| Umělec magazine 2005/3 >> Constructed Decay | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Constructed DecayUmělec magazine 2005/301.03.2005 Henrikke Nielsen | interview | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

Danish artist Simon Dybbroe Müller’s work is founded on a conceptual approach from which an extensive web of art historical, literary and architectural associations is spun. The notions of chance, accidents and decay are subverted in a wide range of materials and interventions, which reveal a fascination with constructed reality. Based in Frankfurt Simon Dybbroe Müller’s most recent exhibitions include a presentation at Kunst Werke in Berlin, alongside upcoming solo-exhibitions in Neuer Aachener Kunstverein and Künstlerhaus Bremen.

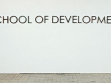

Your presentation Outside Awareness at Kunst Werke includes a big sign saying “School of Development.” I would like to begin by talking about this sign and the material and meaning of it. This piece functions as a kind of headline for the whole presentation and carries the title Speed. It attempted to look like the signs you find on institutional buildings from the late fifties until the beginning of the seventies: iron letters hanging a bit in front of the – usually concrete - wall of the building. It seems as if they are hanging in the air and they are really beautiful. So I have made these letters out of iron and put them in the rain and added a few chemicals so they have begun to rust. “School of Development” leads the thoughts towards an institution or some kind of authority. The fact that the sign is rusting or falling apart, basically, contradicts the word “development” that normally evokes an idea of progress. But development can be anything, and things can also develop backwards. This point has a lot to do with how the rest of the presentation at Kunst Werke works. It can also be related to the wall painting Inside the Wall, Inside of You. Definitely. The wall painting is a superimposing of three existing paintings. One by Max Bill from 1964, one by Paul Richard Lose from 1955 and one by Olla Baertling, who is a Swedish painter, from 1958. The images have been morphed together and where specific colors meet they produce new colors. Then the image has been transferred to the largest wall at Kunst Werke in a sort of constructed decay-situation. It looks as if the layer of white paint is cracking, and it reveals this modernist wall painting that apparently has been there since whenever. It is a kind of perverse entropic situation where things fall apart but it actually makes this underlying scheme or truth visible. On one hand, it looks like a modernist wall painting but on the other, it is almost over the top because it is a bit too crystalline. Through the fact that three paintings have been morphed together it is more complex than these kinds of paintings would normally be, and you find these tiny triangles of color not to be found anywhere else in the painting, which is surprising. You call it “constructed decay,” and such paradoxes play a major role in your work. You also work with apparently random occurrences or accidents, like in the window piece at Kunst Werke. There is this Danish comic character called Strid and in one of the strips, he decides to become a border-breaking artist. He takes a lot of drugs and does a painting with his eyes closed and asks his mate, “Did I make border-breaking art? Did it become really really crazy?” And the other guy says “not really” and Strid opens his eyes and realizes that he has painted Poul Krebs. So he is being very aggressive, but ends up producing the most conservative image he could possibly come up with. Maybe this link is not that obvious, but in the window piece there is also some kind of either decay or violent act towards these windows at play. But every window is broken in the same way, which is screwing up the whole idea of being able to violently break something down. It takes a while before one realizes the “constructedness.” As long as you see only one of the windows you think it is an accident. In another piece, Inside the Ceiling, Inside of You, one discovers a portrait of Le Corbusier, in what at first glance seems to be a damp spot in the ceiling. It is as if you are hijacking chance in your pieces? That is a good word for it. It is also related to the fact that a colonization of that field is already taking place in a broader perspective. In the small catalog accompanying the exhibition, I have written a statement that consists of four small anecdotes. One of them is about how the term vintage has become adapted by fashion. All the denim brands produce vintage jeans that look as if they have been worn by some rock star sliding on his knees on stage for ten years, but they are brand new! And I think that paradox is funny because they decide how the jeans should look like, but they also decide how they should or would look like in ten years! The whole idea of decay becomes a construct. You could also think about the architecture of Site, this American architectural