| Umělec 2005/3 >> This Will Always Be Beautiful | Просмотр всех номеров | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

This Will Always Be BeautifulUmělec 2005/301.03.2005 Jiří Ptáček | review | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

Vladimír Skrepl, A. M. 180

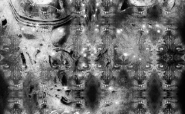

Prague, April 1 -15, 2005 “The independent creative and promotion collective,” A.M. 180 devotes itself to music production and also organizes art exhibitions, applying different rules for its different activities. It invites musicians from all over the world who know what DIY means and who are ready to accept lower fees than in the West. But in its gallery, in Prague’s Utopia club, they only exhibit artists of the “Czech-Slovak circle.” Despite all the enthusiasm that holds them together, the A.M. 180 collective realizes that everything must be paid out of their own pocket. And they understand well that exhibitions with a higher budget would soon empty this pocket. It is therefore surprising that the gallery’s program has been exceptional for so long. Since last winter there have been artists such as Marek Meduna, Matěj Smetana, Jiří Kovanda, Ivan Vosecký, Vladimír Skrepl, Milan Salák, and Jan Kotík. And all the above-mentioned names presented elaborated and outstanding projects. The local artists are simply happy to exhibit in the gallery which, for the youngest generation of artists is a kind of acid test. Anyone who does not pass the test can expect criticism close to home. In that environment it isn’t important that the exhibition does not receive much media coverage; word-of-mouth suffices. In the last two or three years word-of-mouth has had it that Vladimír Skrepl is not as successful as he used to be. That’s no surprise. Because one of the features of his artistic attitude is that he refutes himself from time to time, I was not entirely sure of the implications of these distinctions of “before” and “now.” I observed how perplexed the public was that he is devoted to painting and pictures. Some have taken this as an argument supporting their prognosis of a Czech pictorial revival (even though Skrepl hasn’t been appearing at recent painting exhibitions). Others have accused Skrepl of formalism, and some unspecified indebtedness to foreign influences. Such discussion generally remained in the intellectual backstage, and reflections of Skrepl’s output tended to be half-hearted, mostly because of critics’ fear of Skrepl. They know well that he dedicates a lot of time to monitoring art and its theory. There is a biased assumption that only an equally educated adversary can be a well-matched opponent in an intellectual game with him. I hold the view that Skrepl does not have such apprehensions and, on the contrary, see him as a semiologist of painting who strives to create communication pathways. That alone was a sufficient reason to go and see his exhibition at A.M. 180. It is Good to Soil the Painting It cannot be doubted that during the 1990s Skrepl was moving more freely among artistic media than today. He painted, drew and installed pictures and also made objects from textile or plastic. Yet after some important exhibitions in 2001 (in the Gallery of Václav Špála and Jelení Gallery) he focused on painting. Soon, he began to digress from the style that brought him his days in the sun. During my visits to his studio in 2003 and 04, I found out that his former free and innovative associative connecting of symbols had concluded. Skrepl began to analyze the composition of his paintings in detail, as if he wanted to stay undefeated by the art of painting. At one point he simulated expressive gestures as popular indicators of creative power, at another point he piled on ill-suited color combinations. Spray paint, which was the inspiring media for the first generation of the pop-culture, consumerist generation of painters (including Skrepl), kept reappearing on his canvasses. Yet it ceased to dominate the new pictures, and was rather lost in the sludge of impasto of various quality and origin. As if Skrepl wanted to say that if the historic references to gestures and painting in pictures cannot be avoided, there is nothing else to do but to soil both things properly. The subjects of his paintings came more out of tradition: still life, portraiture… If we compared this process to crossover in music, consider a sitar improvisation that was not followed by balalaika strumming, but each note was played on a different instrument. He did not hesitate to imitate an electric guitar with a balalaika and immediately after blow it like a trumpet. The only link to tradition was to be kept by the simple, classic genre: sometimes a waltz, sometimes a polka. Such paintings can make a grotesque impression. As long as we think that the aim is the sound of a sitar—or even a sitar waltz—this imitation will sound uninviting to us. We will recognize it only if we accept that staying on the boundary between several antagonistic, or not fully expressed intentions, is at the same time the aim. We might also see in it the core of the theory that Skrepl’s painting is not what it used to be. And perhaps it is even the quintessence of the accusations of formalism and obsession to remain the author of the paintings. Nevertheless, as I shall attempt to prove in the case of the exhibition in the A.M. 180 Gallery, therein also lies Skrepl’s fundamental role in the transformation of the Czech attitude to the art of painting. A Riot of Textures and the Moment of Satiation As with most European countries, the shape of Czech art history has been determined by the role of painting. But this is not always for the same reasons. To begin with, the cultural and political events of the second half of the twentieth century suppressed the development of different artistic forms in different regions. Tracing the departures from the central cultural ideologies—that have intensified in recent years—is often associated with the rejection of painting and pictures as the highest bastion of the past. This paradoxically evokes an undesirable reaction from the side of painters. Some isolate themselves from society and speak of themselves with the unwavering certainty that they have been chosen to see beyond trends and fashions. The others focus on the re-establishment of the spectacular qualities of painting, and sink into believing the false idea that painting can be developed without any deeper questioning about what context we are entering by using it today. Skrepl’s pictures presented at A.M. 180 look spontaneous, uncontrolled and wild. Paints have been sprayed on the canvas with a “Pollock-like” detachment. Some formats are nearly covered with a thick layer of color impasto as if Skrepl ceased swirling the paintbrushes over the canvas only when the original paints were blended into a uniform shade of brown— child’s play with Plasticine. Yet the dilettantism and also the simple effect have their important consequences. Skrepl’s paintings have been going against the traditional craft of painting for years, though this time they are facing the topic of the social role of painting, picture and art history perhaps even more than ever. Dripping, a tendency to monochrome “colorlessness” and “texture” are important tendencies of the final phase of modernism and an aspect of the period’s ideas about the autonomy of the art of painting. In the Czech Republic these culminated with structural abstraction during the 1960s. Artists like Robert Piesen and Mikoláš Medek are still favored by the curators of large gallery expositions, visitors and Sunday painters. They are considered to be the foundation stones of the national painting tradition. There are only occasional polemics about the extent to which this is a consequence of the cultural-political mythologization (Jiří and Jana Ševčík, Milan Knížák). So far they have not touched fertile ground. It is not surprising that structural abstraction sits in the artists’ stomachs like a hard-to-digest stone. The refusal of its aesthetic premises is a widespread attitude. Not with Skrepl. Several paintings for the A.M. 180 show “innovate” structural painting by using “today’s” materials (glitter) and pop-culture signs (the acidic smiley face). Thanks to his informal morphology, they mainly comment on the relationship between art history and the topicality of style like other pictures with which Skrepl has been filling up his studio for two years. Skrepl intervenes where he feels the absence of a preceding satiation. He may not even care that the relevancy of such gestures may fade with time. The satiation with certain types of pictures in different intervals dies out and moves elsewhere. And Skrepl moves along with its shift. Shouldn’t we, for this reason, regard Skrepl’s pictures as political acts? A Lonely Runner and an Unwavering Opponent In this sense we would hardly find an equal partner in our country. Sometimes Petr Písařík, David Adamec, Josef Bolf come closer to him, in his happier moments also Jakub Špaňhel. However, these approximations are brief. With Skrepl, it is a systemic search for places where the aesthetic censure is in force at the moment (even if unforced). The closed cycle in A.M. 180 seems to be showing that the impulse for painting does not have to be so much a “shift” from the standpoint of painting, as a sounding of what is just “now” socially undesirable and thus worthy of subversion. What remains unexplored is for example the possibility to compare Skreplîs paintings with the older works of Jiří Georg Dokoupil. Although Dokoupil does not exploit the Czech painting doctrines, we could find an adequate “Skrepl-like” pendant in his works. Only, Czech culture would have to include its famous emigrant in its local activities. And that is, for incomprehensible reasons, not happening. If that ever happens, perhaps it will come out that Skrepl is not a lonely long-distance runner who is feeling worse than before, but a very good runner on the field of reflection on painting in its immediate aesthetic limits. So there are possible solutions.

01.03.2005

Рекомендуемые статьи

|

|||||||||||||

Комментарии

Статья не была прокомментированаДобавить новый комментарий