| Umělec magazine 2007/2 >> Politics of Friendship | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

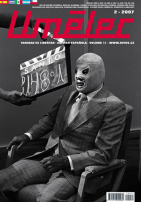

Politics of FriendshipUmělec magazine 2007/201.02.2007 Lenka Vítková | patronage | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

The Politics of Friendship exhibition at the Šternberk Gallery featured five works that focused on interventions into the public space. These works were presented in various forms of documentation. All the works have been represented before and some even together; what is remarkable and noteworthy is the manner of presentation. March 20 – April 4, 2007

When a process leads to an artwork as a conclusion, the artist mustn’t claim innocence. He should acknowledge his own position. -Vasil Artamonov and Alexey Klyuykov. Group exhibitions usually have a common topic that is in some way implied by the curator. In this way, the curator is the one who speaks, and the viewer tries to grasp his or her meaning. Jiří Ptáček, has brought works together in this exhibition that, at first glance appear to have a lot in common. They intervene rather positively within the public space— “a friendly gesture in the public space,” a formulation he borrowed from one of the exhibiting artists, Bára Klímová — referring to the tradition of performance. These were either filmed on video or photographed, and indicate a certain formal moderation, based on their proximity to everyday life. An important part of the exhibition featured the artists’ responses to six questions: 1. What immediate motive brought you to the realization of this event? 2. What - in your opinion – does the person participating in the event or being confronted with the result of it take away from it? 3. How would you define your role in its execution? 4. What meaning do you apply to the record? Do you think it is the goal of your effort or a record of its course? 5 What importance do the categories of “good” and “bad” have for you? Do you consider them seriously or do you keep at a distance from them? 6. Do you think your activity somehow touches upon the question of the function of art? How? The "Účel" (Purpose) exhibition at the AVU Gallery already had featured, in the summer of 2006, a wide range of individual approaches to looking at the relationship between art and real-life situations (Vasil Artamonov, Daniela Baráčková, Petra Herotová, Eva Jiřička, Eva Koťátková, Alexey Klyuykov, Ládví, Václav Magid, Sláva Sobotovičová), with Václav Magid as curator. One of the topics in the exhibition was the phenomenon of ‘purposefulness’ in art – some of the works doing good deeds simply through their sheer existence (paneling made from Fair Trade chocolate bars- Sláva Sobotovičová), others documented the existence of good deeds in everyday life (Václav Magid), and several parodied the very idea of social intervention in art (Vasil Artamonov and Alexey Klyuykov exhibited in Šternberk, too.). While “Účel” connected the similar, the "Politics of Friendship" exhibition worked with the questionnaire to reveal what apparently similar—in details, such that this “phenomenon” or “tendency” gradually crumbles. Works of art are not made any better or worse just because they use public space – such spaces are already overloaded with information, and interventions do not automatically justify their existence. In investigating the differences between the exhibited works something rather unusual becomes apparent: similar results can be derived from entirely different motivation. In this way, the incentives the artists had for undertaking the projects are an important part of what is being shown, and it is useful to inquire into them. Indeed, the performance and its documentation function together as a unit. Peter Rezek’s lectures from 1976 to 1981, published in the book "Tělo, věc a skutečnost v současném umění" (The Body, Thing and Reality in Contemporary Art, 1980), presents the art of that era with a very personal relationship to the viewer. This shows the novelty of teaching perception of art through documentation alone. “More than merely documenting an action, the documentation itself contributes to the sense of the action recorded,” Rezek said. There have been a variety of efforts to “connect to the radical freedoms” (Maja and Reuben Fowkes) of the 1970s. Aspects in common include interventions into civil zones, the ecology of the medium used, and in the moderation of the visuals. But since that era, the technology of documentation has evolved, and emphasis has shifted away from the event itself towards an emphasis on what can be shown in a gallery. Rezek asks, “Is the performing artist protected from what he performs?” Jiřička defined her own role as “caring and nursing,” yet her work is distinguished by perfect choreography. Artamonov and Klyuykov play their usual roles of “artists;” The actions of the Ládví group, which represent themselves as role models, could function as footprints left behind by some invisible benefactor; they simply define their role as “active.” Šedá formulated several tasks to describe her activities in Ponětovice: “1: Mediator; 2: Transferrer; 3: Witness; 4: Friend; 5: Child.” Klímová, in the spirit of “research,”slipped into the skin of artists from one generation before. An important feature of the “Politics of Friendship” was that the exhibition was unusually flexible