group from the 1980s, who built these ruins that were new ruins. Somehow they project the piece that they make out into the future, which I think is an interesting phenomenon. Your work often focuses on the highlights of modernism, be that within architecture, literature, or visual art. How and why is this period important to you? I think I could come up with 10 different explanations, depending on which mood I am in. One point is that you and I grew up in a society where a certain kind of provincial modernism has had a major influence on how schools are constructed and everything. In Scandinavia, modernism has been such a widespread phenomenon! Furthermore modernism represents – and I guess it is almost a cliché to say – the last period of utopia, and a belief in actually producing truths. All the work that I quote is work that I really like. The artist’s statement mentioned also includes an anecdote about Robert Morris and a show at the Tate Gallery in 1971. It was his first retrospective in Europe, but he decided only to show his old work in a slide show and made these new participatory objects, which were scrappily made playground icons that people could screw around with. The show was closed after five days because people were injured and it reopened a week later as a “normal” minimal art show. What Robert Morris is known for today is his minimal art, right, but he made all these pieces that were about nakedness and about destructive behavior etc. Somehow modernism is like the tip of an iceberg, and underneath it is hiding all this sexual and violent potential! (laughs) It is not unusual for your generation of artists to deal with modernism, but if I compare you to artists like Sam Durant or Simon Starling, for example, one senses a less critical attitude and maybe even a stronger moment of nostalgia in your approach? Maybe my work is not so much about modernism, as it is about “thinking of modernism now.” For example, one might think of the works at Kunst Werke in psychoanalytical terms. What becomes visible when everything falls apart is high modernism. It is about our collective subconsciousness. Something that keeps on haunting us. A lot of the people or projects you are referring to, share a utopian impulse that is impossible to imagine within today’s art practices. However, we are experiencing a longing for the possibility of visioning things differently and of making radical suggestions, maybe as a result of postmodernism’s rejection of any utopian orientation. You are not creating new utopias, but I would claim that your reflections are still part of a longing for the impulses behind utopian thinking. Would you agree with that? To a certain extent. But one could also say it in a simpler way, maybe. If I flip through a magazine and see something that I really like – and say that it is a modernist or minimal art piece - then I would question why I like it. I would see and understand the utopian potential but not be able to take it earnestly anymore because, like you said, it is impossible to think this kind of thought today. So for me it becomes more about how to appropriate this piece and build up a kind of excuse for me liking it. I would need to rewrite it. For example, I did this turned over remake of a Robert Morris sculpture called Box with the Sound of It’s Own Making. It is about how the piece was produced and what it was before it was produced, rather than about the actual thing. It is simply a box and you hear the sound of how it was made. In my case you see a shattered box and a loudspeaker, and it is called Box with the Sound of It’s Own Breaking. What do you mean by “excuse”? Borges once wrote about the fact that he characterised an ancient Japanese writer as “Kafkaesque.” Kafka changed Borges’ look at something that was written a lot earlier, and he saw this Japanese writer through the filter that Kafka had build into history. Maybe this explains what I mean by excuses: if you take these modernists one to one serious, then there is no way you can relate to their work. But you want to like it, and that might be regarded as nostalgic. So at least some of my work is about building up this constructed situation (or filter) where I can allow myself to like these pieces. There is an extensive web of references behind your work, but it is very far from any kind of documentary approach. Could you talk about the relation between the parts that are referential, or the sort of research that your work is based on, and what can be characterised as the more inventive parts of your work? First of all I am not so sure whether I am doing research. I guess I am to a certain extent, but it is very rare that I sit down and research a subject. I read my way through things all the time and then things happen. It might sound like a cliché but that is the way it is. And it might explain why there is no border between my so-called research (if perceived as boring labor) and the part where I am trying to make things work visually and formally. I do like a lot of modernist art, and I do go through a lot of catalogs and I also do listen to a lot of music, so the way that these cross-references occur is very natural to me. Only to mention a couple of things to which I sometimes refer in my work. In that sense there is always something very personal, if not directly autobiographical about your work as well. That is true, but mostly when I build in an obvious autobiographical link, like in the piece I showed at Gallery Kamm called Aarhus Winter 1993, it is very much a decision. These personal references become a tool. I decide that I want it to be autobiographical, and it does not mean that it is not, but sometimes these links are far out and just as fictitious as everything else. For example, the invitation card for my recent exhibition at the project space of gallery Sies+Höke in Düsseldorf was a remake of the book cover of Ufarlige Historier (Harmless Stories) by the Danish author Villy Sřrensen. I simply replaced the name of the author with that of mine. The book was one that I found on my mum’s shelves, and it is important to me that I found it there, and it is important to me that there is an ink stain on it. Also the way the book looks is important. It is a kind of design that I can relate to. There are also stories in the book that relate quite directly, though in a weird way, to the show that I did. One of the stories is called Romeo and Signe, and it is about a girl who can only see when she cries and she falls in love with a glazier. In order to get in contact with him, she breaks the window in her room with her bare fists. Then she lies in bed all bloody and when she wakes up and cries because of the pain, she sees very clearly as the glazier is putting in a new window and talks about how his glass lasts forever. I do not even know if I like the story, but it is formally related to the show, because also at Sies+Höke the gallery window was broken. On a more abstract level, the idea about her only being able to see when she cries has to do with a weird sentimental feeling, that is also present in the show. A way of looking at history is through these crying eyes. Being very sentimental about it makes you capable of seeing things that you would not see otherwise. The show at Sies+Höke also includes a piece called All Yesterdays Parties (Die Wurzel aus Null ist Eins, Kuttner), where you are referring to the painter Manfred Kuttner. How did you come across his paintings? Well, that leads us back to how I “research.” I was interested in doing something about all these artists, that have been forgotten but who were really great, and I ended up engaging in a lot of discussions with people about these kinds of artists. I guess it is a kind of sport for a lot of people to know some artist that is totally unknown. Anyway, I was talking to a good friend of mine and he told me about Kuttner. I wanted to use some artist from the Düsseldorf context, because that is where the show took place, and also because I have been partly studying there myself. During his time at the academy Kuttner was showing together with Richter, Konrad Lueg and Polke. Kuttner’s paintings are abstract, and so are those of another painter you have been referring to in your work, Bernd Ribbeck, however he is from your own generation. Do you have a background in abstract painting yourself? No. Not at all. I mean really not at all! But it is a good point, because Bernd is a really good friend of mine and his work was a kind of window into abstract painting for me. I used to photograph his paintings for him at the art academy and I totally didn’t understand it. But through thinking about his paintings I started to appreciate and understand what this kind of abstract painting was about. I guess another point is that I produce different things with different techniques all the time, which often evolves from a wish to make stuff in which I have no training. Like an amateur! For example, I really like abstract painting, and it is an interesting field to think about now. So how can I make a twist so that I can actually produce a painting, which I have never done before? Now I just did a painting at Kunst Werke; a very big one and it feels good.

01.03.2005

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

|

04.02.2020 10:17

Letošní 50. ročník Art Basel přilákal celkem 93 000 návštěvníků a sběratelů z 80 zemí světa. 290 prémiových galerií představilo umělecká díla od počátku 20. století až po současnost. Hlavní sektor přehlídky, tradičně v prvním patře výstavního prostoru, představil 232 předních galerií z celého světa nabízející umění nejvyšší kvality. Veletrh ukázal vzestupný trend prodeje prostřednictvím galerií jak soukromým sbírkám, tak i institucím. Kromě hlavního veletrhu stály za návštěvu i ty přidružené: Volta, Liste a Photo Basel, k tomu doprovodné programy a výstavy v místních institucích, které kvalitou daleko přesahují hranice města tj. Kunsthalle Basel, Kunstmuseum, Tinguely muzeum nebo Fondation Beyeler.

|

New book by I.M.Jirous in English at our online bookshop.

New book by I.M.Jirous in English at our online bookshop.

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment