| Umělec 2008/2 >> Q: Against the Current | Просмотр всех номеров | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Q: Against the CurrentUmělec 2008/201.02.2008 Lenka Vítková | profile | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

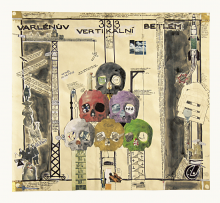

I am constantly striving to arrive at the moment of zero in art. Neither plus nor minus. Neither too much nor too little.

IKW Whilst I have been laboring over these words, Igor Korpaczewski has been keeping busy. When I first met Igor to look over some prints, Korpaczewski was exhibiting in the Resetting show Prague’s City Library gallery. At the time when the text was supposed to come out, he was based at Prague’s Meetfactory studios where Q: had set up the huge Wake-up! environment. Whilst writing this, Q: is installing Starstop at the Benzinka gallery in Slany. But the artist is still thought of as one who leads a relatively solitary life and gives public presentations with the efficiency of an introverted perfectionist. The idea to look at all of Korpaczewski’s installations in a single essay came to me when Igor and I were arranging Q:’s exhibition at the 36 space in Olomouc, a gallery which I curate. During several long telephone conversations before the Sen Insomnie (Dream of Insomnia) exhibition, I felt as though I could visualize all of Igor’s previous installations. It was as though one of the conditions for setting up the exhibition was to have a thorough documentation of the previous works and at the same time an equally thorough “freezing” of all his unrealized projects. Language and the silent machines Igor Korpaczewski is KW. He is also Q: or IKW, depending on the situation. “I had the feeling at the time of Konfrontace (Confrontations), which was in 1990, that I would really prefer just to have a number or simply some sort of symbol,” he explained, adding that he chose KW, which his mother used as an editorial mark for corrections or translations. “At the start of the millennium, I said to myself that I should get rid of KW, but I wanted to keep the sound of it.” Since 2001 he has been using Q: for work in three-dimensional space in order to differentiate from his other works, mainly paintings, which are signed KW. The Resetting exhibition, which was set up at the beginning of the year for the Prague City Gallery’s City Library branch, by curator Petr Vaňous and artist Petr Malina, featured similar styles of paintings alongside each other and in this way the emphasis was placed on the techniques used in their creation. Works with the signature KW or Q: were to be found throughout the exhibition, and stood up well in this context. In some works, cars substituted for figures. For the artist, the automobile merits the status of a being: he imbues it with expressions, and silence; he shows existence on the borders between the living and non-living, where behind the dark, opaque windows, life flickers within. A car without a steering wheel is an unambiguous metaphor. Korpaczewski’s paintings created their own space not least because of the tension between the canvases and their titles (KW A Spell of a Drug, 2007; KW: Enjoy Your Life Experience, 2007, KW: I say: Danger!, 2006) which suggest novelistic themes. Korpaczewski seems to have some kind of established system for classifying perceptions in which a stockpile of motifs helps to expand, and then employs a poetic principle in their organization. I don’t mean by this that it is stated in words. I mean the way in which he places objects and paintings into the installation and allows the meaning to emerge from among them. In the construction of a novel, it is the psychological state of the character, the solidly constructed personality, whose interaction with other characters or situations propels the plot. When he talks about his paintings he speaks about language, the novel and poetry--and the ones and zeroes with which he encodes his message. His paintings are built up from daubs of paint; he is more of a draughtsman than a colorist. When we look at paintings in this manner, it becomes a logical step to move on to three-dimensional space. The pictures, objects and texts all carry weight in Q:’s painting installations and therefore go beyond the theory that, “the picture is the superior thing, whose sole raison d’etre is that everything occurs within it and nothing surrounding is of any importance…” In painting installations, these links are not descriptive, but they create a complex structure – and at the same time they are constantly disintegrating. The original material or source is absorbed or duplicated through the content. For me, Korpaczewski’s works always have a clear border of readability--a moment when, after long hesitation, brushstrokes or elements of an installation bring together the picture or meaning. The manner in which the paintings or installations are assembled is important for their content. It is thanks to this that we are able to appreciate what we see in front of us. This constant transformation of the material in the picture and of the picture in the material lends Korpaczewski’s pictures a dynamic that paradoxically strengthens its meaning as though by consolidation. The novel cannot continue and all the possibilities of the subject remain within and are not ruled out by choice or by an exhausted narrative. On the painting Disappearing: “I had the psycho-physical feeling that the atoms split apart, it was here in these areas that I painted the drums and then the portrait over it. Then I did variations, I had a mirror and I painted myself with the drums in the background – but it wasn’t strong enough. I wanted it to have more mass, to be sharper… The final version is Cezanne-like… In place of glaze I painted a layer of varnish over the drums. I tried to decipher the painting…I know what I want and don’t want to know how to do it. I have to read it through in 2D so that I can read it in 3D--something that doesn’t have anything in common with real space. It’s as if I’d mix together those zeroes and ones long enough for something to emerge.” I decided to leave in the text this resonating quote from the conversation during which Igor explained to me his inspirations and aims in connection with the contents of his works. But it seems to me just as adequate to simply consider that which is visible or – for me – brings attention to itself. Stella Maris The Stella Maris project (1998) was exhibited at the JNJ Gallery in Prague in 1999, in the U černého pavouka Gallery in Ostrava and in the Titanic Gallery in the Theatre of Music in Olomouc. Pictures on canvas and on plastic boxes and smaller polystyrene objects were accompanied by short texts (on pages 26-27). Everything was arranged in a row and you could read from right to left. Korpaczewski attempted a story “materializing into the objects, converted movie stills.” “A photo of a black boat around which small steam boats are all sailing away, at the start.” The pictures capture the captain and his wife, while the objects from cellophane and polystyrene give a view through to the mechanical organisms, to the submarine. “The boat symbolizes his life. The more he wanted to connect, the more he was alone.” The story of the captain of the boat who avoided rescue and ended up at the bottom of the sea, is strung on a few small fragments, pictures, objects – medicine balls from Martin Horák’s shed, gloves from a play, objects associated with childhood. A knife on a red bar, sewn under blue plastic cellophane, points to the psychological suspense in Polanski’s’s film Knife in the Water. Korpaczewski said that it was important for him to have found some of the objects rather than having made them himself. Frutti di mare was introduced as a kind of prologue to Stella Maris. There are pieces of artificial materials (the bottom of a bucket and so on) washed up on the Italian coast, from which emerge faces drawn in felt-tip pen or using a paint-filled hypodermic syringe. In the JNJ Gallery they hang attached to a wire like small rare gems on a necklace. “It is something that would be somewhere in the depths, then it rises and within it still has some kind of surface.” Korpaczewski arrives at his themes in a similar way to his creations. “When I try to explain how I do something, I always ask what its origin was and where the circumstances were leading me. For example, my girlfriend was asking me what use there is in a God that allows Auschwitz to happen. That led me to Young Gods (painting series, 1996) which, without meaning to, took on a comical aspect in which God was an action hero. The Young Gods come from the opposite direction, not from heaven; today they can come from the gutter. Or an empathetic God-superhero who can shed tears but also acts.” Stella Maris was the first project in which Korpaczewski used the gallery space to relate a story, and he improved on several innovations which he had used previously – eg contrasting materials: “Plastic meets classics” was the name of KW’s exhibition at Prague’s Radost FX gallery in 1995, where he exhibited paintings wrapped in clingfilm and framed in a polystyrene molding. The title touches on the principle which runs through KW’s work – a meeting of highbrow and lowbrow. He does this out of necessity and not through flippancy. It is a movement on the boundary where existential meanings in the post-postmodern world flip over and become lost, a movement on the boundary which for the author is the one and only legitimate path. Korpaczewski uses classic techniques and grand themes as though he would like to prevent their devaluation, their preventive “pre-devaluation” that at the same time brings attention to their misuse, relativity, to the loss of innocence when using them. “I made a girl out to be like a vampire, and the way the blood is, it isn’t clear if the blood is flowing inside or out, if she is bleeding or if she has sucked someone’s blood. It was called Dovnitř nebo ven (Inside or Out).” A series of paintings and drawings with the theme of levitation was exhibited in the gallery under the café Velryba entitled Extáze nebo trik (O umění) (Ecstasy or a trick (On Art)). “It was about art and about the fact that someone could have something very dramatic and yet at the same time could be inventing the whole thing, and that it isn’t all that easy to spot the difference.” In order for him to use his pictures as a medium for his ideas he has to employ opposites. He swims against the current. In the last picture from Stella Maris, entitled Perla (The Pearl), the captain emerges on the other side with a pearl in his mouth. Words are no longer necessary. Transparent In the Stella Maris installation in Olomouc’s Theatre of Music, on the reverse side of vitriny ve foyer (Display Case in the Foyer) a shining strip of snakeskin covered with black cellophane was hung up: Adamova pomsta). (Adam’s Revenge). The enclosed silhouette of a figurine from the 1930s could be seen through blue semi-transparent cellophane framed in a black mount into an octagonal shape slightly reminiscent of a coffin, revealing a dark figure. The portrait of a woman on a transparent plastic lid, the bottom part spray-painted and the top part made using acrylic paints and felt-tip pens, was photographed by Robert Portel surrounded by twisted textiles and plastic materials in larger plastic boxes in order to get the “chocolate-box” effect. Why are transparent or semi-transparent materials so important for Korpaczewski? They allow him to obstruct the view; they provide distance. The microwave plates covering the painting protect it in place of glass, distancing it from being a record of reality and bringing it closer to its essential character, for which techniques for painting on glass or stained glass are used. Polystyrene frames, protective cellophane, glass, mountings, lids from plastic boxes form the basis of the picture, which demands special attention; at the same time, the materials used place the picture in the present day. The individual marks of the painting are precious stones set in the background, like eyes – precious signs of life placed into the mass of the face. Shiny, transparent or other materials with optical effects give the illusion of movement to the brushwork. The dark, or more correctly, the twilight, plays a similar role to the semi-transparent materials. It delays our perception of the installation, and paradoxically emphasizes the values of the space, such as depth and spaciousness. The choice of lighting for parts of the installation allows Korpaczewski to organize the time-frame in which we perceive the installation. This optical screen, whether it is formed by semi-transparent material or darkness, prevents too much being given away. Peace on Earth The installation Peace on Earth was first exhibited in 2002 for the At Home Gallery in Šamorín, a former synagogue. “There was a beautiful painted ceiling, an incredible place, awaiting the touch of light, so it was all picturesquely shabby. And amidst this are pedestals awaiting the touch of contemporary art, which is what everything needs. So the first idea that hit me was I would seal off the windows – going against the current.” The subtitle – tableau vivant – a living picture, grasps the peculiar slicing between the second and third dimensions, a virtual reality from cardboard and plastic, which could only be seen from a corridor under the gallery through a small aperture in an artificially created wall. Iron steps with a banister led up to it, just like in a German U-boat. The windows were covered over, apart from the edges where tubes let in a diffuse light. On the sand-covered floor rested a five-meter-long boat made from reinforced cardboard, like a glued-together model of a warship, above which hovered plastic jellyfish. “During the first Gulf War I was holding a workshop in the Gallery of Youth and there were some people there from West Berlin. They were very much against Bush Senior and against the Americans, and I said how that was great, and that it would have been great in the 1980s if we had had someone to stand up to those Russians, Bulgarians, Poles and Hungarians. And then that post-revolutionary enthusiasm started to cool and you could see how bewildered the Americans were... And the logical outcome from all of this was ‘kóan.’ People will always attack other people and they will always defend themselves. And when will it end? When there are no more people left.” The small window under the gallery was covered by a layer of green cellophane and in the dark the ship seemed to be this enormous thing two kilometers down in the depths. Currents of air came from a fan in a corner of the room, causing the jellyfish to gently move, giving the picture life – a tableau vivant. The atmosphere in the gallery was enhanced by a short loop of a four-bar recording of a piano motif. The music was sad and in places warped, as though it came from those very depths. “The mother of the gallery owner thought that we had put water there and one art critic thought it was a video.” A picture formed on the principles of a diorama, but still a picture, albeit one which is constructed differently to a painting, shows how far Korpaczewski has come with his 3D work compared to the usual conception of installations. His spatial works stress areas such as virtual reality, but at the same time are grounded on the illusion being made with simple techniques. Korpaczewski reacted in a similar manner to Šamorín in an earlier exhibition space in 2001 at the Malá Špálovka KW exhibition of Bůh má oči všude (God Has Eyes Everywhere). “It was also a reaction to all those ironic conceptual exhibitions. I wanted to do a naïve exhibition. In the end I did a sort of little chapel. Pictures of birds on the walls, which are watching us – straightforward portraits – simply that the birds see us.” Korpaczewski transformed the exhibition space into something entirely different, as though the space was another being with whom the artist was working. Fighting girls Q:’s exhibition Diana from 2005 took into consideration both the purpose and history of the exhibition space in the actual installation. The café was originally called The Globe and had American owners. “In Ouky douky cafe I brought the pub into the exhibition – the décor brought into the café was in exaggerated pretend frames of the type used for hunters’ portraits…” There was a portrait of a girl with closed eyes emerging from the painting, while the “mantelpiece” assembly consisted of two pictures. In one of them a puritanical girl from the Wild West has laid down her arms, and in the second is a girl in the futuristic fighting costume of a superhero from a computer game, holding a bow. In between hung a blue cushion – the cushion was not there for resting your head on, but for duelling pistols. It strikes me that there is always something subversive about Korpaczewski’s female portraits – whether it’s their own dream of rebellion, or the artist’s rebellion against the genre of female portraits. A similar theme of female rebellion and a similar literal conception of space were used by Q: in 2006 in a lawyer’s office on Jáchymová Street where Dušan Brozman curated. “I came back from the mountains with Pavla, where the deer were roaring, and I didn’t want to go back to that way of working with offices, schools and so on, so I did the deranged secretary.” The installation goes in a clockwise direction and portrays a secretary as she is scattering paper on the ground - it is a drawing on glass, and cellophane is stuck on the ground instead of paper. Then she throws the pieces up in the air - it is a light silhouette cut out from polythene and stuck on clumsily almost on the ceiling. Then she leaves, dragging her coat behind her, her shoes left lying on the floor, she carries her trainers by the laces, and that makes up the drawing on the door. At the end there is a portrait locket turning in a lightbox, which has a contemptuous, calm look, and is probably that of Mánes. Solitaire Why does the name of the painter, Josef Mánes, always spring to mind? What is it about K’s work that makes it necessary to return to the first half of the 19th century? Why do I have sneaking up on me Moštěk’s picture of a figure of “great intelligence and subtle elegance” which became lost in grey clothes against a grey backdrop, because “he had never been obtrusive and had never imposed his personality on anyone”? Korpaczewski constantly touches on the classical, or rather what has become classical. The word “cult” could almost be used. He uses icons and iconic representation and then places them in areas where he senses a disproportion. Even the motif of the car in his works is reminiscent of the values displayed in “classic” American road movies, repeating the romantic vision of the free, yet lonely person on a journey. The belief in the communicative possibilities of the painted picture is shown by his forays into public spaces. “I would still like to make a friend over time” he writes in one of the Stella Maris texts. Part of KW and Q:’s success is that while processes such as fading, disintegrating and washing away are usually unwelcome, here they are tied straight into the concept, or are at least taken into consideration. In 1997, there was a competition to choose a project for Art in Public Spaces ’97. Proposals were submitted and then it was discovered that Prague city was not going to contribute a penny. Korpaczewski had proposed a painting of a girl for the Czech Legion House and the Medical House, who would be facing the main railway, looking up to the sky. “About a fortnight before it was due to start, the firm that had reconstructed the legionnaires’ house talked them into having this wonderful billboard. But I had already had plan B agreed with the owner of the house. After that year I didn’t want to do a girl… The title Timeman came to me on the fifth day in the tower. He watches time and follows time because time flies. American superheroes usually have names which stem from their capabilities or from what they manipulate, therefore - Mr Time…” Timeman is slowly becoming a shadowy figure on the façade of the Žižkov house where Korpaczewsi lives and works. Amongst his other works for public spaces is included Tvář (Face, 1997), which was exhibited temporarily at the Prague Trade Fair Palace. “It struck me that if it was inside the space and the painting was to be about some kinds of feelings, then it should be a small physical model of how things function in real life, that people make mistakes, they return and they either correct their mistakes or don’t even see them… And I was to do that on the spot at the opening. I had five large panels earmarked for me, the original was done on canvas, and then I painted all over the three large panels (without permission) during the course of the opening, and then I worked on them for another five days during the exhibition. I left plastic, paints, a stepladder and brushes there. The Trade Fair got me back though, saying the panels were actually from their store, so they painted over them because they needed them for another exhibition.” From the staircase window of the Žižkov town hall you can see a monumental scene that Korpaczewski calls “from the secrets of the Žižkov underground II” – a distillery of living water in a mechanical organism underneath Žižkov, a detailed spectacle full of activity, which paradoxically remains hidden from Žižkov’s residents. At Mariánské náměstí, prior to Communism there used to be a baker’s called Punčový řez (Rum Pastry). In this derelict and dilapidated building, two students, Skrepel and Sopek, held an exhibition. KW carved out a picture of a young man on the crumbling wall, stretching down from beneath the window to the floor. In Lisbon, on the wall of a house past which his friend would walk, he painted graffiti of a friendly alien with the offer, “Hi Juan, want a lift home?” Hold on I’m coming… Wake-up! In 2006 Korpaczewski blacked out the AM180 Gallery for the exhibition entitled Q: Hold on I’m coming. “The room was small, but beautiful because of its floor, easy to get to grips with. Most of the work involved getting rid of lots of things I had made so it wouldn’t be overcrowded.” A car and a phantom made from crumpled paper in overalls were imprisoned in a room painted on the wall, as if this non-existent room had been placed half a meter lower than the floor of the gallery and was about three times larger than the actual smaller gallery. The engine was outside of the car, which had no tires. A halogen light on the gallery floor lit a moving silhouette on a mirror-ball motor, which threw onto the opposite wall the shadow of a restless worker pacing up and down. The rhythmical movement of the light marked the passing of time in the dark room. “You want to achieve something and then you might say over the years, ‘just a little more time’…hold on I’m coming. In a self-ironic way I was looking at my own behavior.” The gallery space became a metaphor for the studio and inner life of the author/main hero. With the Wake Up! project (2008) Korpaczewski greatly expanded in scale the motif of a symbolic magic in an environment filled with shadowy corners. A titan lying under the sign Wake Up! subtly lit by light coming through a sealed window, an airplane and a view of a town shimmering from the depths on a wall, were all part of Q:’s exhibition at the newly opened Meetfactory. The enormous space comprising three halls will always be a challenging proposition for exhibiting artists. Korpaczewski worked for a month on site and began by heightening the intensity of the space by dividing it with plastic curtains and dimmed lighting. Even though the project Wake Up! was exhibited under the symbol Q:, it seems to me that this was more of a retrospective exhibition in which he brought together all his artistic techniques – installation, an autonomous painted picture or series of pictures, linked text, all of which were worked on with principles which could be used in public space projects. Some of the motifs used, such as the young god lying down in the first room and the implied continuation with Hold On in the dark third room, where apart from the artist’s car he himself also waits in a simple silhouette on the wall sitting on a tire, all of these opened the space up to reminiscences of Korpaczewski’s earlier works. Korpaczewski has a precise message for each installation, though the viewer does not have to completely decode this. Often it is simply impossible. It is perhaps more interesting to follow that which he leaves to be discovered in the sub-spaces of partial understanding, everything which he communicates from installation to installation. I am not thinking only of the spaces between segments of the exhibitions, but also the chronological delays between Korpaczewski’s individual presentations. For me personally in the Meetfactory there were two extensive wall paintings which dominated – a praying racing driver and, opposite him, a woman crying under a fruit tree, reminding me of the expulsion from Paradise. Here he used a style of painting and color reminiscent of paperback covers, where good triumphs over a clearly defined evil. Although the tears running down the girl’s cheeks are cut out of blue polystyrene, we believe that in the world of which his picture is a reflection, those tears are real. The idea of danger or of a threat to life is evoked in the picture of an atomic explosion, and he also comments on car accidents by using a newspaper article on the dangers of Formula One racing. It is as though a world is being presented where there is no safe place, and waking up to this fact is necessary. The call to Wake Up! can be taken as a message to the artist himself as well as the characters in the installation, which take on the form of Biblical figures in various relations to reality/waking: deep sleep, regret, faith, expectation, risk... (Or a combination – the racing driver Eddie? Jim Sachs prays at the start of the Indianapolis 500-mile Race, and puts on all his protective gear – helmet, gloves – and shortly afterwards he is killed in a car crash...”) The fate of the pictures was also quite apt as they were due to be destroyed after the end of the exhibition. These were of course linked into open structures in time, which create a recurring theme in Korpaczewski’s work. I respond Korpaczewski began his studies in graphic design at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague under Čepelák, where he concentrated on painting, then he studied under Václav Pospíšil. In age he belongs to the Tvrdohlaví (Stubborn) generation, but in reality the only thing he has in common with them is the decade of his birth. He mingles with people who are two generations his junior, but this does not mean that through his art he is attached to this generation. The link between him and the context of contemporary Czech art stems more from the fact that Korpaczewski reacts to this context in his own way and adds to it. “If there is too much of a tendency towards one pole, I feel drawn to the opposite pole.” As a “person who presents a classical format,” however, he feels the need for a synthesis, and even when he responds to or renews a situation, he brings the responsibility for his art to a kind of impersonal level. It is in connection with this that we can see why he uses a symbol – the artist simply sends out the hero KW or Q: to do his bidding… By locating his work in public spaces or galleries, he presents essentially classical values, both in the themes and the techniques. He does not hesitate to work in a contemporary context with an unusual seriousness – even though he uses irony and more often self-irony, it is not his goal to render everything ironic and therefore to constantly doubt, rather the opposite. This seriousness and absence of irony could be his main theme. Whether as KW or Q: he convinces that it is possible to put forward serious ideas in art. And even if his work is not immediately unambiguous and easily understood, he is creating space for a serious message and weighty themes. Music works in the same way. Igor Korpaczewski systematically devotes himself to it (for example the group Ich-forma or the earlier solo project Clean Dirt). Just as it is difficult to set out on paper the experience of Q:’s influence on a three-dimensional space, it would be difficult here to capture the atmosphere of one of Korpaczewski’s shows. It is certain however that the music comes from the same source as Korpaczewski’s work in the language of visual art.

01.02.2008

Рекомендуемые статьи

|

|||||||||||||

|

04.02.2020 10:17

Letošní 50. ročník Art Basel přilákal celkem 93 000 návštěvníků a sběratelů z 80 zemí světa. 290 prémiových galerií představilo umělecká díla od počátku 20. století až po současnost. Hlavní sektor přehlídky, tradičně v prvním patře výstavního prostoru, představil 232 předních galerií z celého světa nabízející umění nejvyšší kvality. Veletrh ukázal vzestupný trend prodeje prostřednictvím galerií jak soukromým sbírkám, tak i institucím. Kromě hlavního veletrhu stály za návštěvu i ty přidružené: Volta, Liste a Photo Basel, k tomu doprovodné programy a výstavy v místních institucích, které kvalitou daleko přesahují hranice města tj. Kunsthalle Basel, Kunstmuseum, Tinguely muzeum nebo Fondation Beyeler.

|

We Are Rising National Gallery For You! Go to Kyjov by Krásná Lípa no.37.

We Are Rising National Gallery For You! Go to Kyjov by Krásná Lípa no.37.

Комментарии

Статья не была прокомментированаДобавить новый комментарий