| Umělec 2002/3 >> Jesus in Venice (interview with René Rohan) | Просмотр всех номеров | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Jesus in Venice (interview with René Rohan)Umělec 2002/301.03.2002 Vladan Šír | q & a | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

"A project by the group Kamera Skura (Martin Červenák, Jiří Maška and René Rohan, est. 1996) from Ostrava, CZ and Slovak artist Erik Binder won the competition for the joint Czech-Slovak pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2003. This is the first time in recent history the jury selected a proposal submitted by artists without representation by a curator. During a day-long session on 26 September 2002 the committee selected from the eight projects that made the deadline and requirements set by the National Gallery in Prague. Italian organizers have announced that the theme for next year’s biennial is Dreams and Conflicts. In an interview with Umělec, René Rohan from the group Kamera Skura describes the winning project and talks about preparations for the joint pavilion.

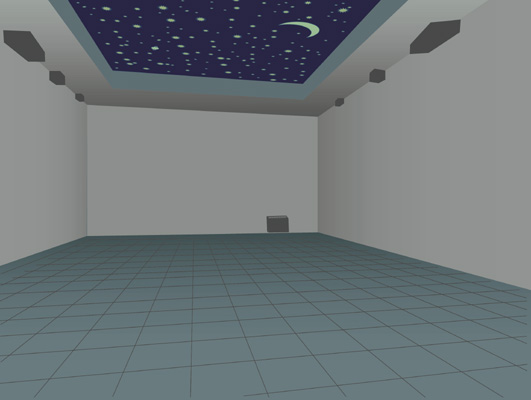

What made you apply for participation in Venice after all the horrors Jiří Surůvka went through last time? Surůvka experienced horrors because he teamed up with [Slovak artist] Ilona Németh. They were both personalities that could make individual project in Venice, but together they were unable to compromise. So he basically made the horrors for himself. We decided to make a project with Erik Binder, and we really created it together and presented it together. Now we will also make it together. We can’t wait. What I had in mind was cooperation with the National Gallery, which in previous biennials has allegedly failed to provide full services. To a certain extent, it’s also thanks to pressure I created that [the competition] was announced and completed before November. So there’s still time to apply for sponsorship from big corporations, and there’s still time to do a lot of work. Every Biennale there’s a problem with the Venice catalogue. It was difficult to present the projects because you found out who won in March. The project then has to be produced, photographed and then made into a catalogue. Another problem was that the money [from the Ministry of Culture] was decided in June. There was always this time problem, which now isn’t so crucial because we can already begin to work on the project in October. Another thing is that [curator] Michal Koleček is now working in the National Gallery [see p. 19]. Cooperation with him will be wonderful. He is an extremely capable man who enjoys and understands our work, and he’s got great organizational skills. He’ll be in charge of Venice. This is another plus that made us join the competition. Furthermore, I’ve worked on the organization of two Venice Biennials together with Jan Černý [from defunct MXM Gallery], so I know what the work is about. Nobody else could be talked into it. We’ll do everything ourselves. What do you mean that because of the pressure you created the competition was announced earlier than it had been in the past? Two years in a row there wasn’t enough money for Venice; two years in a row we organized it and two years in a row we were pressing and pushing for the competition to be announced earlier, for the committee to meet earlier and the results to be announced before November, when big companies close their books, because after that there’s no chance of getting extra money. A small company that isn’t international doesn’t care about some exhibition in Venice. It has to be a company with international credit. Isn’t it a conflict of interest that you coorganized two recent exhibitions in Venice, and now you have submitted your own project? I’m not an employee of the National Gallery, and I’ve never been one. I did production for artists, because they were incapable of organizing it themselves. Now I just produce my own things. I’m not an employee of the National Gallery carrying out my own projects and realizing them in the name of the National Gallery. This would be a conflict of interest. Plus the competition was anonymous. When did you decide that you would join the competition for Venice? We’ve always thought about what we would like to do. We rejected the Chalupecký Award and didn’t want to apply for that. Competing in the arts seems ridiculous to us. We’ve been invited several times to apply for the Award. But the composition of the jury itself affects who’s going to be the best, which we think is totally wrong. Let’s say that the committee was composed in such a way that we had a chance to win… But we still wouldn’t do it. So we thought: “Let’s show that we’re not afraid to compete with the top Czech artists.” So we decided to apply for Venice, and there we would compete with the world. So we applied, and it worked out. The National Gallery advertised the competition on August 26 and the deadline for applications was September 25. Is a month enough time to prepare an entire pavilion? Everybody was surprised by that. I didn’t know that it would be so soon. I picked up the form on September 6 and only then I found out that the deadline was September 26. So we immediately called a meeting with Kamera Skura and Erik Binder, because there was no time to waste. We put together the project, as it was already prepared, but we had to start on the presentation for the committee. So you had the project prepared beforehand? We had a project thought out, but we hadn’t intended it for Venice. We wanted to put it up in the Hall of Veletržní Palace in the National Gallery. We were invited by Michal Koleček to make an exhibition there. When the Venice Biennial was announced, the theme fit like a glove. It was all we’d hoped for. So we partly finished the project and partly changed it to meet the requirements and we were done in one weekend. We had no idea what the theme was going to be when we made it, but it turned out to be ideal for our project. Was the fact that you worked on the project with Erik Binder also an accident? It was a huge accident. We liked him before though. We’d meet up with him pretty often — we exhibited together in Ostrava, Košice, Žilina… I know him personally; the