for understanding, outside the unstated context of contemporary art. Indeed, while the Šternberk gallery is one of the few in Northern Moravia that regularly presents good contemporary art, it cannot be assumed that the local viewers have ever seen anything to compare. As such, this exhibition was accessible, making it possible for the viewers to think about the function of art—and to consider their relationship to their own surroundings as well. The show also had an element of accounting, and, on the whole, was able to generate interesting feedback for the participating artists. The Hardy Boys to the Rescue The Ládví group presented documentation of their activities from 2005 to 2007 around the Ďáblice housing project, in the Prague suburb of Ládví. For the group, the documentation itself is what links their activities with contemporary art—not just to enable the activities’ exhibition. How could we understand their work if we had only heard about it? The documentation’s brilliant photographs show that there is a fantastic photographer among the group’s members; they also illustrate the two operating principles of Ládví: filling in the absent and taking away the unwanted. I will name just a few of these actions. For Osázení obelisku (Mounting an Obelisk), vines were planted around a forgotten peace plaque (a month later, the plants were stolen); Prostříhání keřů (Trimming Bushes) involved trimming bushes to restore the view of a metal relief (Ládví, Ďáblice housing estate, October 2005); Stojan pro 5 kol (A Stand for 5 Bicycles) was a bicycle stand set up at the AVU building (Účel exhibition, AVU Prague, June 2006); Výsadba stromu (Tree Planting) featured the removal of a tree stump and the re-planting of a cherry tree (Prague – Ďáblice, November 2006); Květinová výzdoba za okna (Flower Window Decoration), flowers were placed in the window at the Indikace exhibition (curated by Mariana Serrano Prague, May 2006); e-mail correspondence to remove a poster from a cemetery wall in Ďáblice, Žádost o odstranění poutače (Request to Remove a Poster Prague – Ďáblice, March 2006), resulted in the poster being removed; Krabička s křídami (Chalk Box, Ládví, Ďáblice housing estate, November 2006) featured a box of chalk placed inside a playground; for Zrestaurování pelikánů (Restoration of the Pelicans, Ládví, Ďáblice housing estate, May – September 2006) some pelican sculptures were restored; Oprava vitríny s plánem sídliště (Repairing the Display Board with the Map of the Housing Estate Ládví, Ďáblice housing estate, December 2006) called for the painting of a display case and the replacement of its glass. The group also congratulated their fellow citizens in the monthly magazine for Prague district 8; adopted a girl in India through a long-distance adoption program; and they announced a grant for a ten day study residence in the housing estate of Ďáblice, etc. “We understand the projects in Ládví to be gestures (and not the individual actions in themselves, but the set of actions) that point not only to a group of good-doers, but are also reacting towards and questioning the ‘benefits’ of contemporary art,” the group explains. Their anonymous, and temporarily useful, intervention in these specific urban settings highlights the essence of the locations they confront - they reveal the anonymity of the settings, a deficit of historical memory and the failing functionality of large urban housing projects. When the Hardy Boys Paint a Fence In Natírání plotu (Painting the Fence), from the video series Jak jsme pomáhali (How We Helped, 2006), we watch Artamonov and Klyuykov climbing over a fence in a garden colony, walking along a narrow path until they reach a wooden fence, where they take out cans of green paint and brushes and begin painting over the flaking fence. We can hear the snow squelching under the feet of Vaclav Magid, the cameraman; they seem to be cold, the paint will not dry properly, and we know that they really should remove the old layer first. They paint the fence from only one side, while above them a train goes by, the camera following it. Lights come on in the distance, and, as they are leaving, the chattering of their teeth is audible as we watch them climb back over the fence. Other actions include Okopávání zahrady (Hoeing the Garden), Natírání vrat garáže (Painting a Garage Door), Natírání stromu vápnem (Lime-coating a Tree), and Sázení stromu (Planting a Tree). The artists themselves define such actions as “internally contrasting activities that can be explained as simultaneously caring for and damaging a neighbor’s property. The fifth action shows an intervention into public space.” In carrying out these actions it is important to show for whom they are happening and for whom they are intended. As the artists explain in a questionnaire response, “in the context of contemporary art the project Jak jsme pomáhali... seems like a parody of other attempts to follow socially engaged art, where various socially beneficial activities establish themselves in the everyday business of art—and at closer observation appear to be simply presentations made for the sake of art presentations.” The function of activity As Eva Jiřička moves about in her video Drying Out (2006), the camera remains fixed, Jiřička is dressed in white trousers and a light blue blouse, and starts spreading paper towels of the type used