| Umělec magazine 2008/1 >> BalkanBeats | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

BalkanBeatsUmělec magazine 2008/101.01.2008 Robert Rigney | world | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

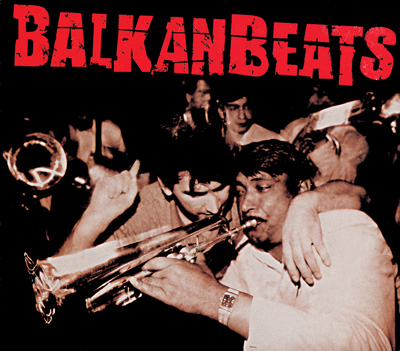

Mudd Club, Berlin

Bosnian DJ Robert Soko spins a medley of fast-paced Balkan Beats—Serbian Gypsy brass like Boban Marković mixed together with some funky Romanian manele from suburban Bucharest, and the crowd is going wild. Three Balkan chicks dance a whirling kolo while a group of Scottish tourists in kilts whip it up on the stage. All of a sudden it’s ‘Djurdjevdan.’ All the Yugos in the house go into ecstasy, linking arms and hugging one another. Everyone swigs at a bottle of slivovitz as the plum brandy begins making the rounds—just another night at the Mudd Club. Robert Soko, who has been putting on his Balkan Beats parties in Berlin for a number of years now, was the first to coin the term, Balkan Beats, in order to somehow define the mix of music from the Balkans, Serbian Gypsy Brass, and ethno-rock. They are folk melodies reinterpreted, given electronic beats, and blended with western styles like ska and reggae. In the recent past the phenomenon has caught on in other cities around the world where Balkan immigrants live. Balkan Beats parties are thrown all the way from Frankfurt and Vienna to New York and Melbourne. Mostly it’s immigrant Balkan DJs spinning sounds from their motherland with a western twist. Regardless, central to the sound is the music of Balkan Gypsies. No party is complete without tracks by Boban Marković and Fanfare Ciocărlia. While in Frankfurt the phenomenon is known as Bukovina Club and in New York its called Gypsy Rock, an all-inclusive label has yet to emerge—even though this world-wide community of Balkan, in the loose sense of the term, DJs and musicians do have a sense of stylistic unity. Mainstream acts like Basement Jaxx even got in on the act when the British duo incorporated Balkan horns on their recent "Crazy Itch Radio" album and released on their own label, Gypsy Beats and Balkan Bangers, which includes New York’s Gogol Bordello and Balkan Beat Box. Mainstream acts aside, with few exceptions, Balkan Beats is an immigrant phenomenon. It is a sound created in the West, spread by refugees fleeing Balkan wars and driven by nostalgia for their homeland. German-Romanian Frankfurt DJ Shantel likens Balkan Beats to the music created in London and New York in the sixties when a generation of immigrants from the West Indies brought their roots and music to the West to father dancehall and ska. Likewise, Balkan Beats is a sound created in exile with one ear directed at the homeland and the other at Western pop and rock. To understand what the DJs and musicians of Balkan Beats are doing it helps to know where they are coming from musically. Many have come from former Yugoslavia, where they grew up surrounded by the musical phenomenon known as turbo-folk, a pejorative term used to describe, in most instances, a kind of fast-paced, homegrown, folk-rooted popular music widespread in Serbia and Bosnia. Turbo-folk is a hybrid of traditional rural melodies and modern electropop played by Slavs and Gypsies alike and characterized by maniacal keyboards and yowling oriental vocals. It’s a smorgasbord of musical traditions, including popular music of Serbian and Gypsy brass bands, Middle Eastern beats, Turkish and Greek pop music on one side and rock and roll and contemporary electronic dance music on the other. Turbo-folk was derived from contemporary Balkan folk, but uses electronic instruments instead of the traditional accordion. Perhaps turbo-folk can be distinguished from its predecessors by its incorporation of western elements like electric guitar and heavier, dance oriented beats. Also, whereas traditional folk music sang of such innocent subjects as beautiful villages, flowery fields, and unhappy love, turbo-folk took drugs, alcohol, luxury cars, immorality, adultery and revenge as its subject matter and set it to folk melodies, strong beats and synthesizers. The term itself was coined in the late 80s by wacky Montenegrin rocker Rambo Amadeus, who intended to make a satirical commentary on what he saw as a more or less negative musical phenomenon. The child of war-years, turbo-folk was the musical expression of a nationalistic, isolated country, brought to its knees by hyperinflation. It was the soundtrack of Serbia in the 90s: a brash, plastic hybrid sound celebrating the values of Belgrade’s new rich: the criminal elite, the smugglers, the racketeers. The sound became the house style of expensive new venues in New Belgrade like Folkoteka, along with the sound of the trashy new Milosević sponsored television stations like TV Pink and TV Palma. They’d broadcast turbo-folk videos of artists such as Snezana Babic Sneki and Dragana Mirković—the quintessential video filled with gold jewelry, luxury cars and huge new houses, depicting young women in knock-off Versace living it up in the mirrored bars and casinos of Belgrade’s luxury hotels—the Intercontinental, the Hyatt, the Metropolitan. One famous turbo-folk lyric of the time runs: “Coca-Cola, Marlboro, Suzuki/Discotheques, guitars and bouzouki/That’s life, that’s not an ad/Nobody has it better than us.” Turbo Folk singers are generally leggy women dressed in short sequined miniskirts, pushup bras