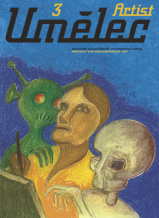

| Umělec magazine 2007/3 >> A CHARMING EXHIBITION, OR KASSEL OF 2007 | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

A CHARMING EXHIBITION, OR KASSEL OF 2007Umělec magazine 2007/301.03.2007 Marek Pokorný | review | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

As a world exhibition of contemporary art, the documenta of Kassel has two great advantages, at least as compared with other periodically organized exhibitions of a similar scope and impact. First, a five-year period, which elapses before the next exhibition is held, provides enough time to catch one’s breath, to perform research and to think; and second, the attention of the audience, critics as well as the nominated curators can focus on news concerning the development of the world art scene and its key problems from their own point of view. I have experienced the last three editions of the Kassel documenta personally and read about the others in catalogues and secondary sources. So far, I have always had the impression that I had seen a lot, learned a lot and that there’d still be a lot more to learn. The fact is, however, that I did not find the cold academic poise of French curator Cathrin David, which she chose for her otherwise magnificent examination of art in the globalization context, very appealing. It featured one slight imperfection: it failed to reflect the specific conditions under which it shows the engagement of art in the world’s political, social and economic matters; this is something that exhibitions of this particular type have been lacking since the 1980s, and will always lack. Okwui Enwezor, from Africa, offered an even broader panorama embracing art from all over the world with an intimate familiarity that no European view could attain, being so overdetermined by its own methodological problems; yet the scope of his discourse was perhaps even broader than the one of David (political philosophy, sociology, critical theory, and feminism were naturally and meaningfully accented by reflections of post-colonialism etc). Therefore, I perceive this year’s concept of the Kassel documenta, made by Roger N. Bruegel and Ruth Noack, as a quite logical answer that draws attention towards aesthetic qualities of a work of art and proposes to consider whether personal preferences and curator’s trust in a particular type of artistic statement can today play any part of the process of organizing such a large and closely watched exhibition. Seven years ago, Detail magazine published my review of an exhibition that had been organized by the present curators of the Kassel documenta for the Generalli Foundation in Vienna under a title Things we don’t understand. The review was called “…We Don’t Understand.” The project they worked on at that time was also characterized by a theme of aesthetic autonomy under circumstances in which general attention was focused on the current political position of an art work. The Benjamin-post-Adorno belief of Bruegel and Noack that maintaining a difference between art and politics has also become politicized has left me rather confounded; but that did not keep me from enjoying the exhibition. Although I did not understand the problem that they were referring to at that time, a simple comparison between the conceptions of Cathrin David and Okwui Enwezor with those of Roger N. Bruegel and Ruth Noack reveals the legitimacy of the authors of this year’s documenta. The politization of art has brought forward issues discussed in art using media that are, in a manner – often politically – thematized. Nevertheless, the political character of works of art as a representation of politics or political actions is neutralized by the politics itself, and the only way out is to try to reestablish and maintain distance from any kind of “aesthetic autonomy,” which itself renews and preserves the political character of art. That is a rather simplified explanation, yet the things we do not understand become a source of doubt, action, commitment, interest, and politics. At the same time, it is a principle that rescues the work of art. When we look back upon the exhibition of this year’s Venice Biennial entitled “Think with the Senses, Feel with the Mind” by Robert Storr, the imperative of the twelfth annual Kassel documenta becomes apparent. In Venice, I was constantly preoccupied, wondering why all the committed artists did not go and help the starving or assist in a hospice, or why they did not seek out full-time employment as welfare officers in ghettos; in Kassel, I tried only to figure out what their persistent message about the present world is, what acts their works should provoke me to do, and why they are so urgent. The twelfth documenta is a charming exhibition, extraordinary in its sensitive composition interconnecting all works without inducing their mutual elimination. The rhythm, the possibility of concentration as well as the ability to survey their interrelations (often intuitively established, yet strengthening the mutuality as well as the individuality of the exhibited works) – all of those aspects formed an exceptional experience. I haven’t experienced art in a similar manner for quite some time. The choice of the exhibited artists, which is usually one of the subjects of criticism, was not disconcerting. Others would do a different job. The important thing is that nothing was shaky. Should there have been more of Gerwald Rockenschaub or Peter Friedel? Who cares? The intention was not to observe proportions but to deliver the message which is obvious without the need to conform the works to this message or without reducing their individual character. But let me get back to the fact that there are many artists who were absent and that some of whom have been represented excessively. On one occasion Robert N. Bruegel pointed out that everyone has a limited capacity and is acquainted with only a part of the total of the world of art. Indeed, he is thoroughly familiar only with one portion; this is reflected in the background of their choice, and clearly forms a reliable basis. An exhibition is neither a jigsaw, nor a crossword puzzle. Whereas there were apparently no significant attempts to reflect on the entirety of Enwenzor’s documenta (2002) in the Czech media, as concerns the jubilee documenta by Cathrin David (1997), Jakub Vojvodík, a lecturer in Czech studies, attempted to come to grips with contemporary art using theories by Hans Sedlmayr, a figure in German art history had become somehow and unfortunately entangled with Nazism. His publication called “Loss of the Centre” can hardly represent a source upon which a positive attempt to get to understand the art of the past one hundred and fifty years could be based. During a period of culmination of conservative tendencies within Czech society, this criticism can be considered typical—as is the fact that there was no reaction. As regards the last edition of documenta, there were only two marginal comments, both of which also seem to be typical. In the Respekt weekly, Jan H. Vitvar presented mainly his own perplexity when judging the qualities of such a sophisticated project. The benefit of his text, however, was that he summed up the history of the exhibition and rather disproportionately pointed out the presence of three Czech artists (which by itself should have been published on the cover pages of dailies; a decent society would have published interviews with Běla Kolářová, Jiří Kovanda and Kateřina Šedá daily–even in tabloids). Although the author of the article forgot to remark that especially Běla Kolářová’s works had an extraordinary company (e.g. works by Mary Kelly and Zoe Leonard) and that the way of presenting their works was as impressive as it could possibly be. He provided a detailed account of the trouble Kateřina Šedá had with financing her project. Perhaps he misunderstood the author’s message or he does not know much about the organization of other exhibitions. Šedá struggled hard (without knowing the rules) and she managed to win. At other exhibitions she would not be able to find anyone who would be willing to discuss this matter with her. To attribute arbitrariness of curators to the documenta of Kassel and their present authors is far from appropriate. The “spec- ter” of a curator, which has been made up by Czech critics for reasons that tend to become more and more obscure, lives its own life and appears especially to those who have never been confronted with real ways of the world of art outside the Czech Republic, and probably only in their mirrors. Another example of a reaction, which is at home in the Czech Republic, is the recent moan by Giancarlo Politi from Italy who did not resist the temptation to use his e-mail circular to slander an “unappreciated artist from Vienna” who had been put in charge of this year’s edition of Kassel. Yes, I have seen the Praguebiennale 3 in Karlín.

Ai Weiwei Ai Weiwei’s Template (2007) sculpture encapsulates many of the themes that the Chinese artist is famous for exploring. By grafting together remnants of the past, namely old wooden windows with blocked panes and doors from demolished sites in China, Ai Weiwei’s sculpture probes our memory and asks us to expand our perception of the past by accepting these discarded scraps in their new form. The fragmented nature of the structure relates to the way our memories piece together stories to create a singular impression of the past that informs the way we perceive our existence. The disparate pieces jam together like an intricate puzzle that emerges from its flat outdoor setting. Standing tall, Template commands the attention of the viewer and invites them to explore. One is able to sit by the base of the sculpture, study it at a distance slightly removed, or move through it as if taking part in a ritual exchange. Weiwei’s sculpture possesses a solid presence, like a monumental building with all its parts locked into place. However, the artist has also achieved a sense of lightness and movement that allows the piece to seem suspended; the individual components sliding together and apart climbing towards one another to form a larger pattern. Captions of dokumenta artists prepared by Shaina Horowitz for Umělec Magazine. George Osodi Nigerian photojournalist George Osodi’s series entitled Oil Rich Niger Delta (2003-2007) delivers a sobering vision of life in the Niger Delta. Through Osodi’s lens we are offered a raw and immediate glimpse into the Niger Delta, a place which has been exploited for its oil since the 1950s. While Osodi’s compositions depict chaos and destruction he also presents us with the haunting beauty of the colorful landscape and the faces of people who have not surrendered to their tragedy. Action and resistance in the form of expression characterize the nature of Osodi’s work and are also foundational themes for many of the documenta 12 artists whose brand of passion and perseverance serve them well as they give form to previously overlooked realities. Juan Davila Juan Davila’s work splits apart simple notions of national identity and challenges dominant representations of history and belonging. He is not afraid to rupture our sense of continuity by provoking reexaminations of established ways of seeing. In order to do this Davila borrows elements of high European art like French salon style painting and blends in his own brand of pop-art and contemporary mass media references. Often his paintings look like traditional works that have been tampered with, their precious appearance intruded upon by raw versions of other stories that have yet to be presented to the public. These juxtapositions infuse his work with a politically charged edge as he negotiates the chasm between these different forms of expression to create something entirely personal. As he straddles the often complicated and ambiguous nature of his own identity, he was born in Chile and remains concerned with the problematic nature of Latin American politics of representation, but now resides in Australia, he performs a type of translation. He finds inspiration in the fragmented nature of modernity and his style matches this aim to interpret and personalize history, quilting together new stories with a distinctive and often perverse version of realism. Ferran Adriá For Ferran Adria food is art. Food is to be studied, deconstructed, reimagined, experienced, and ultimately internalized just as we are accustomed to doing with other media of art. We consume art and we consume food, but a meal dreamt up by Catalonian Ferran Adria is far from most culinary experiences. Adria is a culinary artist reinventing the experience of dining with signature 30 course meals. His process hinges on an incorporation of familiar ingredients in a completely new and innovative way. Challenging his customers’ palettes and satiating our ever increasing desire for something pure but innovative, exciting and previously unimagined, his plates look more like carefully crafted sculptures. Adria’s passion for experimentation and innovation are kept sleek and effective as his dishes adhere to a minimalist aesthetic. elBulli, Adria’s small restaurant in Cala Montjoi will serve as the exhibition space for his work featured in documenta 12. For the fifty lucky guests who will enter the Kassel site and be invited at random to dine in elBulli, Adria remains focused on the art of pleasing all of the senses through an elaborate culinary experience. Grete Stern Much like her work entitled Madi (fotomontage, 1947) that conveys an urban landscape seemingly devoid of human presence (it is as if the tools of industry exist as monuments, gargantuan toy blocks arranged and deserted) Grete Stern utilized the landscape of modernity to fit her own expression.. Stern, born in 1904, studied graphic design and photography under the guidance