| Umělec magazine 2007/1 >> Trekhprudny: Time to Ask Naive Questions | List of all editions. | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Trekhprudny: Time to Ask Naive QuestionsUmělec magazine 2007/101.01.2007 Andrej Kovaljev | commentary | en cs de ru |

|||||||||||||

|

On September 5, 1991, the Moscow public attended an opening of a new gallery. However, upon arriving at the attic of a house on Trekhprudny Lane, they saw neither paintings nor installations; they found two homeless people instead. Those typical representatives of the homeless class were busy with their usual affairs: drinking cheap wine, swearing, sucking on stinking cigarette-butts, paying no attention to the public. Organized by Konstantin Reunov and Avdey Ter-Oganian, that act, entitled Mercy opened one of the most important projects of the 1990s, the place known as the Gallery on Trekhprudny Lane.

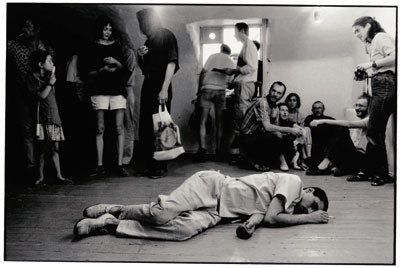

The brilliant Trekhprudny era began in 1990, when artists Valery Koshlyakov and Avdey Ter-Oganian semi-legally moved into an empty flat in a house at the corner of Yuzhinsky and Trekhprudny Lanes in the very center of Moscow. As the other inhabitants in the building moved out over time, the apartments became empty, and gradually, a real settlement was formed by Vladimir Dubosarsky, Pavel Aksenov, Ilya Kitup, Alexander Sigutin, Viktor Kasianov, Alexander Kharchenko, Konstantin Reunov, Oleg Golosiy, Oleg Tistol, and others. Included among the flats that the art squatters managed to occupy was a vast 36 square meter attic. With no right angle and a strange ceiling, the room was rather odd; but the artists decided to create a gallery in it and to conduct exhibitions and actions there every Thursday. During two exhibition seasons from September 1991 to May 1993, 87 exhibitions took place on Trekhprudny; another seven exhibitions as part of a gallery program were organized elsewhere. The Trekhprudny artists’ very first action established the new institution squarely as an independent artist-run space. However, the very name Gallery, adopted for this project, carried an element of ironic distance from that endless apologia of the art market to which the Moscow art community had been devoted. It was assumed that the art market was contemporary art’s singular driving force. As such, an artist would have to devote all their moral and physical strength to exhibit in order to burst forth from the unknown into the forefronts of the social scene. Hence, any level of publicity first implied a public ready to purchase individual pieces. However, no art was sold on Trekhprudny Lane; moreover, the Mercy action was an absolutely clear and pure representation of an artistic gesture detached from the production and distribution of art as an article of trade. This is why the refusal to “show up” in the market appeared as a polemical gesture in the midst of the monetary hysteria of the perestroika period—a time when the art world viewed trade in art as a supreme social and even ethical achievement. The art market, traditionally tailored for Western buyers, had fallen into decay by that time. As the Russian Wave associated with Gorbachev’s perestroika had finished, the thematic Mercy action stood in harsh contrast to the past state of affairs when light-weight cynical soc art — that used the prostrate Red Empire as its central subject —was most valued. Ter-Oganian and Reunov clearly and firmly announced that they did not want to deal with this mythology but wished instead to work with the real problems of society. Unfortunately, artists responding to present-day problems using their bold subject matter gradually receded into the background. Among the actions of this kind, one performance by Dmitry Gutov might be mentioned. During the action entitled, Small Items of Our Life the artist’s brother appeared as a stereotypical bank-clerk selling small copper coins by weight. At that time inflation was rampant in Russia and “change” was purely symbolic. But the crucial point of Trekhprudny Gallery’s aesthetic program was art, as such, and the conditions of its existence and realization. The gallery’s exhibitions and actions constituted a series of thoroughly adjusted, yet rather naive queries into the role of an artist’s personality in the art process, the meaning of institution, and the role of the public and press. Take, for instance, a real wedding celebrated in the Gallery’s space (an action by Yuri Babich). Would that be considered an artistic event or just an everyday occurrence? Or, what should one think about inviting gallery viewers to get in a bus and to go for an excursion through the city (The Whole of Moscow by Gormatyuk, Dubosarsky, Ter-Oganian). The Gallery’s life, just shortly after its enthusiastic opening that established it as presenting something new, on closer examination appeared to be presenting little more than pure routine. And one day, the public only finds an inscription As Always in the gallery (Viktor Kasianov). (In one more case, for which the invitation read, “Beware! Wet Paint!,” a wall was evenly painted a very bold color (Alexander Sigutin).) New art projects in Russia aimed to materialize abstract ideas in concrete forms. The Trekhprudny artists invested a lot of effort towards their subtle and ironic deconstructions that could carry those abstractions to absurd extremes. One unique aspect of the gallery was its critique of contemporary art institutions, in which they would use the public itself as a component of the art to allow phenomenon to be created. Alexander Sigutin (Demi-Season Exhibition) nailed 36 hooks into the wall and invited all who came to hang up their coats. As people departing would take their jackets and coats with them, the “picture” would continuously change and modify. Upon the departure of the last spectator, the exhibition ceased to exist. The public of exhibitions and actions is not a featureless crowd that came for the sake of the tusovka. Each viewer