and are caked with heavy makeup. As gangsters took over Belgrade, turbo-folk cozied up to the underworld, becoming the music of choice for the shaven-headed young men known as the “dizelasi,” because of their fondness for Diesel clothes and the fuel smuggling from which they made their money. “Turbo-folk, is the sound of the war and everything that the war brought to this country,” says Petar Popović, director of the country’s state-run record company in 1994. “It represents everything that has happened to this country over the past few years.” It is curious to note that turbo-folk is often objected to as a conveyor or nationalist ideology. The genre was often denigrated by Serbian nationalists as not sufficiently Serb, as a corruption of “pure” Serbian music for its use of oriental rhythms. Turbo-folk, as they saw it, constituted a “Tehranization” of Serbian culture. It’s also worth mentioning that while admired and copied in other Balkan countries, it has its own homegrown Balkan counterparts: chalga in Bulgaria, manele in Romania—all equally controversial and all derided in the media and by western oriented urbanites. For many, a Diaspora of DJs spinning Balkan Beats and turbo-folk is seen as a kind of embarrassment. To aficionados of Balkan music it’s the bane of the Balkans, a musical plague that has spread across the Balkans from Serbia and Bosnia to Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia and even Romania, leveling everything in its path with its cheaply produced synthesizer beats. From the perspective of progressive Balkan urban individuals who have grown up with western rock and roll, the whole turbo-folk attitude is also seen as something repugnant. Its adherents are described as primitive, shaven headed, gold-chain wearing grobians and rednecks, the style an offense against good taste. Mention turbo-folk to any self-respecting Balkan cosmopolitan and watch him wince. The night before meeting with DJ Robert Soko I spent at the Discotheque Hollywood, a Yugo club on Berlin’s Potsdamer Strasse notorious for its punch-ups between Serb and Bosnian patrons, the occasional shooting and knifing. The night I was there I saw the Serbian singer Seka Aleksić, a prime example of the Serbian turbo-folk genre, serenading the mostly Serbian (shaven headed, gold-chain wearing) crowd with wailing folk ballads and turbo-gypsy anthems. I mentioned to Soko that I had seen Seka Aleksić, he cringed. “Yugoslavians are divided between people who love this ‘narodna’ music and people who don’t love this,” said Soko, “and we belong to the second category. We don’t hate it, but it’s just not our scene. We try to represent ethnical music in another way, in fusion with other musical styles, western musical styles. This is, I think, the main difference. I never play this turbo-folk shit.” Soko grew up in Zenica, Bosnia, listening to western music—to rock and roll, to punk, to ska. In his younger years he couldn’t stand ethnic music. They called it narodna music in Yugoslavia, national music, or folk music. It was running on every radio station in Bosnia and most of the young people in Soko’s circle felt bothered by it, hassled by it. It was the dominant music of the former Yugoslavia and it meant nothing to Soko and his friends. In 1990 Soko fled Bosnia and came to Berlin. He took a job as a taxi driver and started hanging out at the Arcanoa, a punk bar in Kreuzberg, with his Yugo friends, mainly, he says, because they were all hashish smokers and someone had a connection in the bar. The Arcanoa became their domicile. “It was a shelter from this turbo-folk shit,” says Soko. “We discovered a place where you could be Muslim or Bosnian Catholic or Serb, where nationality didn’t play a role. And by this time nationality was a very hot issue. Being a Serb or being a Croat was very important. But it wasn’t for me, and it wasn’t for many others. And in this place we could identify with nothing.” After a while, Soko came up with the idea of asking the proprietress of the Arcanoa if he could play some of his Yugoslavian music. The proprietress agreed out of sympathy for the refugees, and Soko started playing his Yugo music. They got free beer and fifty Deutschmarks a gig. All Soko had were tapes at the time: Yugo rock, new wave, punk, ska, the music he had grown up with. They celebrated socialist holidays: Tito’s birthday, Day of Women, May First. The parties were a mix of irony and nostalgia, and Soko was surprised at how many people came to the parties, for nostalgia for Yugoslav socialism was not the “in thing” in those days of growing Balkan nationalism. And yet the parties grew. “Gradually I began to realize that there were many of us who liked the idea of not belonging to a nationalistic group,” says Soko, “to be nothing, to be a Berliner.” And yet, after living in Berlin for a while, Soko found himself eventually returning to his ethnic Balkan music roots, the roots he had rejected as a youth in Bosnia rebelling against the turbo-folk mainstream. This was largely thanks to two figures, Goran Bregović and Emir Kusturica, Bregović who revamped Balkan gypsy melodies, making Balkan music palatable for a western audiences, and Kustrica, whose Gypsy-inspired films Bregović did the soundtracks for. Soko and his friends loved what Bregović was doing, reinterpreting the Balkan music that had been around Soko and his generation, but that they had chosen not to acknowledge. They now loved it and identified with it. They saw their own heritage reflected in the music and realized that something important was going on here, that folk music, if presented in the right way, was actually quite appealing. Suddenly, after having his ears tuned for so long to the West, Soko realized that his own musical roots had an undeniable value. And so, Soko started to play Bregović’s Gyspy beats during his Balkan music nights at the Arcanoa and later at the Mudd Club in Berlin, Mitte. The music was a hit on the dance floor; Soko saw that women especially were drawn to this gypsy brass music, and if the women danced to it, then so did the men. They played more of this gypsy brass, mixed together with western electronic elements, Jewish klezmer, Turkish pop, and the occasional Yugo new wave anthem. People got drunk and went crazy. Germans started to come to the parties, attracted by the wild gypsy tunes and the exotic, romantic Balkan atmosphere. A scene developed. Gradually Soko dropped the socialist holidays; the punk, the rock and the ska fell more into the background. Balkan Beats was born. Soko took his DJ gigs to other cities—Paris, New York, LA. He compiled a couple of CDs, and now he’s working on a movie: Balkan Beats: a Musical Journey. “All this started out just as a small party for refugees in Berlin,” said Soko. “Nowdays I see that there are ever more Balkan Beats parties all around the world, not only in Europe. And it just so happens that I was the one who, let’s say, invented the term Balkan Beats. Maybe someone started to work with that before. I don’t know. We started to work with Balkan Beats. People loved it, identified with it. I don’t know what will happen next. I just see that the interest is growing and we have become kind of a label, like salsa for example. Now Balkan Beats had become a script or something. More and more people are accepting it and saying, ‘Oh, yes, it’s Balkan Beats.’ It just happened by accident, actually.” The Balkan Gypsies Central to Balkan Beats is the music of Balkan Gypsies. A music that has been around for centuries, it is a kind of Balkan communal property. Played at weddings, funerals, circumcisions, baptisms on the streets and in public places, it is a music interwoven in the Balkan social fabric and popular psyche; it is an expression of the Balkan soul and a music played from it by a people who, after centuries of transmigrations, blended together musical styles from East and West. It is a music that streams from instruments left behind by the Byzantine liturgy and Ottoman and Habsburg marching bands, a music that up until now has not been a part of western pop culture, leaving it to Bregović and the DJs and musicians of Balkan Beats to move it towards a kind of global pop credibility, for better or for worse. The Gypsies have always played the role of mediator between different cultures. In Serbia and Macedonia, the Gypsies are very significant for their musical life, and are an obligatory part of every celebration. Their music contains a large number of oriental elements. In 2005, British music critic Garth Cartwright came out with a book about his journeys among the Gypsy musicians entitled "Princes Amongst Men." Writing for the gucafestival.com web page, he described how in Serbia, the Gypsies absorbed the Balkan brass band tradition—brass orchestras being first introduced to the Balkans by the Turkish military who had them marching in front of the troops in order to intimidate the enemy. “The initial form was provided by Austrian court influence at the beginning of the 19th century,” Cartwright writes. “The Ottoman Army belatedly followed, forming its own brass ensembles: mehter. The Janissary army dissolved the mehters in 1839, so leading to large ensembles fragmenting into smaller configurations called orkestars. These transferred their service to local patrons, traveling to play for outdoor gatherings (weddings, funerals, circumcisions and sobors: picnics held on Saints days). The Roma, always highly regarded by the Ottomans for their prowess on wind and string instruments, would surely have been in brass bands from the beginning... The orkestars proved popular across southern Serbia, eastern and Aegean (now northern Greece) Macedonia, west Bulgaria. Serbia remains the brass powerhouse.” In his book, Cartwright describes the music of Boban Marković as “Music of spirit, of flight, stuff that goes way back, pre-Roma, pre-Slav, back to the Celt’s mournful melodies which stayed alive through shepherd and village song, music which travelled across Asia with Boban’s ancestors, mysterious music which absorbs all and builds something new yet still has strong ties with its ancient roots.” A musician of my acquaintance, when he heard Boban Marković for the first time, did not associate him with Balkan Gypsy music at all but rather with Mexican music—mariachi. And this is no coincidence. There is a strong similarity between Mexican mariachi music and Gypsy Balkan brass that is not purely accidental. Just as Habsburg armies were the first to bring brass music to the Balkans, so they were also the first to bring brass music to Mexico. Thus brass music on both continents developed along similar lines. And this is not merely the case in Mexico and the Balkans, but also in Brazil, Africa and India where colonialism brought with military and church brass bands which were adopted by the locals. European military and church bands became the world’s top global music exporters. Locals throughout Asia, Africa and the Americas were trained in the ways of the marching band. Official bands became village bands and by the turn of the 20th century most of the world shared an ingrained knowledge of things brass. All brass bands thus have a link somewhere; they're all based on the same elements. The brass music in Serbia that Gypsies are the masters of—trubace, from truba, meaning trumpet—is no passive entertainment. Serbs don’t simply watch Gypsies play, as you would sit in front of the television and watch a football match. They get into the activity themselves—dancing, prostrating themselves before the musicians, embracing them, not to mention plastering the musicians and their instruments with money, or baksheesh. Serbs hold a widespread feeling that the Gypsies express the Serbian soul through their music. Indeed, with large quantities of alcohol, the Serbs experience a form of transcendence. Thus Gypsies are welcome in any occasion, from weddings to funerals to christenings. The Guča Festival For the most vivid expression of this kind of near-mystical involvement in brass music, it is sufficient to go to the Guča festival. At the end of every August the central Serbian town of Guča, with only 2,500 inhabitants, attracts a quarter of a million Serbs for three days. They come to see bands from across Serbia play and compete for prizes for the best trumpet player, best brass band and so forth. It’s an occasion of wild abandon and has been described as the Woodstock of brass music. Imagine, if you will, a kind of Notting Hill carnival—streets crowded with rides, booths, makeshift restaurants, tents, stalls selling everything from traditional Serbian arts and crafts, Serbian folk costumes, Serbian trubace and turbo-folk music, farm appliances, Chetnik hats and T-shirts with the visages of indicted war criminals on them. Test your strength booths, punching balls, grilled corn, ćevapčići, roast suckling, cotton candy and music coming at you from every direction, dozens and dozens of Serbian and Gypsy brass bands marching in formation down streets, playing for baksheesh in restaurants, competing with other bands for the attention of patrons. Everywhere awnings are rolled out and instant restaurants are created. Here orkestars enter, surround a table and blast. If the table's occupiers want music they start pasting some Serbian paper currency—dinars—on musicians foreheads and trumpets and the sound accelerates. When the table’s attention drifts, the orkestars move on. Describing Guča, the musician and Balkan Beats DJ Shantel says, “Guča is a chaos. It’s an anarchic situation where there is a lot of alcohol, a lot of food, and I’m not talking about simply dishes. I’m talking about whole cows on a grill. It’s something very primitive, but in a positive way. And it’s about nationalism. For most Serbian people, it's a very nationalist happening; for the hardcore left-wing just as well as for the hardcore right-wing. And it’s also very sexual. So you have for three days an area which is out of law and out of control, and there are fights and brawls.” This is entirely true. Having said this, though, the atmosphere is not at all ominous or threatening. The people are extremely friendly and effusive, as a foreigner you are embraced at Guča, for the Serbs regard Guča as the best of Serbian culture, the real face of Serbia—and they are happy to share it with strangers. The real paradox of Guča, as I see it, is the extreme nationalist sentiment that it attracts, and as the writer Garth Cartwright points out, “That the pure products of Serbia go crazy, buzzing on nationalist myths to the sound of gypsy musicians, true internationalists, makes for some paradox.” But then everything about Guča defies rationalism. It might also be interesting to mention something about the development of Guča, how such a big, crazy folk festival came about actually. The festival started in the 60s. At the time, everything folkloric was big in Tito’s Yugoslavia, and some Communist apparatchik had the idea to start up this festival as a way of promoting local brass bands, as the tradition of the brass band was then on the wane somewhat. Gradually the festival became national in scale. Bands came from across Serbia to play and compete. And then in the 90s the festival really took off owing to the increased popularity of brass music among Serbian youth. Inspired by the movies of Emir Kusturica and Goran Bregović, trubace music became the party music of choice for young Serbs, supplanting rave and hip hop. Today the festival has become somewhat commercialized, and it has taken on something of an international dimension with bands coming from abroad as well. I went there last summer, and despite what people say about Guča not being like what it was in the past, I have seen nothing comparable. The sheer level of emotion surrounding the music is like nothing that you could experience in the West. It is amazing to see Serbs identifying so completely with their music. The sheer abandon is something to behold. As I said, there is this feeling here that this trubace music expresses the deep Serbian soul. And you don’t have to be Serbian to enjoy the music. As Garth Cartwright says, “At the dawn of the twenty first century no other music on the planet kicks quite so hard, offers so much primal funk, as a Gypsy brass band.” The rise of Guča is part of an interesting development in Serbian, in Yugoslavian, and I would venture to say in Balkan society as a whole. What accounts for this rise in popularity in ethnic music in the Balkans? Take a look at Germany, for example: ethnic music—the Bavarian brass band—has been on a steady decline since the end of the Second World War, and no renaissance is in sight. Even in the Czech Republic, a country where I lived for five years, traditional brass music is seen as something decidedly uncool. The same can be said for most of Europe, with perhaps the exception being Italy, where several DJs appear to be rediscovering ethnic Italian melodies. But nothing in Europe, at least in the west, can compare to the renaissance of ethnic music in the Balkans. And what accounts for this? It is still something of a mystery to me and it is a question I have put to nearly all the musicians and DJs I have interviewed in my research of Balkan Beats. The Yugoslav War One factor clearly is the war. If you can imagine, up until the time of the Yugoslavian wars, the youth of Yugoslavia listened predominantly to western derived rock. Punk was very popular. The Yugoslavian New Wave scene was very rich. The most popular band in Yugoslavia’s history was a rock band called Bjelo Dugme (White Button), who’s sound was unquestionably western and not at all Balkan. Suddenly the war comes. Serbia finds itself isolated from the West with an embargo is imposed on the country. Eastern Europe’s most westward looking and liberal country, Yugoslavia, suddenly finds itself with the status of pariah state. This must have repercussions with regards to music. And in fact it comes as no surprise that, cut off from the West, people should return to traditional folk music for entertainment. This return to the roots took two forms in Serbia. On one hand, it resulted in turbo folk—folk melodies, but injected with western rave and dance floor elements. On the other hand a renaissance in trubace music, Serbian brass music developed. Clearly trubace music has a strong nationalist component. Many of the most popular trubace melodies are military marches, or at least songs and melodies with strong nationalist overtones, so it should come as no surprise that in this sense trubace music should, during the Milosevic era, suddenly find increased popularity. What is surprising is that trubace music becomes not only the music of choice of the conservative nationalists, but also the young, hip, urban kids. And there is no doubt that this was and is the case in Serbia. Two figures contributed to this pop culture development: the filmmaker Emir Kusturica and the musician Goran Bregović, Kusturica through his movies Time of the Gypsies, Underground and Black Cat White Cat, and Goran Bregović through the soundtracks he composed for these films, using melodies from such Gypsy artists as Šaban Bajramović and songs from the Boban Marković orchestra. Such movies quickly assumed cult status in the West and with it the music, and therefore young, hip, western oriented Serbian youth also came to see these things as hip. Suddenly they saw their own culture, which they may have not up until then considered as cool, approved of in the West, and suddenly it is given a new credibility and becomes “hip” for them. I would like to posit a second thesis as to why trubace music suddenly became popular with Serbian hipsters, and that is that it is largely the creation of Serbian Gypsies who have long had an outsider or rebel status in Serbian society. But more than that they express a kind of fatalistic view of life, as the Serbian DJ Ivan Redi explained to me—a view of “life lived on the edge,” and a belief that life must be lived for the moment. Many Serbs admire the Gypsies for their free spirited lifestyle, and it is my belief that the current renaissance in Serbian trubace music in large part grows out of this admiration and wistful identification with the Gypsy way of life. But it’s important to point out trubace music and turbo-folk are not Balkan Beats. Balkan Beats is something else entirely. Balkan Beats did not grow up in the Balkans. It has its roots in the Balkans, but it evolved in western capitals where immigrants from the Balkans came fleeing war or seeking a better life. Some of these Balkan refugees and immigrants, out of nostalgia for their home countries, gathered together in locales where they played their national music whether it was the narodna music of Serbia or the sevdah of Bosnia, or in the case of Robert Soko and his friends, Yugo rock and new wave hits from the eighties, punk and ska. These were largely insider gatherings attracting only disapora Yugos, but occasionally Germans or other Europeans came too, and they got turned on to a new culture. Thus Yugo DJs began catering to an audience that was not only made up of Yugo refugees but Germans or Frenchmen who were attracted to the romance, the anarchy, the exoticism of the Balkans. Added to this, many of these DJs had their ears attuned not only to the music of their Balkan homelands but the music of the countries they were presently living in and music of other non-European cultures as well, such as Turkey or north Africa, which they worked into their mixes and remixes. And so something new was created, a new sound