of Walter Peterhans at the Bauhaus in Dessau. Stern’s desire to connect to the conditions of modernity, as experienced in growing industrialized centers around Europe, led her to work with the photo montage technique. As a remarkably modern woman Stern also founded an advertising and photography studio in Berlin and worked as a freelance graphic designer and photographer in London before emigrating to Argentina in 1936. In her documenta 12 work, Madi, Stern inserts the letters M-A-D-I so that they appear like an advertisement in an expansive urban landscape. Madi was a group of artists whose work Stern had exhibited in her home but who enjoyed little public recognition. In this way Stern’s work is personal and purposeful as she uses the photograph as a platform to interject this group of artists into the public realm, actively redefining the cityscape with her own vision. Annie Pootogook Annie Pootogook’s work is informed by the landscape and drastic transformations that have defined her life in the Canadian Arctic settlement of Cape Dorset. The artist tells her stories with graphic images, first drawn in pencil then layered with ink and colored pencil, that illustrate the complicated and often bleak reality of inuit society. In her lifetime, Pootogook is 38 years old, the appearance of life in inuit society has changed drastically: in her drawings the long established problems of alcoholism and abuse collide with modernity, in the form of consumer goods, new technologies and access to media which has recently arrived in the artic north. Elements of the traditional landscape, such as a small hut in desolated rifts of snowy mountains and a curious polar bear now seem oddly displaced standing aside signs of modernity such as crumpled oil cans and flashing television sets. Pootogook has found a way to expand the tradition of illustrated storytelling in order to incorporate the particular reality of her own generation. Leon Ferrari Leon Ferrari’s series of works for documenta 12 convey an increasing sense of panic and disorder associated with the modern condition of urbanization. In Planta (ground plan, 1980), Passarela (Pedestrian Bridge, 1981), and Passarelas (Pedestrian Bridges, 1981) architectural-like systems twine together and overlap, pumping small uniform units through their bowels as if depicting the miserable fate of the individual in the ever-growing city. Ferrari lived in exile in San Paolo for many years after he was forced to desert his junta-ruled country in 1976, and this sense of turmoil and entrapment is evident in his works from this time. The urban plan as conceived by Ferrari is an intricate system of regulations that force swarms of individuals to move through a delineated space together. As the modulated units float deeper and deeper into a web of chaos it is obvious that the system itself is exerting the invincible pressure onto the individual, requiring it to conglomerate into the larger mass. Dias & Riedweg Notions of public and private, the distinction and consequent blurring between the two, are central to the Brazilian-Swiss duo of experimental artists Mauricio Dias and Walter Riedweg. Through the video installation Voracidad Maxima (Maximum Greed, 2003) Dias and Riedweg draw the audience into a position of consumption as they are forced to take an active role in choosing , via remote control, which video interviews they would like to view. The interviews take place between the artists and “chaperos,” male sex workers based in Barcelona. As the artist and interviewee tackle a range of issues the atmosphere is relaxed, as evident in the still image where the artist and interviewee’s head align horizontally as they lounge by the sea, a sheet of calm ocean waves stretching out behind them towards a blue horizon. Visually the two figures’ heads form one dsitinct shape, this blurring of identities is further complicated as the subject of the interview wears a rubber mask fashioned to look like the interviewing artist. Thus the artist literally envelops his subject, becoming both consumer and producer of truths. By inscribing his physical presence onto each chapero, men that hail from a diverse range of backgrounds, the artists collapse the distance between self and other complicating issues of identity as read in public and private contexts. Kerry James Marshall American artist Kerry James Marshall has set about to revise the history of western art in order to include a significant black presence. The flat quality of Marshall’s paintings deliver both the figures and their settings directly to the viewer, forcing one to consider the artist’s story. Marshall’s style often asks the viewer to occupy a space of discomfort as his figures are sometimes simplified types, skin almost ink black, posed against backgrounds like old famous European paintings or developing their own story line in pieces that use the paradigm of the comic. Marshall’s work forces one