in public toilets upon three cars parked on a calm street. Then she takes the towels, wipes water drops from the hoods of the cars, and then tosses the nearly unused papers onto the sidewalk. She eventually picks them up again and leaves; but, because the video runs in a loop, the drops on the cars reappear, and so the artist continues in her work. “There are two goals for the project,” she explains. “One is to do the action and the other to record the action.” adding that her action “Touches on the actual function of the activity.” Here, rather excessive attention is endowed towards objects (cars) that belong to someone else, and this is enabled by the presence in public space of these objects. This absurd care is defined by a mechanical quality, specialized and rendered with elegant gestures. The construction of normality The action Režim dne (Daily Regime, 2003), was the culmination of a long-term project by Kateřina Šedá called Nic tam není (There is Nothing There), taking place in the South-Moravian village of Ponětovice. The work’s title is a sentence used by the people in the town to characterize it... The artist was motivated by her idea that “village life is like a board game whose repeated course is governed by ‘invisible rules.’” Šedá studied the daily regime of Ponětovice’s inhabitants for several months, and then persuaded most of them to formally recreat it on one day— May 24. 2006. We can see what happened in public space during that day in her video: the street was swept; people went shopping, rode bicycles and sat down with a beer (and behind the camera the artist was surprised that they really did sweep, ride and shop). In addition to this, the citizens of Ponětovice were asked to open their windows at home, get their daily newspaper, eat beef with dumplings and tomato sauce for lunch, and switch off the lights in the evening. As the artist explained, “the meaning of the whole event was to show a normality that can be revealed only through amplification. Only this makes it visible, you must point to it ...” Sitting at a pub in Šedá’s video, one of the citizens of Ponětovice says, “I think normality was when we were young, but today it’s no longer possible on a Saturday at ten a.m. for people to sweep the sidewalk, etc.” The result is the personal experience of the participants who, in ‘performing’ the common everyday activities shown, could feel something special – and at the same time, thanks to digital technology, an idyllic image of communal village life was presented. A construction of anomaly Barbora Klímová is represented by the work Replaced which won the Jindřich Chalupecký Prize in 2006. Five videos capture Klímová’s reprisal of five performances from the ’70s and the beginning of the ’80s. These were: Vladimír Havlík, Pokusná květina (Trial Flower), Olomouc 1981; Jiří Kovanda, Pokus o seznámení (Attempt to Make Friends), Praha 1977; Karel Miler, Buď – a nebo (Either – Or), 1972; Jan Mlčoch, Vzpomínky na P. (Memories of P.), Krakov 1975; Petr Štembera, Spaní na stromě (Sleeping in the Tree), Prague 1975. The accusation of plagiarism, that was issued shortly after Klímová’s winning of the prize, seemed to have not taken into consideration an important part of her video– the soundtrack– which is an edited discussion with the creators of the original performances (with the exception of Petr Štembera). It shows that, while for Klímová the measure for including something, or not, was having the art enter into the urban space through the actual physical intervention of the artist. For the artists interviewed, the most important thing was their own personal experience. This distinction is apparent in nearly all the interviews, and it is significant that Klímová doesn't let this slip away, stating this clearly. “The actions that I chose might be closer to anomalies than they are to any artistic gesture,” explained Klímová. “Sometimes we experience these in the city, and, for me at least, they are a kind of satori.” In this way, she found proximity to the chosen artists mostly from the position of being an accidental viewer. By contrast, Jiří Kovanda explained to Klímová in her video, “the point of view has changed strongly-—at that time people perceived things that weren’t there, the social level rose- it was swelling- and at that time people felt this very personally... to cross the borderline that at the time was unpleasant for me, I wouldn’t cross it voluntarily.” Also in Klímová’s video, the performer Karel Miller said, “We felt that it was necessary to enter the space with our own bodies. My feeling was that the medium was useless, that it was necessary to express oneself without a medium, and immediately. And the second thing is connected with my own nature; I like minimalism, and I started doing things in the most minimal ways I could, not unlike a shaman when he scatters herbs: he rules the whole world for a fleeting moment, and he doesn’t realize his being at that moment—he only thinks about how to do the task well. People distanced themselves. A specific realization was important for us personally – I’m a different person from who I was thirty years ago; I think of myself at that time with emotions... The reality has changed, and, to me, what I was doing back then doesn’t belong in the 21st century at all...”

01.02.2007

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment