| Umělec 2003/3 >> PROVOKE ME, SISLEJ | Просмотр всех номеров | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

PROVOKE ME, SISLEJUmělec 2003/301.03.2003 Petrit Hoxha | focus | en cs |

|||||||||||||

|

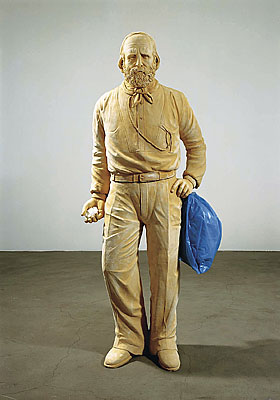

"Horses like sugar, its taste. Making use of the pleasure that this powerful animal takes in sweet things, artist Sislej Xhafa, in the middle of the empty gallery space, placed a 162-centimeter-high terracotta sculpture of the legendary Italian hero Giuseppe Garibaldi with a few crystals of sugar in one hand, and a plastic blue bag full of sugar in the other hand. But the horse — the ubiquitous symbol attached to so many national heroes throughout European squares and avenues — is

missing in Xhafa’s last exhibition, Twice Upon a Time, in Magazzino d’Arte Moderna in Rome. This fact seems to have forced old Garibaldi to set out in search of him. In the neighboring space, horse shit litters the floor, and the pungent smell in the air is evidence of his recent escape. Could it be that the surprising absence of the horse is the artist’s subtle whisper that immigrants (whether they’re Albanians, Kurds or Moroccans) have stolen the hero’s horse from the Italians, nabbing from them a part of their history, and therefore a part of their state? Or maybe aging Garibaldi is trying to tell us that it’s the immigrants who are now going to bring Italy forward… Twice Upon A Time never exchanges words and does not communicate with the broader public like we are accustomed to from Xhafa’s other works, thus limiting the interpretation to one territory, one language. 1. In a red T-shirt, black shorts and long black socks, dressed as an Albanian national soccer player with a little Albanian flag stuck in a backpack that holds a portable radio playing a soccer game, Xhafa, bouncing a soccer ball, scored his first art goal with his intervention The Illegal Albanian Pavilion in the Giardini at the 1997 Venice Biennale. By encouraging Biennale visitors to play with him, the artist very subtly incorporated them into his duplicity, as they unconsciously cooperated with the uninvited Albanian pavilion. Another aspect of Illegal Albanian Pavilion was its movement. Faced with extreme poverty as a consequence of the worst communist regime in Europe, hundreds of thousands of Albanians at the beginning of the 1990s left their homelands for the West. Their movement in search of a better life was reflected in the artist’s reaction, in which the performance itself was in constant motion. In this way he touched non-aggressively on the issue of the non-representation of many poor nations in the biggest and most well-known contemporary art exhibition in the world. Using soccer as a sport, and sports in general as a medium for communication and contact between people, Xhafa made us aware that sports set a good example for the arts. Since the beginning of his career Sislej Xhafa has been dealing with various injustices, encouraging awareness of questions permeate our existence. Here he asks why Luxembourg, with its three-hundred thousand citizens, have its own pavilion in Venice, and poor states like India, Mongolia, Albania, the Sudan and a dozen others are still left on the sidelines… 2. Sweet Invasion (2000), a series of color photographs with triple-plated gold frames installed in a gold-painted room, presented another problem in a similar way. Strange, arrogant-looking men dressed all in black, with sweet and smiling faces, fill the images; their golden chains and rings remind us of ordinary criminals. Here “high-class” gallery/museum visitors are forced to face photographs of a group of criminals; the effect is one of opening the prejudices of a society against “those weird foreigners, who speak an unusual and mysterious language and that, more often than not, take advantage of our system.” People have to learn to question their prejudices, states the artist. In Piazza della Signoria (1999), in the central square of beautiful Florence, where visitors are often easy prey for pickpockets, Xhafa himself became the thief, but instead of annoying tourists, he picked on another immigrant, in this case a poor Moroccan. Here the roles were changed, and the immigrant was suddenly on the same level as the tourist — both the victims. 3. Prejudice and xenophobia, taboos, immigrants and their search of identity, and also the insistence on regarding foreigners as cultural contributors rather than potential criminals are central themes that characterize Xhafa’s (1970) oeuvre. The artist’s constant rebellion against the contradictions of today’s societies, stems, I think, from his childhood in a conservative community in Kosovo under communism, and later from his choice to turn down going to the local University; instead he went to London’s Chelsea College of Art and Design. But Xhafa was disappointed with the English university, and after falling in love with an Italian girl he decided to move to Italy, where he began attending Florence’s Accademia di Belle Arti, not out of the desire to study in such a prestigious institution, but because of the pragmatic need to obtain a legal residency permit. Xhafa’s persistence in somehow presenting the reality of immigrants in a different way was apparent in his installation Pleasure Of Flower (2000). In this work he transformed the coldness of a police station in the Belgian city of Gent into a warm and cozy living room. He brought in luxurious lamps and sofas, Persian carpets and a small library, placing them around the police station: Institutions exist to serve the people, and the artist’s desire (and ours) is for them to be warm and hospitable to all of us. Another representative work is Again and Again (2000), in which the Royal Philharmonic orchestra of Antwerp plays Mozart and Beethoven all wearing black terrorist masks. Prejudices against people wearing masks made the artist ask if the same people could make a cultural contribution. 4. Ali Hamadou is a gigantic five-meter sculpture of a Black businessman walking with a briefcase in the complete darkness of the large hall of Fondazione Teseco in Pisa. This work also deals with the issue of immigration and offers a possible solution to the problem of the aging of native European populations: immigration by so-called “third world countries” will inevitably lead them to become the new businessmen. Xhafa seems to insist that the Black businessman and his genuine-leather briefcase (and not as a salesman of copies of the same briefcases on the attractive Azur coast) is one possible future of Italy and Europe. The truly titanic size of this work and its unusual installation in a frightening environment make Ali Hamadou’s walk touchable, but at the same time unstoppable, gigantic but also pleasant. 5. Every day the TVs and newspapers are filled with images of post-Saddam Iraq — bodies and destroyed vehicles. The installation Untitled Sunrise of three exploded cars in the group show Hardcore at the beginning of the year in Palais de Tokyo in Paris looks into the distorting role of the media, and how journalists align their reports along emotional fronts, rather than constructing a broader analysis. Through performances, sculptures, photographs, videos, installations and drawings, Kosovo artist Sislej Xhafa gives social dilemmas a unique and provocative, sometimes even “illegal,” spin. He uses the mechanisms of a kind of political and cultural kitsch in order to make us more sensitive of the existence of circumstances and situations we are not always aware of. "

01.03.2003

Рекомендуемые статьи

|

|||||||||||||

Комментарии

Статья не была прокомментированаДобавить новый комментарий