| Umělec 2005/3 >> In expectation of reloading: Ukrainian Media art | Просмотр всех номеров | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

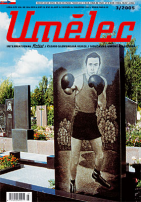

In expectation of reloading: Ukrainian Media artUmělec 2005/301.03.2005 Jekaterina Stukalova | Ukraine | en cs de es |

|||||||||||||

|

Paraphrasing Voltaire, one could say that if contemporary art did not exist in Ukraine, it would be necessary to invent it. Fortunately, contemporary art does exist in Ukraine. But the mere fact of its existence seems increasingly paradoxical: contemporary art depends directly on the degree of development of art infrastructure and cultural policy of the state. For almost twenty years, this infrastructure failed to be created, and any shy sprouts of the 1990s—funds, festivals and galleries—either perished on a terrain poorly fertilized with money or continued a slow vegetable life. In this system there is no room for innovation, non-trivial ideas, and original gestures; in today’s Ukraine, there is no room for such principles of cultural policy that would be adequate for the time to some extent.

So it is curious that at least one contemporary genre, media art, can be included among made-up Ukranian ideas that have been artificially cultivated and realized regardless of the existing realities. Most media artworks involve the participation of the usual actors of the current art scene in their creation and presentation, and involvement of industrial and technological resources. Modern artists who work with painting, installation and performance may grumble about the absence of support from the state and endowments, and the insufficient development of an art market or the lack infrastructure for expositions. Nevertheless, they realize their art projects even in the least favorable conditions. The absence of such support for media art has put its very existence at issue. Media artists are confined to the amateur framework of the Internet and flash animation, or purely commercial publicity and mass media. In Western European countries, Japan and the US, high tech corporations are open for mutually beneficial collaboration with artists. As artists and creators headily step down from their pedestal and evolve from demiurges and radicals into art directors and developers of special effects, this collaboration is becoming one of the main forms of communication of artists with the community. Such artists are regarded as specialists able to enrich an otherwise soulless technology with non-standard visions, and the construction of original creative models. Institutions that exhibit media art give instant publicity to new technologies among a growing number of potential users. Media art festivals, the main venues of its popularization, evolved mainly from video art festivals, themselves successors of documentary festivals. With that in mind, this evolution not only enabled the expansion of engaged media and presentation models, but also brought intellectuals and professionals out of their secluded worlds to the authentic mass public. Unfortunately, all this is far from the Ukrainian situation. Here, media art has absolutely different roots, a different trajectory of development. As such, it is hard to predict the future for Ukrainian media art. I deliberately avoided analyzing video art that used to be the first big media intervention of contemporary art but has recently separated into an individual and in many respects autonomous genre. It is no surprise that the history of video art in Ukraine is twice as long as the history of digital media. The statement saying that a painter or performance-artist can create independently of supply and demand applies to video artists as well; domestic and professional video equipment have become widely available during the last fifteen years. Computers are widespread as well (at least on the users’ level). Never-theless, an amateur media art trend that includes a multiplicity of phenomena– from Demoscene to flash animation, from ASCII- and ANSI-art to virtual communities–failed to spread in Ukraine for different reasons. It did not develop into a subculture, a community of media activists able to replenish Ukrainian media art with ideas and forms of “new folk arts” as has happened in many Western countries. As early as the second half of the 1990s, the youngest generation of Ukrainian artists in the shadow of a conservative artistic community was clearly taken in by the new means of expression. The Info Media Bank program initiated by curator Natalia Manzhali in 1997, brought such fruitful results. Through that, a number of master classes on modern technologies for artists were organized with media laboratories at the Kiev Contemporary Art Center (CAC) (formerly the Soros CAC) turned out to be a significant creative stimulus. Opened to help artists master practical skills of working on the Internet and the basics of programming and animation, these master classes were attended by a circle of artists who constitute the base of Ukrainian media art today: Margarita Zinets, Alexander Vereshchak, Gleb Katchuk, Olga Kashimbekova, Ivan Tsyupka, and Natalia Golibroda. The artists who first appeared on the art scene in the late 1980s–Ilya Isupov, Ilya Chichkan, Alexander Gnilitsky, Oxana Chepelik, Vasily Tsagolov–used the media laboratory’s resources in their new projects. Ilya Isupov’s Zhaga project (Interactive Object of Desires, 1998) is symptomatic as one of the first products realized in the media laboratory. Isupov ably used his graphic works and paintings to create a breathtaking sight in which citations from paintings were involved in a series of transformations. Other than that it was the most successful combination of resources of new technologies–morphing, animation, and electronic music—with a traditional picture technique, Zhaga introduced a new trend in the presentation of contemporary art. The project was presented in an internet café on a screen and several dozen computer monitors. A musical leitmotif, written especially for the project, was provided by a DJ. After that tour de force, presentations of media art projects became a more wide-spread form in Ukraine outside galleries and show-rooms, and instead were accompanied by parties and for large audiences who would not otherwise attend exhibitions. By 2000, the Info Media Bank program was transformed into the Kiev International Media Art Festival (KIMAF) and was conducted annually from 2000 to 2002. It included master classes, exhibitions, presentations, computer animation shows, electronic music concerts, performances, and parties. In addition to presenting the works by famous international artists to Ukrainian viewers–Pierrick Sorin, Crista Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau, Cammile Uttreback and Romy Achituv, Hiroshi Matoba, Gina Czarnecki, Mike Stubbs, Alba d’Urbano, Tobias Berndstrup, Palle Torsson–the Festival showed, and even produced and financed projects by Ukrainian artists. The majority of important works of Ukrainian media art were realized with KIMAF’s support or were associated with KIMAF programs. In 2000, the Festival hosted the first Ukrainian interactive installation, by Ivan Tsypka and Natalia Golibroda, Come to Me. The artists selected seductiveness as a subject and the seeming nearness of a teasing image on a screen that in reality transforms to become inaccessible and phantom. A seminude girl on a screen would wave to viewers, but disappear as they’d approach the image. As viewers would move away, she’d appear again and summon back those who’d sought a closer look. A similar theme was presented in Olga Kashim-bekova’s Antikaraoke (2001), in which a viewer who begins to sing can see a girl taking a shower. This work is a part of a larger series of the same name that Olga Kashimbekova has worked on for several years in partnership with her co-artist Gleb Katchuk. Unfortunately, Katchuk did not finish his project Karmageddon-Karaoke that was to be a pirated version of a popular computer game with a soundtrack made from popular music with text added to its usual interface. The speed of music and text reproduction would have depended on the velocity of a virtual car, driven by a game player, that would have complicated the process, but would have added some humane element to this “free-wheeling, fun and totally disgusting game.” The interactive installation by Alexander Vereshchak and Margarita Zinets, at the Festival in 2002, made no attempt to flirt with the public and did not try to seduce the viewer with the amenities of the virtual world. Instead, installation characters were stout middle–aged men presented life–size on a screen with their backs to the spectator. As soon as a viewer uttered anything one of the men turned around and repeated the same comment, using a comic intonation or ridiculous timbre. As often happens in media art no particular conceptual depth was applied to such works. They were exercises, experiments with technology; their visual interface was an attraction for viewers, a button that started the interaction process. However, whereas the characters in the earlier works would lure the viewer, Vereshchak and Zinets’ virtual men were rather scornful towards the reality on the viewer’s side of the screen. One more obvious trend in Ukrainian media art stands in sharp contrast to the tendencies of high tech and complex programming use. This application is not of the new but old, albeit marginalized visual techniques and media. This is particularly typical of Alexander Gnilitsky’s works, and a group of artists and musicians called the Institution of Unstable Thoughts which, in addition to Gnilitsky, includes Lesia Zayats, DJ DerBastler and Ksenia Gnilitskaya. Gnilitsky’s creative arsenal includes mechanical objects (natural to ultimate models of symbolic Ukrainian reality as a begging old woman or a coal miner on strike who casts his helmet away); a special type of phytodesign (sculptural phalluses that sprout with young grass in the course of exhibitions); mirror optical effects a la baroque. Gnilitsky’s works made for KIMAF reflected his ironic attitude towards the overall ecstasies over the new technology; with anthropological thoroughness, he simultaneously continued uncovering marginal layers of visual techniques of the past. In 2000, when Ukrainian artists’ passion for huge video projection was at its peak, Gnilitsky exhibited a bulky construction as large as a small house, but whose end product was a projection merely five centimeters in diameter, achieved using a camera obscura. Since 2002, the Institution of Unstable Thoughts has been modernizing their Visual Vinyl project, in which an impressive animation is created in a real-time operation mode using no computer technology whatsoever, but with a zoe-trope and simple lighting and video equipment. This tendency in Ukrainian media art can also be identified in Ivan Tsyupka’s Noise (2002). The project uses an optical “magic-eye” effect formerly a source of inspiration for Surrealists before becoming kitsch. In printouts that simulated the TV “noise” that is seen on the screen when it’s not broadcasting, the viewer who concentrated hard enough could discern three-dimensional pictures. If it is true that such TV noise is energy transmission that has clouded cosmic space since the Big Bang, then the images that appear in the printouts belong to supernatural spheres. Although rather speculative, the artist’s statement encouraged viewers to meditate in front of visually inexpressive pictures for a long time. Dmitry Dyulfan, an artist from Odessa who mainly works with light, incorporating neon lamps with multiple-colored lights in his performances, is also close to the “artesian” tendency cultivated by Gnilitsky. In Dyulfan’s works, neon light, a form traditionally associated with coldness a la Dan Flavin, comes across in a completely new way – exaggeratedly psychedelic, anti-industrial, and informally warm. This brief excursion into the history of Ukrainian media art suggests a possible forecast for its future. Unfortunately it is vague. Having lived on sporadic grants from different institutions and received no systematic financial support even from the state, the KIMAF could not endure the closure of cultural programs by big Ukrainian funds, and stopped two years ago. The Dreamcatcher Video Art Festival shared its fate. The CAC Media laboratory was closed even earlier due to the absence of financing too. With no stimulus to create new projects for big exhibitions and festivals, the associated artists departed for advertising agencies, television, or opted for foreign internships instead of trudging in their thankless homeland. It looks as if Ukrainian media art needs to be “invented” again or, at least, “reloaded” with additional functions. In this brief review, I would not like to overlook another trend in Ukrainian contemporary art. This trend does not operate with new technology, but scrutinizes the role in contemporary culture of media and, in particular, mass media and communication channels. Active use of mass media stamps and patterns was typical for a number of video works by Odessa artists Miroslav Kulchitsky and Vadim Cherosky in the second half of 1990s including Screen Copy, Highway Nyman and New York, New York. The artists would use appropriate well-known video fragments, and mix high culture with low (a soundtrack by Michael Nyman applied to a video fragment from Terminator). In addition, they’d bring to the forefront minor parts of videos such as subtitles and poeticize the shady aesthetics of pirate video such as low image quality and bad dubbing. In doing so, they outstandingly carried traditional visual and medial codes to an absurdity. Similarly, the works of Vasily Tsagolov, an artist who works in the spirit of conceptualism and actionism of the 1970s, are even more interesting. In the beginning of the 1990s, his paintings, actions, installations, and photos were apparently inspired by the trash aesthetics of pirate video, provincial TV and cheap series. By the mid- and late 1990s, the aesthetics of crime and violence—through which the motif of a comfortless though outwardly sparkling world peeped out—became the key point of his works. The appearance of the obsessive subject of terrorism as the ultimate and absurd fear of otherness is no surprise. Tsagolov’s press release for his Hard Television project best defined the role of mass media in the life of today’s individual. Tsagolov said, “In the mediacratic era, the present existential maxim, ‘to be is to be in the world,’ will be replaced with a new maxim, ‘to be is to be on the air.’ Existence will lose its ontological essence and clarity, and become a technical problem. To prove their authenticity people will have to appeal to TV stations and studios. Television will cancel philosophy but will appropriate its metaphysical functions and will decide who and what will be allowed to take place in TV life.” A series of actions related to this conception (such as the artist’s offering himself for sale during a TV auction; public refusal to continue art work and reading out a respective manifesto; ‘reanimation’ of the artist in a hospital) showed the artist’s self-sacrifice but looked like a baseless image that illustrated a beautiful conception. It is possible that Tsagolov’s rapt attention to television was somewhat premature and his conclusions about the mass media’s role in the life of average Ukrainian citizens were a forecast but not a diagnosis. The Orange Revolution resulted in the transformation of reality into decorations for a big TV reality show for two long months. Both major state institutions: The Supreme Rada (Council) and the Supreme Court, and city streets became studios. Key state figures and anyone who would come to the square during the days of the revolution could become a personage. Those days, TV ratings beat record figures previously made by New Year shows and on holidays. The society “migrated to television” as if confirming Tsagolov’s ten year old prophecy. How will Ukrainian art react to this new media concern? The issue remains open, but the “New Year’s card,” created without-delay by Ilya Isupov, shows that Ukrainian artists are not going to give up their ironic and sometimes sarcastic distance from ideological and political dogmas.

01.03.2005

Рекомендуемые статьи

|

|||||||||||||

Комментарии

Статья не была прокомментированаДобавить новый комментарий