to recognize the reality of black identity, including the depiction of black sexuality in works such as Could This be Love (1992), as a way of making apparent how the canon of western art has previously attempted to erase the African-American presence. CK Rajan CK Rajan’s collages play upon the wild and extreme flood of images that bombard him in the rapid paced modernization of India. He snips and pastes together clips from newspapers and magazines, compressing space and time to reveal something about the quality of life in such an environment. In one of his works shown here a tanned arm juts out of a white skyscraper, as if the body is fighting against containment in the built environment, fighting to reclaim identity and a sense of connection to the surroundings as its fingers grasp at small trees growing below. Rajan’s other documenta 12 collage depicts a brutal fight: people jeer towards and away from each other swinging weapons and collapsing into a dilapidated building while a man dressed in white leaps and twists into the air. Rajan’s work made between 1992 and 1996 offers a different more confused and crowded emblem of modernity as compared with the work of Grete Stern decades before in Europe. Romuald Hazoume Romauld Hazoume cites Africa, specifically the rich history of Yoruban art and his personal connection to Vodun religion and tropical Catholicism as the main sources of his inspiration. In an effort to make a distinct identity for himself as an artist, one that counteracts the often collective focused efforts of African artists, Hazoume has helped to found the first museum for contemporary African art in Cotonou, Benin. In the past, recognition of individual African artists has been overlooked in favor of a more generalized impression of their aesthetic as a whole and a study that highlights the anthropologic value of their masks and other artistic objects. To better understand the history of these practices Romauld Hazoume began interpreting traditional Yoruba masks into his own distinctively contemporary versions. These so called “kaeletas” are made primarily from plastic cans, a ubiquitous waste product of modern society, and for Hazoume each mask is a specific character. Hazoume’s main contribution to Documenta 12 comes in the form of a large boat. The boat, made from 421 black oil cans, is perched against the background of an sun drenched, palm-tree filled beach as if contemplating a sea journey. We are left to wonder who is meant to travel on this vessel. Are the passengers choosing to leave a homeland or are they being forced to flee? Is their mission, on a boat made of leaky and discarded cans, doomed to fail or is the prospect of their mobility a form of freedom? Berlin Saray Albums (Diez Albums) It is believed that diplomat Heinrich Friedrich von Diez, the Prussian ambassador in Constantinople until 1790, compiled what are today known as the Diez Albums. The albums include paintings, sketches, calligraphies and engravings sourced from the late 13th to late 18th centuries collected from areas as wide ranging as Turkey, China, and Iran. Viewed in relation to one another the images become signs devoid of their original meaning and understood primarily by their visual appearance. The album format allows the viewer to become like a reader enthralled by the storytelling quality of the images. The works serve to preserve specific voices from the past, making significant and real their contributions to the lineage of art for future generations. We are able to covet and personalize our understanding of these cultures and their various forms of expression over the course of six centuries. As a collection of images the Diez albums perform a similar function as some of the other documenta 12 works that bring together disparate elements and personalized expressions of history to guide us towards a more complex and nuanced understanding of history and our present world.

01.03.2007

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

|

04.02.2020 10:17

Letošní 50. ročník Art Basel přilákal celkem 93 000 návštěvníků a sběratelů z 80 zemí světa. 290 prémiových galerií představilo umělecká díla od počátku 20. století až po současnost. Hlavní sektor přehlídky, tradičně v prvním patře výstavního prostoru, představil 232 předních galerií z celého světa nabízející umění nejvyšší kvality. Veletrh ukázal vzestupný trend prodeje prostřednictvím galerií jak soukromým sbírkám, tak i institucím. Kromě hlavního veletrhu stály za návštěvu i ty přidružené: Volta, Liste a Photo Basel, k tomu doprovodné programy a výstavy v místních institucích, které kvalitou daleko přesahují hranice města tj. Kunsthalle Basel, Kunstmuseum, Tinguely muzeum nebo Fondation Beyeler.

|

We Are Rising National Gallery For You! Go to Kyjov by Krásná Lípa no.37.

We Are Rising National Gallery For You! Go to Kyjov by Krásná Lípa no.37.

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment