs, while thrashing their backs and scraping their knees in search of an epiphany. Other times they convince their own kids that they should kneel and try to travel all the way to the temple in that position; therefore, they’ll have something to be thankful for, or to ask for, once they arrive. In good measure, these liters of blood and gestures of pain (plus redemption) have been the aesthetic education of one of the most fervently catholic cities in Latin America. But the aesthetic eye of Catholicism has been shaped by many other situations, each one more bizarre than the next. As with the iconography of church altars, aspects of the catholic faith include votive offerings—homemade altarpieces with delirious miracle scenes of the disabled returning to walk, the alcoholic finding sobriety, and the beaten woman pushing the demon out of her husband. And there are the Miligratos—medals that vary in size in proportion to some desire and are used to help beg a saint to be the intercede with god for various miracles to cure disease or find a stable partner. Also, there are religious picture cards containing images of different saints, virgins and demi-gods in multicolor kitsch designs outside of church, or, with luck, in subway cars, distributed by street kids, drug addicts in rehabilitation, or carriers of HIV, and which are the routine amulets of believers. Altogether, it’s a cult of images that posses not only a religious charge but also the ideology of the belief itself. In that way any passerby can, in a pop transfiguration of the myth of San Juan Diego, can, if providence permits it, become the newly chosen one to take on the voice of the Guadalupano miracle worker. A wormy plank, a vinegar stain on the pavement, a formidably shaped cloud—anything that can be converted into a new altar, in a new ceremonial center for the masses perpetually looking for the Promised Land (even if this can be found in an underground tunnel). The same devotion and the same faith can be found as a new message in the extreme religiosity of the present as represented in the art work of Ernesto Muñiz. In his art, Muñiz has evoked distinct parts of Mexico City. His pieces – “Guerilla Shrines” as he refers to them – are collages. By unifying different objects, he deconstructs images and creates new symbols that become a commentary on the Catholic religion. The message, at least at first sight, isn’t hidden behind any elaborate and exhaustive discourse. Simply put, Armageddon appears to wait in heaven and God’s soldiers are the messenger. However, like some military nightmare from these mediated times, the message is unreadable through the smoke from bombs, because the messengers of destruction can wear masks that protect the rarefied air; Jesus (of the Sacred Heart) carries a weapon, and it is not known whether the imminent end of civilization motivated him to hold up a convenience store in a panic or if he just wanted to get stuff easily –and for free- by pointing his gun. Saint Hyppolite – known as “the first anti-Pope in history” - also goes out into the streets, where he pays for a prostitute. The annunciation is a phone call. Muñiz’s work is found at the indeterminable intersection of urban intervention and street art. While local artists who cultivate this last discipline tend to depend on aerosol, posters and decals, the world of Ernesto Muñiz breaks the rules of guerilla warfare with the intention of being a little bit more confrontational. He does this by constructing ephemeral anti-altars whose messages have a force and clarity that leaves no room for ambiguity. He also experiments with the collage as a medium, expanding his graphic possibilities. The passing of time (at times not even necessarily long periods), gives the pieces an effect desired by Muñiz: the collage’s initial role erodes as passers-by paint over it and the climate continues changing its original appearance. This either hardens the original message or mutates it. Muniz’s collages function as apocalyptic homemade altarpieces; his saints have lost faith, or at least they are shown in their total cruelty; they teach the bloody claws and eyeteeth, with traces of the meat from their prey. The virgins are virgins through denomination, but their purity is promoted by necklines, and they carry arms and live in danger. New miracles should be more shocking or they won’t be considered miracles, not because the town has become jaded and nothing can impress it, but the opposite: the new faith has charged a quota of sacrifices, each one larger than the last, and the deities continually require more of the parishioners, but themselves ask from apparitions which quiet the breath, and if possible, the pulse. In this way, sanctity becomes more human, and because of this, more vicious, more violent and driven by impulse and instinct. There is nothing more to save than your hide. The faith reflected in Muniz’s representations retains a syncretic nature. Elements of traditional religiosity are joined to those of contemporary (violent) life.

Рекомендуемые статьи

|

|

We’re constantly hearing that someone would like to do some joint project, organize something together, some event, but… damn, how to put it... we really like what you’re doing but it might piss someone off back home. Sure, it’s true that every now and then someone gets kicked out of this institution or that institute for organizing something with Divus, but weren’t they actually terribly self…

|

|

|

Nick Land was a British philosopher but is no longer, though he is not dead. The almost neurotic fervor with which he scratched at the scars of reality has seduced more than a few promising academics onto the path of art that offends in its originality. The texts that he has left behind are reliably revolting and boring, and impel us to castrate their categorization as “mere” literature.

|

|

|

Goff & Rosenthal gallery, Berlin, November 18 - December 30, 2006

Society permanently renegotiates the definition of drugs and our relationship towards them. In his forty-five minute found-footage film The Conquest of Happiness, produced in 2005, Oliver Pietsch, a Berlin-based video artist, demonstrates which drugs society can accommodate, which it cannot, and how the story of the drugs can be…

|

|

|

There’s 130 kilos of fat, muscles, brain & raw power on the Serbian contemporary art scene, all molded together into a 175-cm tall, 44-year-old body. It’s owner is known by a countless number of different names, including Bamboo, Mexican, Groom, Big Pain in the Ass, but most of all he’s known as MICROBE!… Hero of the losers, fighter for the rights of the dispossessed, folk artist, entertainer…

|

|

Комментарии

Статья не была прокомментированаДобавить новый комментарий