arrives at their own opinion and the sum of all those opinions becomes a part of the object of art, and often cardinally changes the initial conception. Alexander Kharchenko decided to materialize this phenomenon in his action entitled Sorting out One’s Relationship Using Weapons. He constructed an ordinary shooting gallery within the art gallery and collected the works of his friends-artists which they considered the most important, and used them for target-practice. Trekhprudny leader Avdey Ter-Oganian was the most radical as he offered to shoot at his own portrait, which then became the favorite target for the majority of the participants. Serious competition naturally existed within the group. But the various levels and degrees are elusive; Alexander Kharchenko created tangible measures for the descriptions of “big artist” and “biggest critic” by having all the artists measure their height and all the critics weigh themselves. I am proud to report that I, Andrey Kovalev, writing for the Independent Newspaper, was the heaviest. As a result, I called into question if I could remain far enough away from object of art to keep my partiality, as I had become the object. Nevertheless, as a result of this adroit and child-like operation I received the flattering status of the “biggest critic.” Our own techniques of critique were even used to help actions materialize. For the action entitled Form and Content (Reunov and Ter-Oganian), each artist brought a bottle of spirits with a hand-made label. These art objects were offered for expert examination by the art critics, who revealed that content was of no importance, as the form in art is above all. Ter-Oganian again gave the most radical answer having offered two absolutely identical bottles with vodka without labels, and noted that in contemporary art the form of work can also be absolutely empty as in Black Square by Kazimir Malevich. Genius of Place and Place of Genius In that collective carnival, all possible metaphysics related to the production, understanding, and dissemination of art were reduced to a maximally simple and often foolish act. As a matter of fact, the entire radicalism of Trekhprudny Gallery’s strategy was a reduction – all social, philosophical, and difficulties of their world-view were represented as a sum of simple and pleasant actions. For the action entitled, Sea of Vodka (Aksenov, Reunov and Ter-Oganian), the magnificent painter Valery Koshlyakov painted a splendid wave on one of the Gallery’s walls, in front of which was placed a table with cups of vodka. As a result, vernissage haunters felt seasick and realized the real essence of fine art while feeling as if they were themselves within the painting. In spite of the simplicity and brutality of the action, it concerned such important issues as perception and apperception, i.e. the ability to perceive works of art. Broadly speaking, the problems with alcohol played an important role in Trekhprudny’s actions. To some extent it was due to the analytical atmosphere of the place, where an investigation of the essence of art occurred, in a squat, a commune in which artists lived and worked. Traditional life style was implanted in the body of the art projects. Playing with the theme of alcohol began in 1991 at Trade-Exhibition organized by Konstantin Reunov and Avdei Ter-Oganian in Peresvetov Lane. It was very simple: about thirty boxes of cheap wine were piled in the gallery. A social witticism first emerged from the name of the action – the era was filled with such odd concepts such as commercial bank. The name Trade-Exhibition referred to the market hysteria that surrounded Russian society at that time. Such proud subtitles usually accompanied the most absurd undertakings in the commercial art sphere. Of course, the “exhibition” was a great success with surrounding inhabitants. Thus, the slogans of the Russian avant-garde —“Art for the People” and “Art into the Masses” —were easily realized. As a matter of fact, it was a very rough parody of a possible way in which art can dissolve in the midst of life. In this use of alcohol as art object and subject, some may refer to the stereotype of Russian hard drinking and hypertrophied attention to specific regional sign systems. On the other hand, there are the manipulations with alcohol in the manner of disputes between Russian Slavophiles and Westernizers of the 19th century concerning the Eastern "natural" tradition opposed to the "unnatural" Western tradition of drug use, which had a significant impact on post-war art. Besides, the use of spirits is an important factor in the life of Russian artists. Profane things are implanted in art on Trekhprudny and vice versa, art dissolves in profane surroundings. However, some actions were particularly original. For Against Monopoly, an action by Mikhail Bode, fresh home-brew was made in the Gallery. The action referred not only to a state monopoly in alcohol manufacture, but also to the aesthetic monopolism of a totalitarian state. Undoubtedly, such an analytical approach to the essential problems of functioning can be regarded as an ideal illustration of relational aesthetics, a concept introduced by French theorist and curator Nicolas Bourriaud in the mid-90s. World of Art The most famous action on Trekhprudny was the performance entitled Towards the Object. The public watched Ter-Oganian drinking vodka glass by glass and gradually turning from immortal creator of values into the object, which picturesquely settled on the Gallery’s floor. The matter, however, did not concern the traditional drunkenness of an artist who is entitled to irresponsibility and abruptness, but the very essence of art, the relation of subject (creator) and object, i.e. the work of art. Simulated naivety typical of the Trekhprudny aesthetics rendered senseless the suppositions which always chase Russian artists; accusations of being secondary are automatically remitted. The distinction between an artist’s real personality and the virtual body of their personage is always elusive. In the Soviet period, Ilya Kabakov, creator of the personageness concept, used to be a prosperous graphic artist and head of the organizers of children’s book designers. However, like Ter-Oganian would later, he spoke on behalf of an alter ego, a little Ilyusha Kabakov, who was suffering in a goddamned communal apartment. Ter-Oganian had a problem of personal accountability between artist and personage. The body of a dead drunk artist represented as an art object reveals the fact that the real Avdey Ter-Oganian had serious problems with alcohol. At present, Avdey has overcome these problems and doesn’t drink anymore. In order to represent a remake of the action in Berlin he had to enlist the help of a German artist. Following the instructions of Ter-Oganian, the artist came intoxicated to the vernissage, then drank vodka provided by Ter-Oganian. And, in accordance with his instruction, fell down dead drunk and turned into the object. We Are Not Local However, the basic aesthetic task of Trekhprudny artists was not to experiment with the structures of contemporary art, but to finish the postulates of modernism by creating classics beyond comprehension. It’s become the custom that art revolutions in Russia are made by provincials, who take a run so fast in their wish to blend in with the mainstream as successfully as Malevich or Tatlin. However, the artist does their best to hide the fact that he used to be a naive man, who devoutly took the heights of world culture by storm. Trekhprudny artists’ radicalism was in their determination for bringing that naive and ingenious personage to the forefront instead. That simple man who asked ridiculous questions about the meaning of art was in a way a response to Moscow conceptualism’s aesthetics, which meant maximal esotery of the artist’s views. In that system an artist had the whole of knowledge of art development in the 20th century. Naturally, that only was a facade as Moscow artists had only very vague ideas of the global art process. And they did not have any real knowledge of the subject, which sly provincials from Rostov had. The installation entitled Not a Fountain featured a working urinal; copies of an engraving showing “real” Roman fountains were hung on the walls. Besides being a very artless pun (“not a fountain” colloq. “not so good”), the action referred to Fountain, a classic 20th century work by Marcel Duchamp – an ordinary urinal offered to the exhibition committee of the New York Armory Show in 1917 as a work of art. So, that comical icon of modernism was dethroned in an appropriately comical manner: the public received beer in abundance and the toilet in the Gallery was closed. The public, hence, was made to use the urinal. The maximum epatage allowable in Trekhprudny’s aesthetic program was established in that easy and unobtrusive game with the viewers. Avdey Ter-Oganian personally implemented the program and was an creator of Not a Fountain. After Ter-Oganian’s departure for London in 1992, Konstantin Reunov became curator of the gallery and aimed to achieve simplicity and clearness in all of the gallery’s actions. These aesthetics were in serious contradiction to the postulates of Moscow conceptualism, according to which one had to achieve maximum intellectual esotery. However, the real conflict took place in the social, not the aesthetic sphere. “Poor” aesthetics of Trekhprudny artists came into conflict with the aspirations of “new Russians” to achieve a bloated level of respectability, from which any possibility of institutional criticism was impossible. Vladimir Dubosarsky who began to work in Trekhprudny, i.e. under direct influence of Avdey Ter-Oganian, said in one interview, “On Trekhprudny, a general style was present, which included: easiness of expression, quickness of fulfillment, cheapness, and so on. However, a feeling gradually appeared that we had to look for something new and more coincident with our brutal and aggressive time, which came to take perestroika’s place. Our Dadaist, anarchical, playing works were extremely fragile, vulnerable – if a critic does not write about them, nor publishes their photos in a magazine, then, nothing will remain of them, as if they never existed.” In 1993, when Trekhprudny’s era finished, a new period started, in which radical artists stepped outside of their world and got in direct contact with society. However, the ideologist and founder of Trekhprudny Gallery Avdey Ter-Oganian took almost no part in that new phase. He continued his experiments in relational aesthetics and in 1996 he created the Avant-Garde School, which some young friends of his son David joined. The group became noticeable in 1998, when they took an active part in the action Barricade on Nikitskaya. Along with Anatoly Osmolovsky and others, a street leading to the Kremlin was barricaded in honor of the events of May 1968. The next public action of the Avant-Garde School became an indicator of the almost pathological changes in Russian society. In 1999, after the action Young Atheist during the Art Arena Fair, Avdey Ter-Oganian underwent persecution from the Prosecutor’s Office and, as a result, had to emigrate to the Czech Republic. Initially, the action was not against religion, even though it consisted of chopping cheap orthodox icons with an ax. Instead, it aimed to demonstrate the definitive death of modernism, whose adherents always had to overthrow the authorities and ruin spiritual values. As a result, Ter-Oganian practically disappeared from the Moscow art scene; he spent several years in a Czech transit camp and then settled in Prague. At present, he resides in Berlin and cannot return to Russia. Lately, he has transferred his Avant-Garde School to Live Journal and has found many new disciples. http://teroganian.livejournal.com/

01.01.2007

Recommended articles

|

|||||||||||||

Comments

There are currently no comments.Add new comment