other guys know him a bit less, and he’s extremely funny and witty. When he made the notice boards for the Young Biennial in Prague two years ago, we couldn’t stop giggling. In Ostrava he exhibited a sort of punk sweater — a torn sweater with a sign in thistles reading “punk.” We usually say when we see his work, “Too bad we didn’t come up with something like that ourselves.” Gábina Bukovinská [from the Center for Contemporary Arts in Prague] once suggested an exhibition with Erik Binder in Gallery Jelení [as part of the exchange program between Jelení and the Center for Contemporary Arts in Bratislava]. Clearly they also thought that the things we were making were close and could work together. So we said, “Sure, anything anytime with Erik.” So it was an accident. What will the pavilion look like then? There will be a figure of Jesus hanging in the rear third of the pavilion, lit up with a spotlight in a theatrical way, just like in a church. But it will be clear that it’s an athlete performing on the rings. His head will be tilted in a way that athletes on rings would never do, because that would be a mistake. He will also have long hair — athletes usually have short haircuts, so that their hair doesn’t get in the way. The pavilion will be dark. Originally, we only had the Jesus. We made photographs and thought that it would be a really cool thing if we could have an entire figure in Venice. Then we said to ourselves: “An empty pavilion with only one three- meter-tall figure? That’s boring.” So we told Erik about our idea and together we came up with the final look of the entire exhibition. Erik brought ideas that will make the whole thing a lot of fun. On the walls there will be a projection of an audience that will cheer madly like a noisy football audience, and suddenly the atmosphere will change and you’ll be able to see an audience watching something like a chess tournament, staring at the chess players in silence and tension. We will go to sporting events and shoot the audiences. It will be a detail shot with only people in it so that it’s not clear what kind of sporting event it is. And with all that it’ll look like the athlete on the rings is sleeping. It’ll shift over into nonsense. The ceiling will be covered with black canvas and there will be stupid little stars, a childish moon, planets and Bethlehem star painted on it with phosphorescent paint or light yellow, which would be lit with purple light. The straps Jesus will be hanging on we’d like to make a little dark so that it looks like he’s suspended from or being pulled up to heaven. The entire scene will be dreamlike. There will be an enormous conflict between the soul and the body. Jesus, the embodiment of spirituality, will be in an extreme sporting pose. Not only that, it’s a pose a normal person couldn’t possibly maintain. The theme of conflicts and dreams gave us the space we needed to make this project. What’s the budget at this time? The Czech party has promised something up to a million crowns; the Slovak party will chip in something too. We also want to address sponsors. I had a meeting at the National Gallery where I was told that we underestimated some things in the budget, so we’ll have to make some changes. Production costs should be about a million crowns. If we want some extra things, we’ll have to look for sponsors. We came up with a lot of things that we’d like to use to make an extra program, like souvenirs and a billboard on the pavilion, which were not part of the original budget. We didn’t even think we’d win, so we’d only calculated for the project itself. Now we’re coming up with all these things, and it just might turn into a circus around the pavilion over the next nine months. We’re thinking of souvenirs, things that people could take away so that the pavilion is promoted as much as possible. We might also have advertisements, posters and perhaps billboards. There’s nothing like this in the budget at the moment. At a meeting in the National Gallery we realized that it would be worth it — at least posters in trams and the metro. It’s just such a shame that the Ministry of Culture and the National Gallery give so much money for something that is hardly advertised in the Czech Republic. It’s money thrown down the toilet. In the Czech Republic it’s a big thing only for those who exhibit in Venice, or maybe those who happen to go there. Otherwise, nobody else knows about it. The Gallery itself is not even promoted. It’s for the sake of both the artists and the Gallery, to raise awareness of Venice here and to promote it as much as possible. Promotion, however, could end up costing more than the production of the entire project… Yes, it could. That’s why we want to look for sponsors for the additional activities. Now that you won, what’s in store for you in the coming months? Now we’ll meet with Erik and celebrate and then we’ll start working. Since the competition was announced early, we’re counting on the fact that the National Gallery has some reserves that could be drawn on this year. We’re trying to organize things so that the money for production of the figure is set aside this year and we can start working on it. We don’t have the money to make a three-meter figure cast in fiberglass. Then we have to try and find a space similar to the pavilion where we could install it. We’d like to finish the entire project by March: to have it tested, ready, finished and photographed for the Venice catalogue. Then we’d like to put together the catalogue, which we’ve already printed once, and make a catalogue for Erik Binder. The one we made is already paid for, including the photographers, translations, so the National Galley will save a lot of money on that. Erik Binder is working on his catalogue himself. We’ll make an additional print run of our catalogue including the organizers’ logos and we’ll add about 20 pages. By November the project should be visually strong so that we will be able to present it to sponsors. We have so many things to get done before the end of the year, so that we can make everything without any compromises. "

01.03.2002

Рекомендуемые статьи

|

|||||||||||||

Комментарии

Статья не была прокомментированаДобавить новый комментарий