that was half Balkan half Western. A further development occurred when German and European DJs themselves started mixing and remixing the Balkan sound. Out of this developed a Balkan style refracted through a western lens, created by people who maybe saw in Balkan music something that was missed by the people from the Balkans themselves. This is, for lack of another term, Balkan Beats. There are a number of elements to this Balkan hybrid sound. At the forefront there is the gypsy brass element, there are the various Serbian, Bosnian, Macedonian, Bulgarian, Romanian ethnic and folk elements, the traditional dances—čočeks and kolos— in the case of Robert Soko there is a nostalgia-tinted Yugoslav new wave element. There is a Turkish element. There are stray hip hop beats, elements of house, dub and reggae, rai, bhangra and Bollywood, in fact everything that is current on western dancefloors finds its way into Balkan Beats to some degree. All this comes together on the dancefloor to create an audible picture of the Balkans in all its anarchy and heterogenity. Styles collide and blend into each other; sounds that one would never believe could coexist are thrown together in a hot Balkan broth. While speaking to me in an interview, DJ Shantel described his conception of the Balkans thus: “Balkan is for me a symbol of a bastard, of a cocktail. It’s not a clear structure. Balkan was always a kind of boiling, sharp paprika, not controllable, not correct thing. It’s very organic, but very difficult to control.” This is a perfect description of the sound of Balkan Beats. Balkan Beats offers a refreshing breath of fresh air on western dancefloors. It brings to the dancefloor an archaic folk culture, full of ritual and ceremony, things one would normally regard as out of place in urban night clubs where clubbers usually pride themselves on their cool, aloof, ironic stance. Balkan Beats is not cool. Balkan Beats is hot. It offers passion instead of irony and in this sense it may be a timely antidote for an overly self-reflexive club culture. Meanwhile, In New York Recently I was speaking with Ori Kaplan, the saxophonist from the New York Balkan Beats outfit Balkan Beat Box. He told me a little bit about the Balkan Beats scene in New York, which from his description seems to have taken on a completely new dimension than in Europe. He sees in Balkan Beats in New York a movement reminiscent of the early days of punk or hip-hop. “America is looking for its roots,” he explained. Jews, Bulgarians, Russians, Serbs are looking back to their musical heritage for something that is missing in our cool and nihilistic contemporary pop culture. Ori Kaplan describes Balkan Beat Box’s style of music as “New Mediterranean” growing out of the musical melting pot of Israel where he grew up and New York where he immigrated to. Ori Kaplan, who grew up in Jaffa, Israel, where he watched Egyptian orchestras on television and learned to play Eastern European klezmer clarinet from a Bulgarian trained by Gypsy brass musicians, and got his musical start playing in industrial punk bands. That all changed when he heard a CD from Kocani Orkestar, Macedonia’s top gypsy brass band, and learned about the Gypsy-Turkish fusions of the Bulgarian born maestro Yuri Yunakov. “I started to listen to Balkan music constantly,” says Kaplan, “I became a brass band freak.” The Balkan flavor is palpable in most of Balkan Beat Box’s tracks, which mix Balkan brass together with klezmer and north African rai. Balkan Beat Box describes its mission as about “finding the middle ground between the mechanical and the soul, between electronic and hard-core authentic folk music.” It’s about opposites that produce the daring influence “not just Balkan music but also Mediterranean, southern rim, north African.” Their parties have been a great success in Europe and in America, where they’ve attracted people from the Latino and hip-hop scenes as well. “People want to get away from the cold and cynical electronic vibe,” explains Kaplan. “They want something vodka drenched, sexy, where it feels like you are dancing at someone’s wedding. There is a need for that in America as well as in Europe.” “Balkan music means joy and madness,” says Kaplan. “This is a kind of music that couldn’t have been achieved in the West. It’s a music that is created with bare hands. Such raw emotion is not possible in the West, this complete abundance. People are tired of corporate friendly rock and roll. They are hungry for the really sweaty, personal, alcohol driven, familiar, ceremony-like music.” “In New York,” Kaplan continues, “Tamir [Kaplan’s partner and Balkan Beat Box’s number two] and I feel like we’re part of a movement that’s very spirited and has a lot of energy. It’s an immigrant underground music and party scene where people are sick of this American corporate global music that’s being pumped wherever you go. People are looking for something creative and authentic in its own way something that’s not touched by the corporate must-sell approach. There’s something very healthy about all this interest in brass music. People just want to get back in touch with their feelings.” The Bulgarian born New York DJ Joro Boro is someone else in the New York Balkan Beats scene who sees a counter cultural element in Balkan Beats. Boro, who is the house DJ in Manhattan’s Bulgarian Mehanata Bar where he mixes Balkan Beats with Indian bhangra beats, Algerian rai tunes, flamenico hip hop, Brazilian favela funk, says, "the way I see it, playing this mix is a counter-cultural move in reaction to the hegemony of western pop that can be heard in translated versions all over the world. When you reverse the polarity of this one-directional flow of cultural values, you get a polyphony of styles, musics, lifestyles, and that’s a political gesture going beyond and even against the current popular trends.” The Bukovina Club The Frankfurt DJ Shantel is another example of a musician and DJ who blends Balkan sounds with electronic beats. For several years now he’s been touring with what he calls his Bukovina Club, mixing Balkan gypsy brass with Western dance-floor elements. Shantel is the nom de plume of Stefan Hantel, a German Jew whose parents grew up in the Bukovina in north eastern Romania. After the fall of the Berlin Wall he became interested in his ancestral homeland and organized a trip back home to discover his roots. The trip was above all a musical journey. He met with musicians, made recordings, and soon after his return began developing a hybrid sound that blended the archaic music of the Bukovina with elements of Western pop culture familiar to him through his electronic background. The result was Bukovina Club. According Shantel, Bukovina Club arrived at a time when people in Europe were growing bored with the current pop and dance culture. During the late 90s, lounge music was in the ascendant, techno went mainstream, and electronic music went in so many different directions people no longer knew what was what anymore. All of a sudden, with these Eastern European sounds arrived a music with immediate emotion, a music that comes from the body, a dynamic music with a great deal of stylistic variety and variety of mood, ranging from slow ballads to fast paced brass stampedes. “The music itself was, for kids, great party music,” says Shantel. “And the party is alive. It’s boiling. It’s really an explosion. And it has, from its different elements, the character of a rebel music. It’s a music that’s not acceptable. And it’s difficult. It’s difficult to create a marketing concept for this, for Balkan music, because when you come to the pure, sharp sound it’s very difficult to compromise here. For most of these songs it’s no compromise music. It’s very radical sometimes.” Shantel is adamant that Balkan music shouldn’t be pigeon-holed as World Music. Nor should it be seen as folklore. “Have a look at funk or soul or hip hop, whatever, blues, it’s roots music; music which came from little communities in Africa, the slaves of the States or in Brazil. The popular Brazilian music, the roots are in Africa, Angola. But this kind of music is very well connected with the music industry. Nobody will say, oh, it’s folklore. But we here, we still have this complex in that the moment something comes from the roots direction, like Balkan music, most people still take it as a kind of world music, and for me, in my experience, it’s part of pop culture. If it isn’t already a part of pop culture then it will be.” The danger, of course, to Balkan music becoming part of pop culture is that it becomes watered down and reduced to its lowest common denominator, as when the British group Basement Jaxx makes use of Balkan brass on its latest album. Balkan music becomes integrated in mass production and mass commerce. Like mass produced goods, folk music destined for global consumption is prone to lose nearly all of its original features. It is influenced, directly or indirectly, by fashions and trends, which determine its saleability. It becomes superficalized. So far, though, Balkan Beats exists in a gray zone between underground and mainstream. The Vienna DJ Dunkelbunt is a north German native who first got turned on to Balkan Beats upon arriving in Vienna and hearing Boban Marković on the radio. A veteran of the electronic and drum and bass scene, he started frequenting Balkan parties in Vienna and eventually started incorporating gypsy brass in his own line-ups and club remixes. He is not so much interested in Balkan music per say, but rather insofar as it serves as a bridge between the music of the West and the music of the Orient. “Many people who are directly confronted with the Balkans will gradually be weaned in the direction of something through this music,” says Dunkelbunt. “There is a kind of symbiosis here. Through Balkan music people will eventually realize how cool some of this very foreign stuff is. I think that’s the key for me concerning Balkan music. Balkan music is the link between East and West. You can connect to the Orient through Balkan music. Balkan music is the bridge. That is what is so special about not just the music but the region, and of course the music is an expression of the region. The Balkans is a place where the West is confronted by the East.” According to Dunkelbunt, Balkan Beats is the crucial part of the world music puzzle that makes it possible for western European youth to get into Turkish, Arabic, and Bhangra music. Up until now, that piece of the puzzle was missing in the European club scene. As a result, European clubbers found it hard to embrace Eastern music that was stylistically very different from the music of the West. “There was this Indian music that was trendy for a while. Asian Dub Foundation, Panjabi MC and the like in London. Asian Beat,” says Dunkelbunt. “For some reason this stuff didn’t really catch on. It started getting popular in the mid nineties and then it suddenly stopped. And now I think it’s getting a second chance through Balkan music. Now it’s coming through this Balkan harmony: the Indian stuff, the Anatolian stuff, the Turkish things, the Arabic things. The bridge is now present. Now people can move on to other things. But without the Balkan bridge it was always like, no, it’s too much, it’s too different. Now we’ve laid the foundation and we can build from there. I’m very excited to see what comes next.” Back to Serbia and Kosovo As I mentioned, Balkan Beats remains a western dance-floor phenomenon. Curiously, it has found few echoes in the Balkans itself. Recently I went back to Serbia and Kosovo and asked around to find out whether there were any DJs mixing European electronic music with Balkan ethnic sounds and my questions met with little response. I heard about a rock band from Pristina that incorporated ethnic motifs in its music and a jazz group from Macedonia that brought in folk elements, but it appears there are no figures like Dunkelbunt, Shantel or Robert Soko working in the Balkans today. Either musicians or DJs are firmly in the folk and turbo folk camp or they are firmly in the western European electric camp. There is almost nothing in between in the Balkans today. The one exception I found was the Belgrade DJ and musican Milan Stanković, otherwise known as Sevdah Baby. Sevdah referes to a typical Bosnian style of love song, very oriental in spirit, denoted by its Turkish name, which means yearning, love-sickness, or a melancholy longing. It is melancholic music making use of a wailing oriental vocal style and accordion playing. Milan Stanković draws reference to sevdah not so much as a musical style but rather as a state of being, a kind of painful/pleasurable lovesickness, blending the emotion of sevdah music and some of its folk melodies with house and electronic music. Meeting with Stanković last April in Belgrade, Stanković explained to me, “The first reason why I started mixing these samples of folk music into house and other forms of electronic music was that I found it rather amusing. It was grotesque and a bit ironic for the “cool” and “fancy” clubbing population, and yet so mind-blowing for straight folk music lovers that I couldn’t resist doing it. It is always interesting for me to hear my tune, “Los Ritmos Balkanos” in a club in some house DJ set. People are always confused when the folk sample comes up. They don’t know if they will still be cool or urbane if they continue dancing. But their body says yes.” A controversial issue remains. Many DJs from the Balkan Beats camp sample traditional Gypsy tunes in their remixes without giving overt credit to Gypsy artists. Garth Cartwright has drawn parallels between black blues musicians in the American South, who had their songs appropriated by white rock and roll musicians in the 50s without them receiving royalties. Gypsy musicians from the Balkans today are seeing their traditional songs recycled by non-Gypsy musicians and DJs into modern remixes with drum machines and overdubbed horns for western consumption without them receiving due credit. The primary culprit as Cartwright sees it is the Bosnian musician Goran Bregović, whom he calls a “master thief.” Among Gypsies, Bregović’s techniques of musical appropriation are looked upon with some ambivalence. While recognizing that Bregović has taken something which was not his and put his name to it, many Gypsy musicians nevertheless respect Bregović as a musician who has popularized a style of music that, without his involvement, may not have become as popular as it is today. Still, Bregović comes out as the chief villain in Cartwright’s book. Cartwright has also extended his criticism to the likes of Shantel. Shantel, for his part, calls Cartwright?s arguments “bullshit.” “You have to know that the musical repretoire from this area is so mixed-up that I think, from the artistic point of view, you can do something like this,” says Shantel. “You can chose a melody and you can make something new out of it, and you can say it’s your own composition. Everyone is taking melodies and stealing. It’s part of the deal. It’s Balkan.” Will the Gypsies ever benefit from Balkan Beats? Many Gypsy musicians have criticized the low musical quality, as they see it, of electronic remixes of Gypsy songs. Nevertheless DJs like Robert Soko and Shantel may prove to be a boon to traditional Gypsy musicians working in the Balkans today. While gypsy brass has had a strong tradition in the past in the Balkans, it has lately become supplanted by cheaply produced synthesizer music. This kind of Serbian turbo-folk, Bulgarian chalga, Romanian manele has yet to find an audience among western clubbers. Gypsy brass, as it finds itself presented by Robert Soko and remixed by Shantel, by contrast, is proving to be a hit on western dance-floors. Therefore young gypsy musicians back in Romania, Bulgaria, Macedonia and Serbia may be encouraged through the success of Balkan Beats in the West to stick to their traditional musical heritage. “The success of this sound in Western Europe,” says Shantel, “for sure it’s a logical motivation for young musicians to do the same just to survive.”

01.01.2008

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment