| Umělec magazine 2003/3 >> POWER TO THE ARTIST (interview with Sislej Xhafa) | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

POWER TO THE ARTIST (interview with Sislej Xhafa)Umělec magazine 2003/301.03.2003 Sezgin Boynik | focus | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

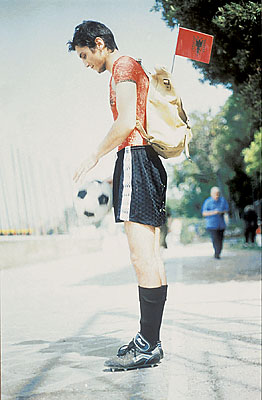

"Sislej Xhafa, an Albanian from Kosovo, travels widely, experiencing various world cultures firsthand, and from this basis he makes his work, touching on illegality, immigration, and authority. He first became known at the 1997 Venice Biennale for his performance Unofficial Albanian Pavilion in which he strolled through the various national pavilions bouncing a soccer ball and blaring a recording of a match between Portugal and Italy, drawing attention to the fact that many countries had no pavilion of their own. Other works focused on tourism, such as Elegant Sick Bus (2001) in Sultanahmet Square, Istanbul’s major tourist site. Xhafa had 25 rural laborers push a mirror-clad bus around the square. He now lives in New York City.

Here he speaks openly with Kosovo sociologist about clandestiness, violence, nomads and the power of the artist. Sezgin Boynik: In many of your works you deal with issues of the underground and the clandestine in the modern world. Do you think clandestiness can change anything in the social sphere? Clandestiness is the future, or even tomorrow. We have a lot of laws that we usually don’t agree with. So in order to survive, we use other ways that aren’t legal. It has become ridiculous, criminal, but we have to learn other ways of living, and use illegality as a way of living with other people, to become better. Listen, let me give you an example. Pick Pocket is a performance I think very much of. Here I use the term criminality to highlight the problem of beauty, of how a poor man can steal from another poor man. Because in this action I steal from a poor Moroccan. I did this in Florence. When you come to Florence you steal something from Florence. That’s a market economy. When you pay 10 dollars for a cappuccino, they’re stealing from you in another way. Today geographical relations bring a field of activity of new attitudes. The arrival of the Kurdish, Iranians use different ways of the old phenomena of migration. These people bring to society more powerful attitudes than the authorities. Authorities can’t stop them. Something more real? More real and stronger. So with the development of technology we have to use it to discover all the new worlds, different forms. You say that we can use criminality as a strategy? Exactly. Take for example my police project. In order to convince the police for this project you have to be in a developed, civilized society. Because with this police station work I bring new attitudes to authorities. This attitude has something to do with a new vision, which can show different ways of collaboration without destroying it. The image of the police is used here as a utopia, as irony. This form of illegalizing into a new context became so strange, so unreal. But the form I use is not to exploit the illegals. I don’t say to them do this, do that, like some other contemporary artists. I’m friends with many criminals, and I never propose anything to them. They would laugh at this, you can’t stop criminality in any way. You must understand that criminality can bring a new identity, a new metabolism to society. People must understand that somebody is stealing because he has nothing to eat. But somebody is also stealing because he is a professional. Professional criminals are like professional painters. Would you say that all systems work like criminals? We are criminals. Do you think that criminality can be a much more interesting way of living? You see, we have one system left. Capitalism. No other system. Communism, rubbish, recycling. Nazi fascism, recycling. So now we’ve got only capitalism. Maybe in the future there’ll be a new system. For that reason we must collaborate with capitalism, not destroy it. No throwing stones at McDonalds, no beating police. You must have an idea. When you don’t have an idea, you use violence. I have an idea and I collaborate. But I also bring in a new attitude. Can you make the connection between violence and criminality? Violence is not just killing or raping — it is something else. We have different violences, we have color violence, for example. Edi Rama [Ed.: Mayor of Tirana, who is repainting the city to create a new image for Tirana] has a color dictatorship. Only a country like Albania would allow somebody like the mayor to use his own capacity of creativity and power for somebody from outside, in order to say to them this is beautiful, this is exotic. This is a very convenient way of thinking. And then there’s verbal violence. There’s violence done by the government when they say you must have clothes like this, speak like this, act like this. But criminals, they’re not committing violence. On the contrary, they’re bringing new attitudes. There is also the belief that criminals don’t live in one place. They are always moving. Critics always write that you’re a nomadic artist. Can you make a parallel between nomads and criminals? First I want to say this. Some son-of-a-bitch invented this nomadism, nomadism. It’s in fashion. I don’t know what it is, but I know that 99% of this earth, citizens of earth in their professional life they wake up every morning to face reality. What I’m doing is bringing in the reality of a variety of countries. I don’t want to think about what it’s like in India. They read fucking Charles Dickens, or whatever. But I go to India, live in that society three, four, five years and then I have a concept of the attitude in that society and country as well. For me it’s important to change places. Because my body needs it. It’s like food. Is this gypsy esthetic a beautiful nomadic criminality? I don’t know. Because if I think, then I’ll never do anything. I don’t think, I act. This kind of living can bring a better understanding of different realities. Maybe somebody with big dick, with a very big dick like in Africa, who every morning says to his wife I love you and beats her with his dick. This is a different kind of expression of love. We must understand and accept this difference. In your works done in very different countries you always criticize the social conditions in that country. You don’t want to accept that you are an Albanian artist who must work locally and exotically. You see, I don’t want to say that all my works are site specific. But you must understand that for me the value of the human being is the most important value I believe in. When we understand the value of the human being we respect that value and we are able to make magical action. My work is related to society as a universal. Art is a universal language. The work I did in Turkey pushing the bus. It was an old Mercedes that didn’t work. This work is also a reflection of the reality in India, America, Germany, Italy…all over the world. You bring in the context of society itself. These people with their poor economy see themselves in the mirror of the bus. And they see themselves in misery. It’s the same situation in India, in Thailand, everywhere in the world where tourism is the rule of law. Tourism brings a fake economy that contradicts and opposes countries’ beliefs. When some Italian goes to Thailand, it’s not that he’s interesting in this culture, but wants to fuck teenage girls. That’s tourism. A big disease. The hospitality and big heart of the Turks towards other nations with tourism they’re forced to fake it; they’re forced to accept tourist attitudes. So this forcing is universal. They’re acting against their nature? Of course. You think that in Thailand they want to be fucked by some tourists? No, they are forced to accept it. That’s very painful, sad. But if an artist like me, like him, like you use some other reality, in my case irony, they bring in something very powerful to a special context. I don’t like to make art only locally interesting. I want to make local what is automatically universal. That’s my sensibility for the world itself. In your interview with the magazine Zarez you say that Szeemann’s exhibition is the first and last Balkan exhibition you are participating in. Do you think that these exhibitions are new ways of colonizing this region? Listen, I talked with Szeemann. I said to him: “Do you know this isn’t good, what you’re doing, you are colonizing the Balkans.” He said, “yes.” Do you know this exhibition is nationalism? He said, “yes I do.” So this kind of taking blame, the way of mea culpa seems agreeable to me. And for that reason I decided to participate in the exhibition. But René Block, no way, I said it to his face. This is a very nice idea, what you are highlighting about the Balkans, very interesting. I’m not judging the concept. But not me. End. End of the Balkans. Because for me the Balkans is looking from a Western position, looking objectively seems wrong. I wouldn’t like the Balkans to become the West. I wouldn’t like the Balkans to become an object. The Balkans have a certain value. People from this territory have a certain value. Maybe they are better than American or Japanese values. What is this value? It’s the personal experience of the personal background of where you came from. I have a certain value that I can’t explain to you. Why explain everything objectively because I’m from one territory. Art is universal. I said to René Block, please go into Kosovo and search for new artists. That’s very good for the future of Kosovo and for the all young ones who don’t have a chance. They have great energy, great potential. But me? No, please. Not me. What do you think about the Irwin project East Art Map. They want to make an art catalogue from inside Eastern European... Can I suggest something better than Irwin’s “New Moment” ... Let’s have something to drink. [Sislej Xhafa’s dad brings in some orange juice] Listen, I’ll respond to this special question. I’ll tell you something, but this is a personal point of view. ....This a is a new moment. Cheers! [laughing, they drink] I will explain very straight with no bla-bla-bla bubbles. I don’t like this project. I like Irwin’s position; they’re great artists. But this new attitude of bringing artists together is very naive. And destructive. I believe in new attitudes of collaboration with Western values. That can bring the East to a better position than “New Moment.” “New Moment” to me is an old moment. But this is my personal point of view, and, again, I respect Irwin as artists. For me, to make something better, we have to find new attitudes of design, new attitudes of presentation, and new strength. Then we can show the values of the territory. But not through one publication, bringing in people like sheep or cows into one cooperative. Like a factory, not good. Maybe we can do something else. We could have one big balloon. And in the balloon all the Balkan artists moving and shouting, Irwin, Christo ... all the fucking artists in the book flying. That is a new attitude of presentation on mobility, what this region of migrations has been living on for centuries. This presentation could be so powerful that it might make something magical. But now it looks like curators are becoming stronger than artists. This is a problem of the artists. I don’t care about them. They invited me to one exhibition in Villa Medici. They wanted to change my project, and I refused to do it. What was it? I came to Villa Medici and they showed me the grand salon where Napoleon, Louis XVI spent their time. At first I said OK. But they have this very, very nice garden there. I wanted to collaborate with the gardeners. To give them my budget of 4,000 dollars to them to buy cigarettes and some extra sandwiches. And everybody will have one big bag. After they consumed their cigarettes, while working, they were to put their butts in the bag. My project was to collect all their rubbish and before the opening make a garden of my own in the grand salon with the garbage. [Laughing] But the curators said, “Oooo, how can we have the grand salon like this!” [Laughing] This project is my power. They didn’t accept it in this way, and so I refused to work with them. I don’t want to fail. If I’d accepted their conditions, I would’ve failed. I’d have lied to myself. So no collaboration. Artists have power. It’s my position, my attitude. No compromise. Forever. "

01.03.2003

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment